In the summer of 1940, Berlin police officers arrested 70-year-old Siegmund Dornbusch, because he had watched a film despite the fact that it was forbidden for Jews. His case clearly challenges the assumption that it was mostly young Jews who rebelled against Nazi orders.

Dornbusch’s story originates from a larger research project on individual Jewish resistance in Nazi Germany by Prof. Wolf Gruner (University of Southern California), which is due to be published with Yale University Press in 2023. For the purposes of this research, Prof. Gruner developed a broader definition of Jewish resistance. "In the literature on the Holocaust, especially regarding Nazi Germany, there is barely any discussion of elderly Jewish men and women," explains Prof. Gruner, whose findings are featured in the new volume of Yad Vashem Studies (50:2) – the second in a special jubilee series focused on the elderly during the Holocaust. "Most authors mention them only in passing and, if so, as passive elements, waiting for emigration or deportation. They are considered even less in the case of resistance, since the emphasis was traditionally placed on organized resistance and consequently, on the young. When survivors recall in their postwar memoirs and video testimonies how as teenagers they sneaked into theaters prohibited for Jews, it reaffirms this impression." By adding individual acts to group acts against the actions, plans and intentions of the Nazis and their collaborators, continues Prof. Gruner, the given perspective on Jewish resistance dramatically changes. "Based on this new definition, the larger research project identified widespread occurrences of individual Jewish resistance in Greater Germany. One of the main arguments of my study was that for such individual resistance no real differences existed regarding age, socialization, class or education. However, after an invitation to contribute to the anniversary issue of the Yad Vashem Studies, I started to rethink this assumption."

Prof. Gruner's larger project had already benefitted from research at Yad Vashem's archives, where he explored copies of Nazi local administrative records, such as contemporary Gestapo reports and special court records from German archives. Challenging the assumption that resistance may only be learned from Jewish sources, perpetrator sources revealed a variety of rebellious acts of Jews in Nazi Germany. "In my article for Yad Vashem Studies, I concentrate on three forms that emerged from the archives, which are particularly relevant for the individual resistance of the elderly: written criticism of the persecution; oral protest against the Third Reich; and disobeying anti-Jewish legislation."

In 1933, almost eleven percent of the more than 500,000 Jews in Germany were over sixty-five years old. As a result of increasing national and local anti-Jewish measures, many families emigrated, often leaving elderly parents or grandparents behind, isolated and discriminated against. Hence, the percentage of the elderly amongst the Jews of Germany, which at the time were perceived as age 55 and above, increased dramatically.

How did they respond to the tightening of Nazi rules and ever more radicalized anti-Jewish attacks? "Interestingly, police and court documents reveal that many Jews disobeyed anti-Jewish restrictions and Nazi legislation," explains Prof. Gruner. "Starting in 1939, for example, the Nazi state obliged all Jews to carry marked identification cards and adopt the discriminatory middle names 'Israel' (for men) and 'Sara' (for women).

The elderly especially despised being forced to change the names they lived with their whole life.

Unexpectedly, the Nazis could not simply force the discriminatory names onto them. According to German law, they had to apply for a name change. However, many Jewish men and women plainly resisted to file the necessary paperwork. In Berlin, the 68-year-old painter Max Antlers even refused to comply to the order after being summoned to his neighborhood police station in February 1939. Surprisingly, despite tight Nazi surveillance, some Jews managed to hold out for a long time, as did 73-year-old Ida Schneider in Leipzig. When the Gestapo finally discovered her disobedience in 1941, she received seven months in prison for her 'crimes.'”

Some German Jews resisted the additional requirement to inform civil registries about the name changes. Discovered in January 1942, a local court punished Margarete Engel (b. 1879) with two weeks’ jail time. After serving the sentence, she was sent first to Ravensbrück concentration camp, and then murdered in a euthanasia killing facility in Bernburg. Hence, for resisting the Nazi orders to officially record the name adoption of “Sara,” Maragarete ultimately paid with her life.

