Yad Vashem Archives

This month a special event took place at Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center, with survivor Lion "Bob" Rubin who escaped with his family from Germany to England just days before World War II broke out.

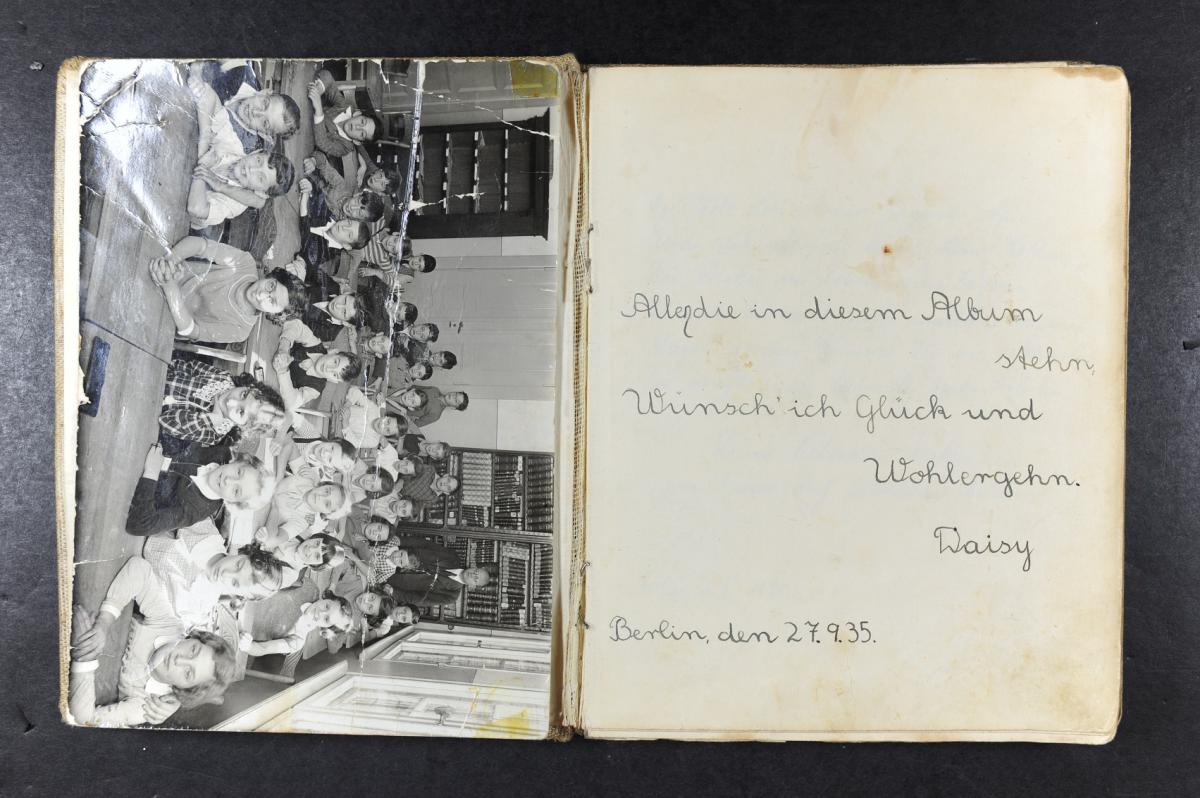

Yad Vashem received a suitcase - used by Bob's sister Daisy during her journey on the Kindertransport in 1939 - along with the suitcase were dozens of original documents and photographs detailing the life and escape of the family from Nazi- Germany, including letters, birth certificates, memoirs and official documents.

