Chalk and charcoal on paper

Yad Vashem Art Collection

Acrylic on canvas 80x105 cm

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem

Gift of the artist

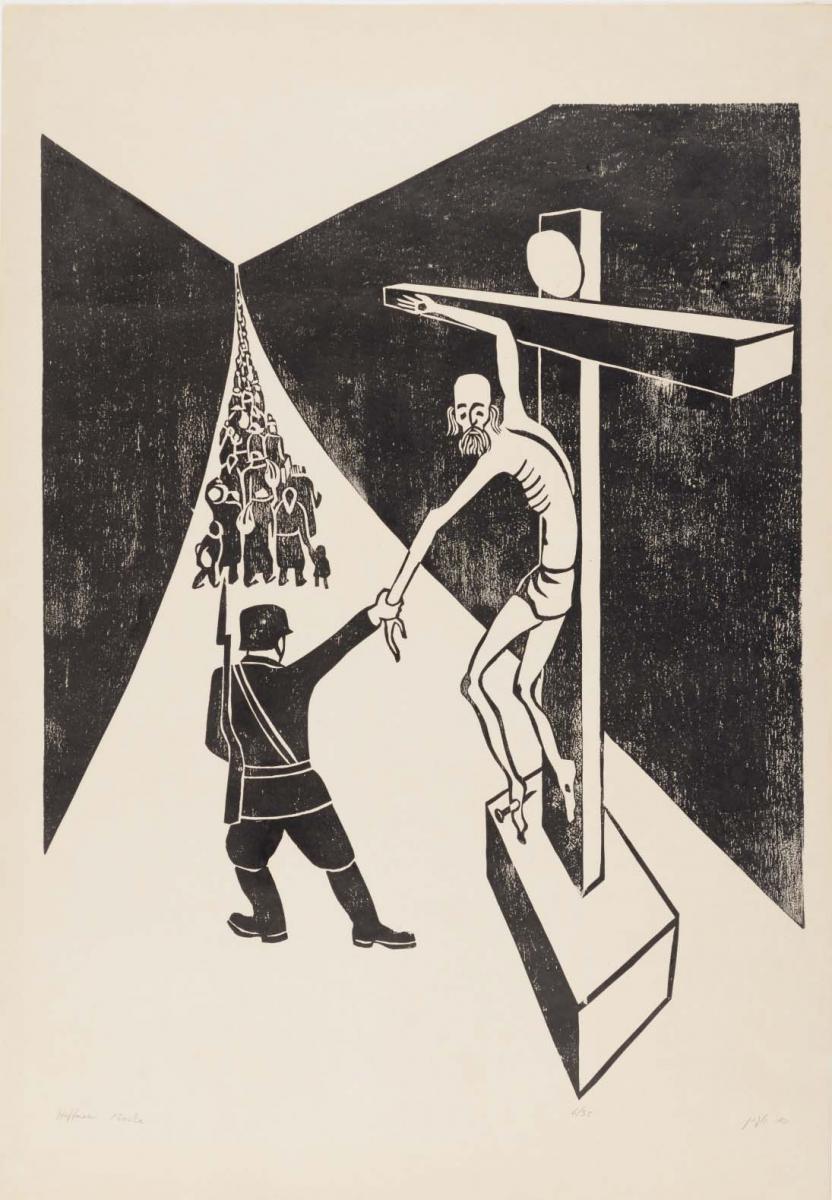

Woodcut on paper

97.5X67.4

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem

In the final blog of this series, we explore unique artistic endeavors that connected those who created them with their ancestors, while expressing the anguish and anticipation for an end to the maelstrom in which they were caught.

In their art, Holocaust survivors searched Jewish tradition for visual language to express what they had experienced. They leaned on the midrashic form of biblical interpretation, reimagining traditional Jewish texts to reflect the conditions under which they were living and the traumatic experiences they had undergone.

Ludwig Meidner's work "In Memory of our Destroyed Synagogues in Germany 10/11/1938" creates a parallel between the destruction of the First Temple and the burning of synagogues that he witnessed in Cologne. He made an iconographic reference to Rembrandt‘s painting of Belshazzar’s feast, an event in the Book of Daniel at which a mysterious hand appears and inscribes an indecipherable phrase upon the wall, an event that was interpreted as a prediction of the imminent fall of the Babylonian king. Drawn following his escape to England in 1939, the work expresses his hope for the downfall of the Third Reich.