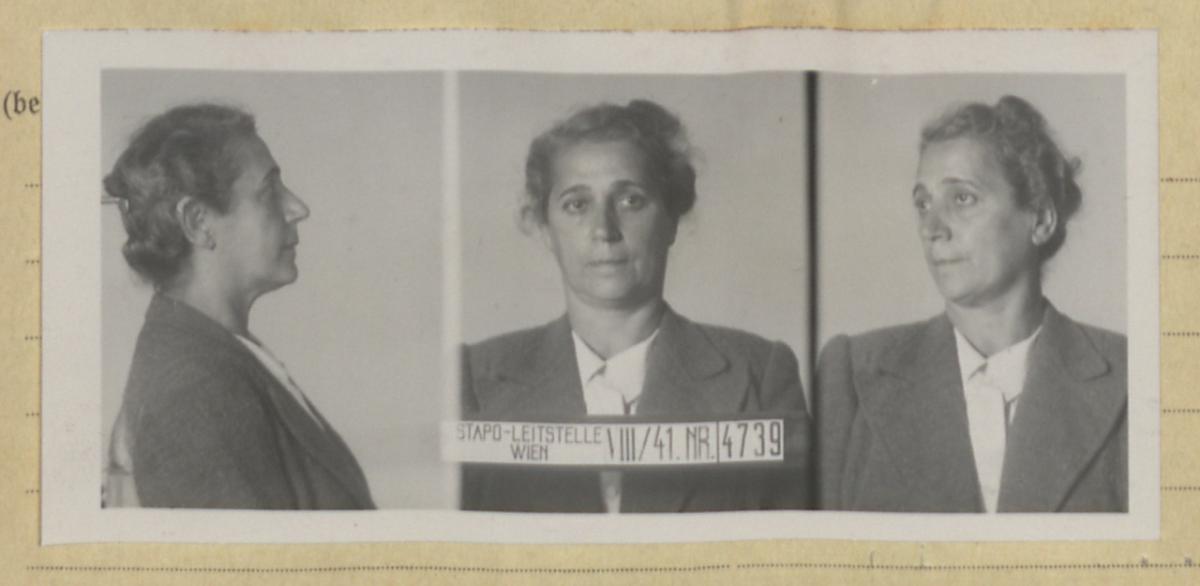

While these elderly Jewish men and women quietly refused to follow Nazi orders, often with drastic consequences, others openly criticized Hitler, the Nazi government, and the anti-Jewish legislation. On 21 August 1939, the lawyer Dr. Arthur Singer (b. 1877) loudly protested at the Vienna city hall that Jews were crammed into so-called “Jews’ houses” and called Hitler a scoundrel. He even urged a dozen of other waiting Jews to storm the offices and beat up the city officials. The Vienna Special Court sentenced Singer to one year in prison. In September 1940, the widow Julie Wagner (b. 1879) publicly called Hitler a bloodhound, and expressed regrets about the previous year's failed assassination attempt in Munich.

For frequently slandering Hitler, the Special Court in Munich punished her with five years in prison.

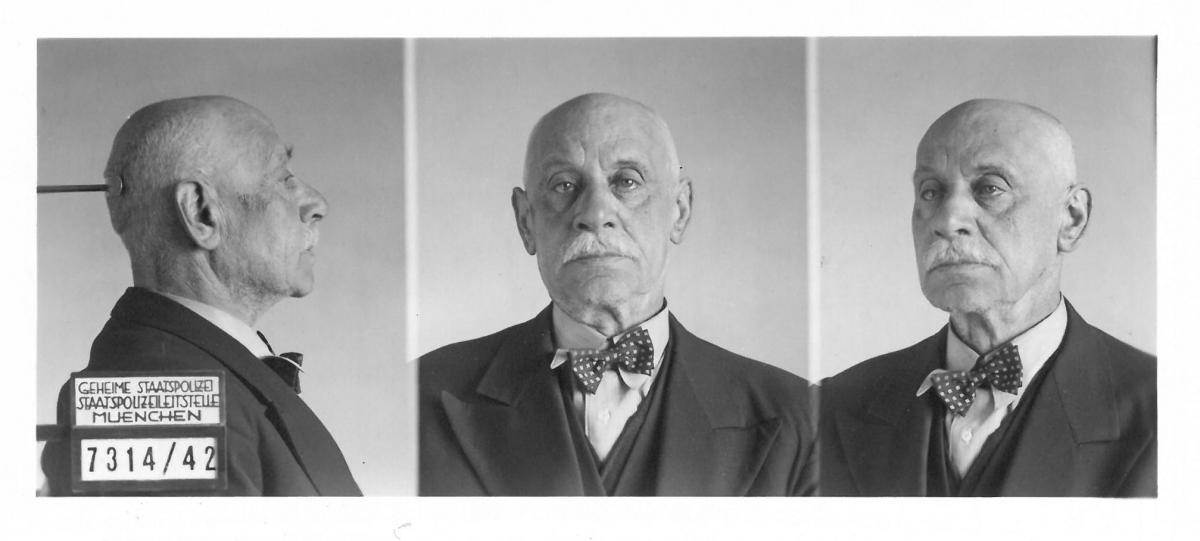

When the Nazi state forced Jews to wear the notorious “yellow star” in the fall of 1941, it was the final straw for Benno Neuburger (b. 1871). In Munich, he applied Hitler stamps to dozens of postcards and wrote abusive comments such as “The eternal mass murderer Hitler. Disgusting!” on them, before mailing them out anonymously. In the spring of 1942, after the Gestapo arrested Neuburger, they beat him in order to obtain his confession. The Nazi People’s Court in Berlin found Neuburger guilty of “treason.” For his written resistance, he paid the ultimate price. He was decapitated in September 1942.

"Introducing a broader concept of resistance changes our understanding of Jewish attitudes in Nazi Germany," Prof. Gruner concludes.

"Surprisingly, the Jewish elderly – as shown in my article with striking examples – disobeyed anti-Jewish measures, protested in public against the persecution, and objected to the anti-Jewish policies in written form. In most cases, the Nazis punished the Jewish elderly with harsh sentences, and some even were murdered – which reveals that the German authorities perceived the individual resistance acts of elderly Jews as a very real threat."