Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Gift of Chana (Livia Koralek) Spiegel, Bnei Brak, Israel

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Gift of Chana (Livia Koralek) Spiegel, Bnei Brak, Israel

Yad Vashem Photo Archive, 77991

In the third blog of this series, we examine how religious and communal leaders encouraged their dispirited and desperate congregations through ancient words of hope and faith in better times ahead. In so doing, they drew on the tradition of the midrashic form of biblical interpretation, making connections between new realities and ancient biblical texts.

The existential challenges posed by some of the traditional texts can especially be seen in sermons that were given around the High Holydays, times of repentance that are traditionally associated with Divine judgement and forgiveness.

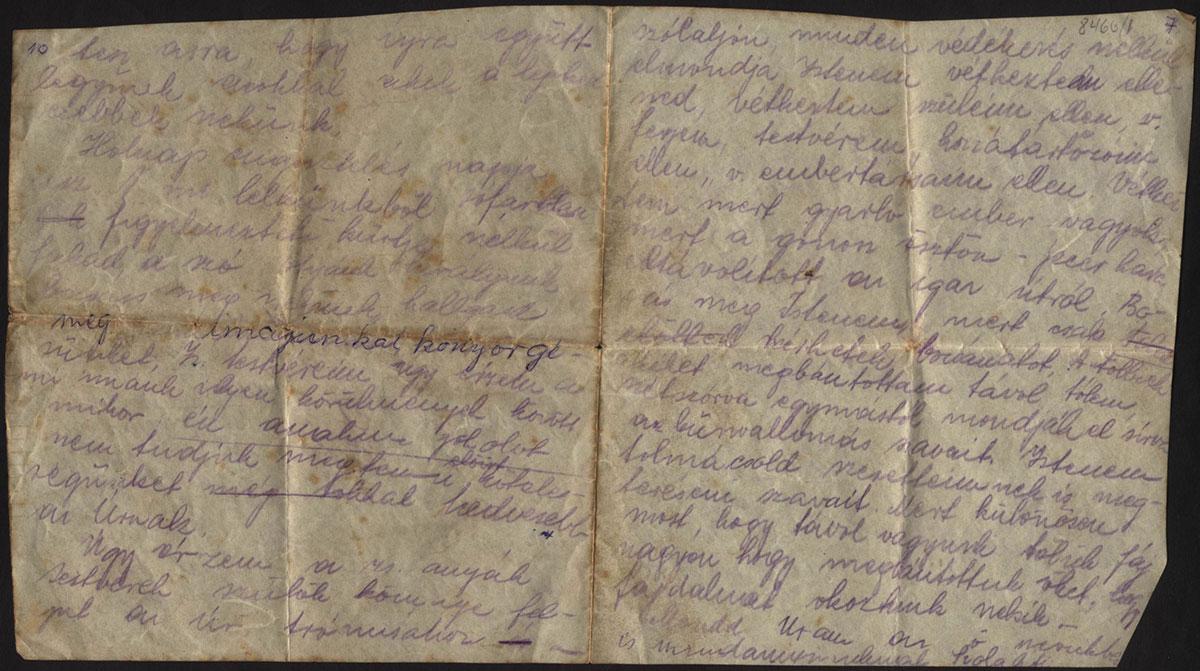

Addressing her fellow inmates in the Parschnitz camp on the eve of Yom Kippur 1944, Livia Koralek presented them with a challenge to preserve their humanity in their dealings with one another. She closed her sermon with words of comfort taken from the Slikhot prayers recited on Yom Kippur:

“I feel that God will hear our prayers, wipe the tears from our eyes, and answer us with the words from the prayer service: 'I have forgiven you.'”

