Recently, Yad Vashem was honored to host Wlodek Tabaczynski and his daughter Zosia, who had come to see the incredible restoration work carried out on the wartime diary of Wlodek's father, Stefan (né Alfred Zielony).

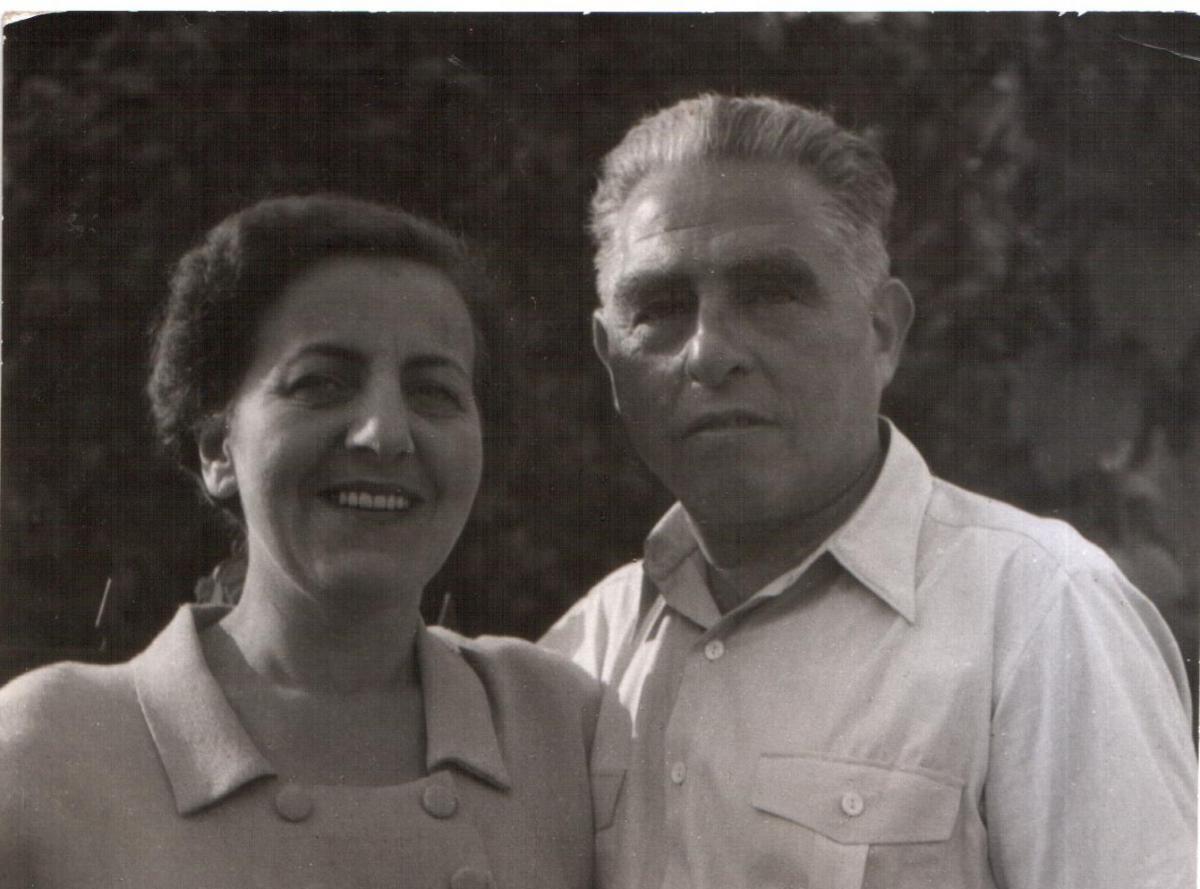

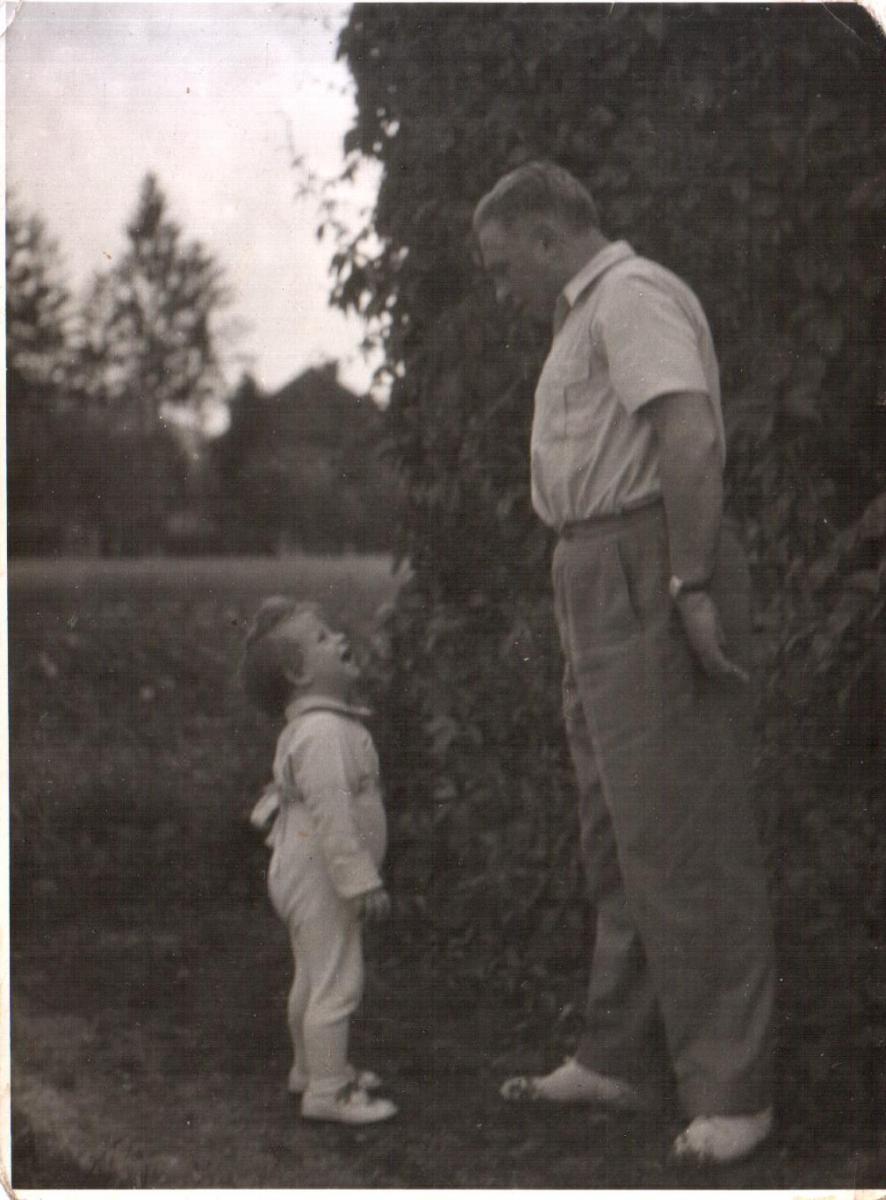

Alfred Zielony was born in 1897 in Warsaw, the youngest child in a Jewish family. His father and one of his brothers died before WWII, and another brother, Bernard, immigrated to Israel in 1921. The rest of the family remained in Warsaw, and were duly incarcerated by the Nazis in the ghetto. It was there that one of Alfred's sisters, Balbina, died of typhus. In August 1942, his wife and child were deported to Treblinka along with his mother, where they were murdered. Two other siblings were also murdered, and Alfred was left alone, hiding in the ghetto. After the ghetto was liquidated, a friend of his, Irena, who had worked in the family business before the war, managed to smuggle him to safety. At the war's end, Alfred changed his name to Stefan Tabaczynski and married Irena. Stefan/Alfred passed away in 1956, when Wlodek was just two years old.

In the 1950s, Alexander (Alex) Zielony, the son of Bernard (who had come to Israel before the war), visited Washington for government business. On his way back to Israel, Alex decided to take a detour via Warsaw and visit his aunt, Irena, and his two cousins, Wlodek and Andrzej. During the trip, Irena showed Alex the crumbling remains of a diary her late husband had written during his time in hiding. The diary had been severely damaged by fire and water during the Polish uprising.