In “The Letters Are Soaring,” Joseph Wisina paints a pile of books, phylacteries and Torah scrolls being placed on a fire as letters rise up in the flames. The image of book burnings organized by the Nazis is combined with a reference to the Talmudic story of Rabbi Hanina who was burnt on a pyre by the Romans whilst wrapped in a Torah scroll. As he was dying, his students asked what he could see, to which he replied, "The parchment is burning, but the letters are taking flight!" The events of the narrative have been variously understood to predict the downfall of Rome or to show that the holy letters survived, uncharred by those who wished to destroy Jewish tradition.

For both of these survivor-artists, the destruction of the two Holy Temples served as the archetypal national trauma to which they referred in their art and, in both cases, that reference contained an element of hope. Others however could not find images that they felt were adequate. They looked outside of Jewish tradition, adopting depictions of the Crucifixion as the only visual language strong enough to depict their pain. Marc Chagall used a crucified Jew as a symbol of the Jewish people’s ordeal in Europe during the Holocaust period and that imagery was later adopted by other survivors such as Joseph Bau and Moshe Hoffman.

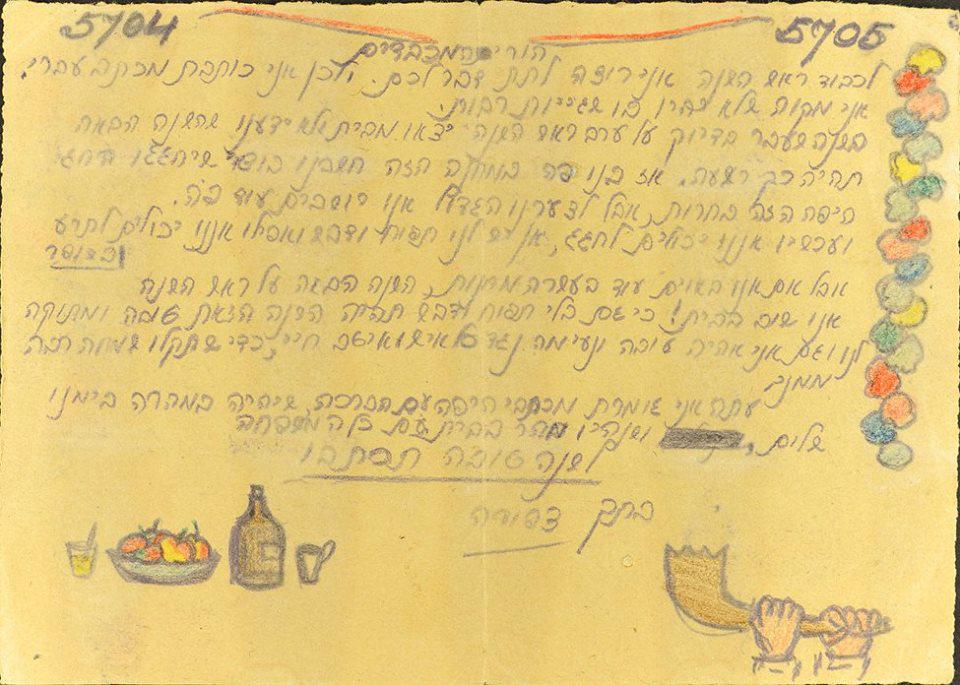

Even children internalized the difficulties posed by a time of year associated with looking to the future. In her Rosh Hashana greetings to her parents, 13-year-old Fanny Dasberg explicitly drew comparisons between celebrating Rosh Hashanah – the Jewish new year – under normal conditions and observing it in Bergen Belsen: "We will have a happy and sweet New Year even without apple and honey."

Fanny relates to how Rosh Hashanah is a time of looking forward to the coming year, to the challenges that they had faced since the previous Rosh Hashanah, and her hopes for the year that was just beginning whilst acknowledging the difficulties in which they found themselves.

Her wishes for the coming year adapt phraseology from the language of prayer, “May peace come quickly in our days, and may we speedily return home with all the family,” concluding with the traditional but especially poignant new year's greeting, "May you be inscribed for a good year."

In all four parts of this series – Then as Now, Prayers, Sermons and Art – we see how familiarity with midrashic methods of interpretation inspired many Jewish men, women and children in Nazi-occupied countries to engage with or respond to Jewish texts and traditions in ways that maintained their relevance in a new and painful context. Texts and traditions could be understood or adapted to provide a commentary on the circumstances in which the Jews found themselves, often providing a measure of hope in an otherwise desperate situation, but also giving new depths and understandings to established teachings or as a way to reexamine the nature of their eternal relationship with God.