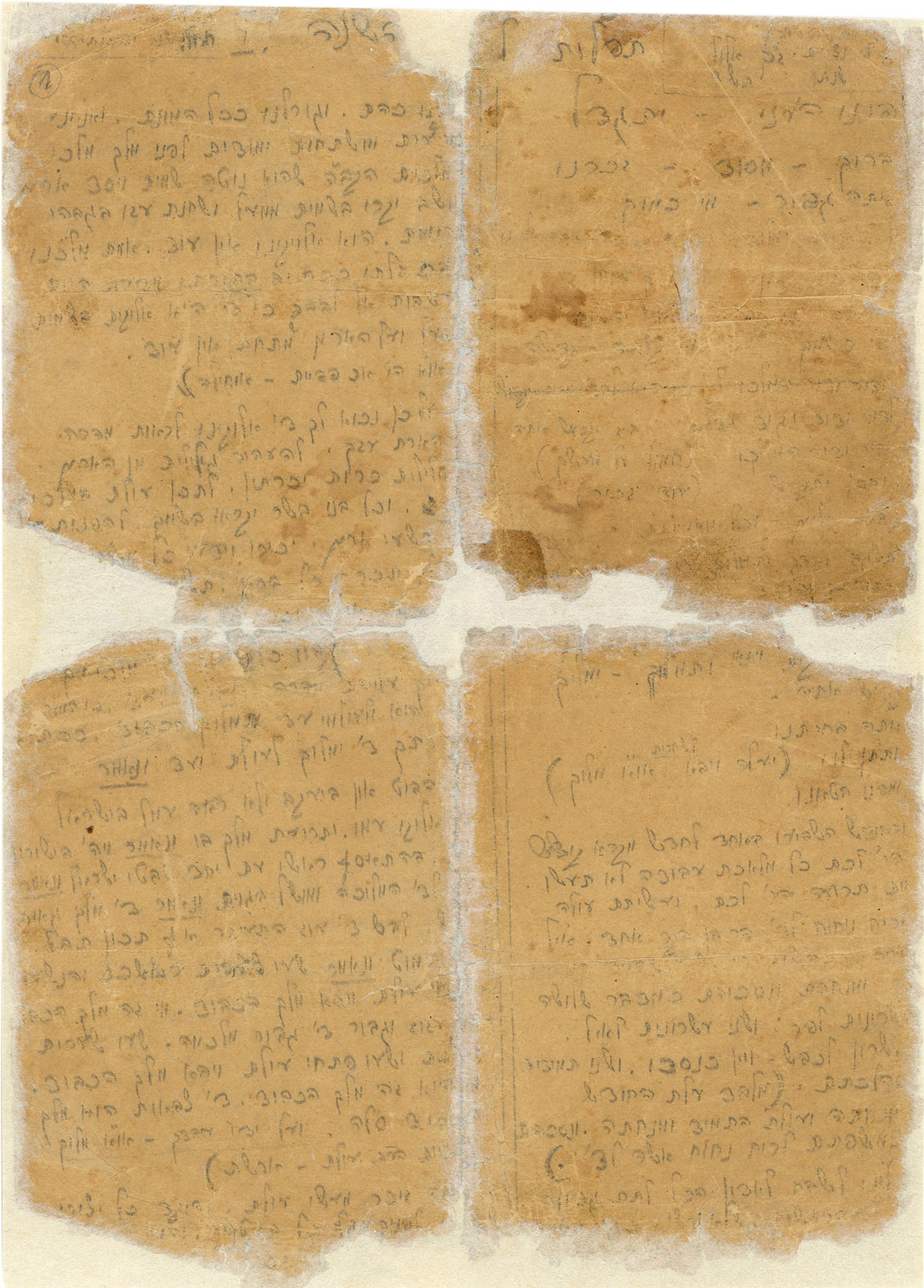

Prayers for the new year written in pencil on cement bags by Naftali Stern on the eve of the Jewish year 5705 – 1944 in the Wolfsberg forced labor camp in Germany

Just three months before he died, Naftali Stern visited Yad Vashem on Holocaust Remembrance Day, 1978. Naftali, an elderly man in his late 70’s, took out an envelope containing frayed pages; written on them were the prayers for the Jewish New Year (Rosh Hashanah Musaf), the longest in Jewish liturgy. Naftali proceeded to share his story.

Prior to the Holocaust, he had lived in Satu Mare, North Transylvania, Romania, together with his wife and four young children. On a fateful day in May 1944, Naftali, his wife Bluma and his children were deported to Auschwitz. Upon their arrival, Naftali was separated from his family. Bluma and the children were murdered in the gas chambers and Naftali, considered strong at 34 years old, was sent to Wolfsberg, a forced labor camp in Germany. In Wolfsberg, the inmates, including Naftali, were forced to dig tunnels and trenches to serve as a defensible bunker for the retreating German army and high command.

As the Jewish New Year approached, Naftali began to reflect upon the Rosh Hashanah services. He sold his daily ration of bread in order to obtain a pencil and some sacks that had held cement. He tore the paper sacks into small squares and began to write, from memory, the entire Rosh Hashanah service in a scrawl.

The Nazi officer in the camp allowed the inmates to gather together and hold prayers for the Rosh Hashanah in lieu of breakfast. Naftali, who by virtue of his sweet voice had been a cantor in Satu Mare, led the services, an event the survivors remember as a special moment in the life of the camp.

Naftali hid the pages on his body until his liberation in 1945. During the next 30 years, each Rosh Hashanah, Naftali held the crumbling pages under his right hand as he prayed. After the war he rebuilt his life, established a new family and immigrated to Israel. When Naftali presented the disintegrating papers to Yad Vashem, he noted that he was donating them for safekeeping. Naftali stressed that it was vital that future generations understand that in spite of the survivors’ harrowing experiences during the Holocaust they maintained their spirit, embraced their Jewish identity and never lost hope. In a trembling voice Naftali said “I pray that each subsequent generation will stay true to their Jewish identity and be a link in a long chain."

Naftali's machzor is on display in the Holocaust History Museum at Yad Vashem along with thousands of similar pieces, each telling its own unique story with its own special meaning. Each of these artifacts sheds light on the rich tapestry of European Jewish life prior to WWII and the rise of the Nazi regime; the vanished world of millions of Jews and the survivors incredible return to life.

The Wolfsberg Machzor, available from Yad Vashem Publications, includes a copy of Naftali's handwritten prayers as well as articles about maintaining faith during the Holocaust.