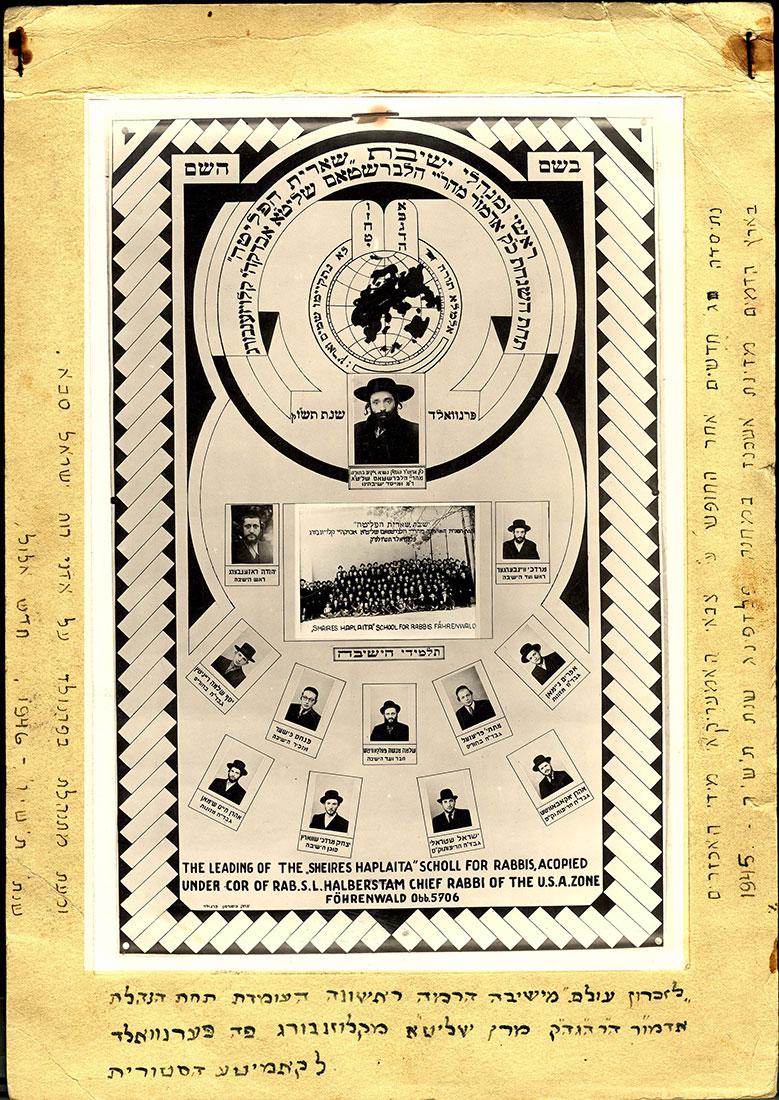

A year later, in the Fährenwald DP Camp, the Klausenberger Rebbe rejected the idea that the traditional words of the Yom Kippur confessional prayer were relevant to the survivors in the DP camps,

“Ashamnu – Did we sin? Bagadnu – Were we unfaithful?… Were we, God forbid, unfaithful to God and did we fail to remain loyal to him? Gazalnu – Did we steal? From whom did we steal in Auschwitz and Mühldorf? … Maradnu – We rebelled? Against whom? We rebelled against you, Master of the Universe?… This Vidui (confession) was not written for us; we are guilty of sins that are not written in the machzor… How many times did many of us pray, 'Master of the Universe, I have no more strength, take my soul so I will not have to recite Modeh Ani (the prayer recited upon waking) anymore'?… We must ask the Almighty to restore our faith and trust in Him. ‘Trust in God forever’… Pour your hearts out to Him.”

A particularly challenging concept to deal with in the context of the Holocaust is that of being God's chosen people. This was addressed head on by Regina Jonas, the first female Orthodox Rabbi. She continued her teaching activities even when incarcerated in Theresienstadt and the final lines in the collection of lectures that she delivered there reflect her selfless attitude and commitment to those around her:

“Our Jewish people was planted by God into history as a blessed nation. ‘Blessed by God’ means to bestow blessings, lovingkindness and loyalty – regardless of place and situation. Humility before God, selfless love for His creatures, sustain the world. It is Israel’s task to build these pillars of the world— man and woman, woman and man alike have taken this upon themselves in Jewish loyalty. Our work in Theresienstadt, arduous and full of trials as it is, also serves this end: to be God’s servants and as such to move from earthly spheres to eternal ones. May all our work be a blessing for Israel’s future (and the future of humanity).