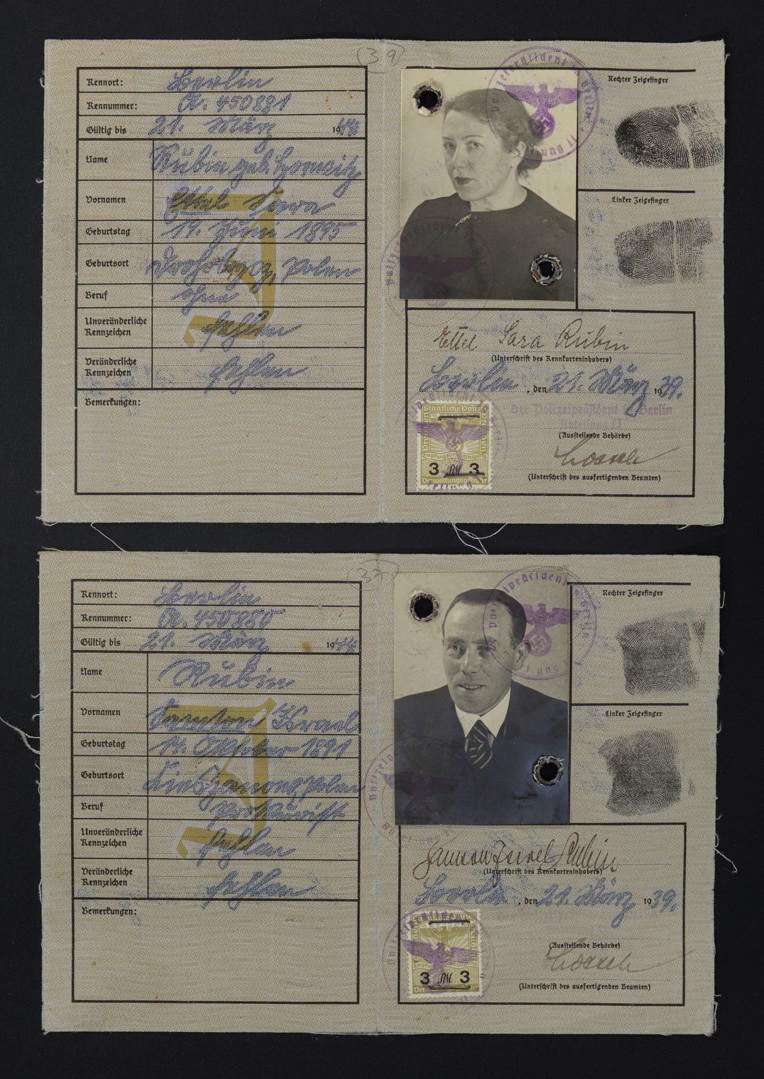

Most of the documents presented to Yad Vashem belonged to Daisy's parents – Samson and Ettel Rubin. Born in Poland, the couple lived in Austria for many years before moving to Berlin in 1932. Following the November 1938 Kristallnacht pogrom and in light of the increasingly antisemitic climate, they began looking for ways to leave Germany.

Ultimately, they obtained permission to send Daisy on a Kindertransport in June 1939. Then, through the assistance of British Righteous Among the Nations Francis Foley, the family received visas and escaped to England in August 1939, just 25 days before the outbreak of World War II. With the exception of one of Ettel's brothers who moved to the Land of Israel before the war – their entire extended family was murdered in the Holocaust.

Daisy, who passed away in 2011, first stayed in Rabbi Solomon Schonfeld's hostel for Jewish refugee girls in Sunderland and later reunited with her family in London. A total of 27 girls stayed at the hostel throughout the war and many of their descendants -who now live in Israel - were present at the event in Jerusalem.

"If it wasn't for these visas we all certainly would have died in the Holocaust," said Bob Rubin

"If it wasn't for these visas we all certainly would have died in the Holocaust," said Bob Rubin, a former black cab driver who has lived in London since narrowly escaping the Holocaust at the age of two. "I can't know how hard it must have been for my parents to send their daughter away on the Kindertransport – not knowing if they will ever see her again. But we were the lucky ones. None of the other girls from Sunderland ever saw their parents again."

These documents present a fascinating insight into the Holocaust and the personal experiences of a family who made their way from Eastern Europe, to Austria, then Germany and finally to safety in England. Included in the suitcase were official travel documents issued by the Nazi-regime to the family in 1939 as well as Rubin family photo albums from Poland, Austria and England.

The family also donated a diary Daisy kept while in Germany. Among its pages are messages from her school friends, many of whom didn’t survive the Holocaust. "All her friends and teachers wrote in her diary. This is the only proof that some of these girls ever existed. They were killed during the war and left no record behind. What they wrote in my mother's diary is the only remaining testament to their lives," said Susan Herold. Daisy's daughter – who gifted the suitcase filled with her mother's artifacts.

"The staff at Yad Vashem did an amazing job of organising such a beautiful event and I want to thank everyone who made it possible. I am passing on the last of my mother's possessions from that era with mixed emotions. It’s hard to part with these objects, but I know it is for an important purpose."

The collection includes the family's German passports and identity cards dated from 1939. The documents are clearly stamped (on the front) with the Nazi insignia and are marked with a 'J' to identify them as Jews. The middle name 'Israel' has been added to Samson's name and both his wife and daughter have the middle name 'Sarah' – part of the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 designed to separate and identify Jews. After the war, the family received British citizenship and their new passports were also presented in the suitcase.