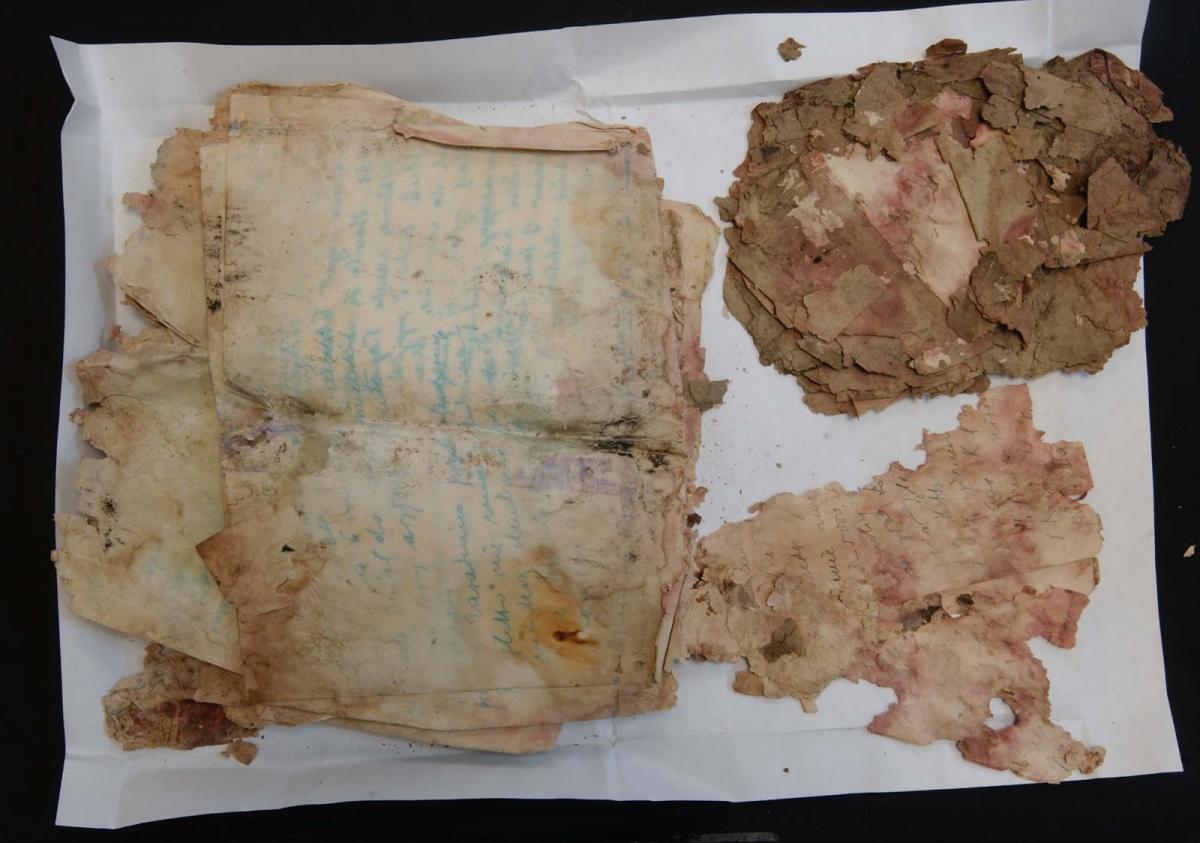

In 2006, Wlodek came on his first trip to Israel and, at his cousin Alex's request, brought the diary with him. Alex immediately suggested giving the diary to Yad Vashem, in the hope that restoration experts could help the family save the deteriorating pages and even decipher some of Alfred's testimony.

"The diary was in terrible shape," recounts Yad Vashem's Archives Director Dr. Haim Gertner. "It was little more than a mass of singed and crumbling papers. We treated it with immense care and expertise at our Paper Restoration Laboratory, first carefully separating the pages and then restoring and preserving each page as far as was possible. After years of painstaking labor, the diary now comprises twelve complete and four partial pages – although because of the difficult state in which they arrived, they are barely legible. While certain words and even parts of sentences – all written in Polish or German – can be made out, it was near impossible to understand the general context.

Even employing the most advanced methods of handwriting reconstruction, police identification lab equipment and the help of antiques and other experts in Israel and abroad, we were still unable to decipher the diary, or even say with certainty when during the war or where it was written. Nevertheless, we were extremely satisfied that at least the diary itself had been saved."

Last week, Wlodek Tabaczynski and his daughter Zosia came to Israel to celebrate the 100th birthday of Wlodek's cousin Alex. Dr. Gertner showed Wlodek Yad Vashem's online Central Database of Shoah Victims' Names, within seconds calling up all 18 Pages of Testimony Alex Zielony had filled out in 2008 for individual members of his family who were murdered during the Shoah. Seeing all of this information recorded for posterity was very important for Wlodek – a project manager – and Zosia, who is a teacher.

However, Wlodek was visibly moved when he was shown the diary and was able to see its pages for the first time. He recalled how his father had studied law and then practiced journalism – eventually heading the Polish Society of Journalists (PAP) after the war. "He loved to write," he explained, and asked to touch the actual pages of the diary. "I can't help it," he said. "It's just like touching my father again."

In his home, Wlodek has a separate page that Alfred wrote, on which he recorded the names of all his family members that died – when, how and where – in succinct notes. At the end of the list, Alfred wrote: "…but I could write tomes about how I survived."

As Wlodek was familiar with his father's challenging handwriting, he was able to make out a few lines from the diary. For example, there is a description of how those Jews living in the ghetto who had work certificates would gather early each morning at the checkpoint at the ghetto gates, and return in the evening, bringing with them whatever food they had managed to bargain or buy to smuggle back into the ghetto. "But the officers usually took this food away," recalled Alfred – leaving the despondent men to return empty-handed to their starving families. "For the first time, we realized that this diary was most likely written in the Warsaw ghetto itself, and describes daily life there," said Dr. Gertner.

Wlodek ended his visit by pledging to devote his time to deciphering as much of the diary as he can – bringing Yad Vashem closer than ever to untangling the content of this rare piece of documentary testimony about life in the Warsaw ghetto.