Dr. Haim Gertner, Director of Yad Vashem's Archives Division and Fred Hillman Chair for Holocaust Documentation, spoke at the event about the importance of the "Gathering the Fragments" campaign, which aims to collect Holocaust-era artifacts, documents and artworks still kept in private homes, and under threat of disintegration. The process of collecting the items has also resulted in the documentation of the narratives that lie behind each one, a mosaic of accounts that make up the story of the Shoah. To date the program has seen over 250,000 items entrusted into Yad Vashem's hands. All the information is also archived and uploaded online so the public can access the stories and share them with others.

"Yad Vashem is in a race against time," said Dr. Gertner. 'We collect over a thousand survivor testimonies annually to help people learn about the Holocaust – not just as a historical event but as something people lived through. The Nazis not only murdered the Jews, but they also wanted to wipe out their memories. We work to restore these memories, to honour the victims and to teach the coming generations about what happened"

The Hostel in Sunderland

Around 50 people attended the event at Yad Vashem's Complex on the Mount of Remembrance in Jerusalem. Most of whom were descendants of girls who had been on the Kindertransport and stayed at the hostel in Sunderland.

One item in the collection is a letter received by Samson Rubin, dated 7 February 1939, from the North London Committee for Refugee Children from Germany and Austria. It describes Daisy's acceptance to the Kindertransport and the English weather she would face on the arrival to Sunderland.

"I am very glad to tell you that just today we have been offered a home for your daughter Daisy. The new hostle [sic] opened in Sunderland, has kindly consented to take your daughter. You can get your daughter's things ready, for a departure in about 4 to 5 weeks time. It would also be advisable to buy her some woolen-undercloth and slippers, and not too heavy boots, as Sunderland is rather up North, and therefore rather cold."

Freida Schalkowski, another Kindertransport refugee who stayed at the hostel and later moved to Israel, was also present at the event as many families of the girls who found refuge in Sunderland were reunited. She retold her story to those present, recounting how her family moved from Poland to Munich in the 1920s.

"Things were very bad financially in Poland so we moved to Germany because it was safer and richer," she recalled. "After the Nazis took over, things became very bad for us. My older sister and I were sent to live on the other side of the city because our family was scared.

"One Shabbat my sister decided we would walk to synagogue – over an hour away. Saturday was the day that the Nazis held their rallies in the square in town and we had to walk through hundreds of thousands of people. But we could pass for Germans and my sister insisted we go. We got to the synagogue and I remember our family being so happy to see us. They lifted us up on their shoulders during the service and sang and danced."

In 1938, Freida was sent on the Kindertransport and ended up in Sunderland. After the war, she and many of the other girls moved to Israel, where they were founding members of two religious kibbutzim – Lavi and Hofetz Haim.

"I remember arriving to England for the first time on the train. We were each given an English cup of tea but we had absolutely no idea what it was. We didn't know what to do so we threw it out the window. Some of the girls – including myself – kept kosher, so we couldn't eat most of the food. We got by eating fruits and other such things until arriving at the hostel.

"I have to give a special thanks to the people in Sunderland. They were so good to us. I remember the first time we went to the beach and people bought ice-cream for us. The whole hostel had been donated by the Jewish community and everything was brand new. The schools didn't open in 1939 because of the war, but they made sure we learned English and a rabbi came in to teach us Jewish studies.

"I remember many of the girls would cry every night before going to sleep. They missed their families, and it was very hard for them to be away from home. At first, we had correspondence with our families through the Red Cross – but that slowed down and then stopped completely after the war started.

"We had no idea during the war of what was happening to the Jews in Europe – to our families. But after the war we learned about all the horrors. Before every movie in Britain, they would show the news and we quickly learned about what happened. We saw videos of British soldiers liberating Bergen-Belsen. We all tried to find out about the fates of members of our families in Europe through the Red Cross. Unfortunately, none survived."

Bob Rubin spoke about his sister at the event. Daisy wrote extensively, meticulously keeping her diaries alongside her personal documents and photographs in order to tell her family's story. She later authored a book – along with three childhood friends – about life in Berlin and the Holocaust, called And Then There Were Four, which was published in 2006.

"Daisy wrote a lot about the trip," explained her younger brother. "She described the great trauma it caused her and how hard it was for her to say goodbye to her family at the train station. She tried to put on a brave face and be positive. She described it as an 'adventure'. Aged 12, she was one of the oldest girls on the trip and was put in charge of a younger girl. She wrote about the goodness of the people at the first station they arrived at in Holland, who had prepared food and drinks for them.

"They arrived at Liverpool Street Station in London on 6 June and every girl went to a different place. She wrote wonderfully about her time in Sunderland. Everyone there treated them so well. Everything in the hostel in Sunderland was brand new and the Jewish community paid for it all. In 1942, we went to King's Cross Station and this young women approached us. My parents told me it was my sister – she was still only sixteen. It's the first memory I have of meeting her.

"On leaving school in London, Daisy worked as an apprentice in a dressmaking firm. She also went to evening classes to learn about fashion design and dressmaking. For her, this was the defining moment in her life, and it is something she retained and passed on to her daughters and granddaughters.

"After a short time in this industry, she decided she wanted to learn about haut couture (elegant dressmaking) and she went to a firm in Mayfair whose clientele included Vivien Leigh, Deborah Kerr and the Duchess of Kent. One of her most exciting memories from that time was when Princess Alexandra of Greece got married and Daisy – as she had the same 18-inch waist as the Duchess of Kent – helped to alter her dress."

The family's escape from Nazi Germany

The documents gifted to Yad Vashem present a fascinating account of the prewar circumstances of the Rubin Family. Samson (b.1891) and Ettel (b.1895) were both born in Galicia, part of modern-day Poland but then a region of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Samson served in the Austrian Army during World War I – he was deployed to a hospital. The couple later moved to Vienna.

Bob explained: "Our parents were very wealthy thanks to my father's job. A friend of his from the Austrian army - who was also from Poland - approached him and asked him to manage the Berlin branch of his business. The company was called Erko and sold radium heating pads which people used when they slept. It was a very innovative idea and they were sold all over Europe.

"They moved to Berlin in 1932, and Daisy started to learn in a German school. In her memoirs, she recalls how the teacher was an ardent Nazi and used to punish all the Jewish girls by making them stand with their face to the wall. In 1935, they banned Jews from studying in German schools, and Daisy moved to a Jewish school. She was very lucky, because they were taught by Jewish PHD professors who had been banned from teaching in universities.

"Unfortunately my grandfather was sent to Buchenwald during Kristallnacht where he later died. We had to pay 10 Marks to get an urn full of his ashes back."

The suitcase donated to Yad Vashem also contains a letter written by Daisy in 1999 after learning the identity of the man who saved her family by issuing them visas to England.

Samson had been a successful businessman, managing his company's Berlin branch until the Germans banned Jews from management positions in 1938. A chance meeting in Berlin with Lord Lister – a former business acquaintance – allowed Samson to receive a work visa to England and escape from Nazi Germany only 25 days before the war broke out.

Despite the fact that his wife and son had not been issued with visas, the British Embassy in Berlin nonetheless stamped their passports. In 1999, it was revealed that the man responsible for saving the Rubin family was Captain Francis Foley, a British spy serving as the Passport Control Officer in the embassy in Berlin. He used his position to issue more than 10,000 visas to Jews looking to escape the Nazi regime.

Somerset-born Foley, who died in 1958, did this at great personal risk to himself as both the Nazi regime and the British Foreign Office were opposed to his actions. He did not enjoy diplomatic immunity in Berlin and could have been killed by the Germans if they had discovered he was issuing illegal visas to Jews. He was recognized as a Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem in 1999.

Daisy wrote in her letter: "My family tried to emigrate to anywhere after the "Austrian Anschluss [Nazi-occupation]" in March 1938. We were Austrian citizens, but could only get an American affidavit to enter the USA four years later [1942].

"The firm that had bought the patent in Britain [from her father's company] was headed by Lord Lister. He came to the Berlin office in May 1939 and my father approached him if he could possibly get a visa to go to England. In the middle of June 1939, a six-month visitor's visa was received by my father, only for him and not for my mother and two-year-old brother.

"He lined up for hours at the British Consulate and when his turn came and he presented his passport and visa certificate, the clerk asked him if he had family. 'Yes'; my father replied, 'a wife and son. My daughter left for England last week on the Kindertransport.' 'Do you have your wife's passport on you?' The clerk asked.

"Dad handed over my mother's passport. Both passports were taken away and after some time returned to my father. It was only after he got back home that he realized that both passports had been issued with visas.

"They all arrived in England on 9 August 1939. The war broke out on 3 September. I have never forgotten this story, and am happy to know the name of the person who saved the lives of my mother and brother 60 years ago."