- Alexander Litin and Ida Shenderovich, eds., History of Mogilev Jewry, (Mogilev, 2009), book 2, 142-143 (Russian)

- The English translation is cited from: The Untold Stories: The Murder Sites of the Jews in the Occupied Territories of the Former USSR, "Mogilev," Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 2010. The testimony is translated from the Russian from: Alexander Litin and Ida Shenderovich, eds., History of Mogilev Jewry, book 2, pp. 163-164.

- Yitzhak Arad, The History of the Holocaust: the Soviet Union and the Annexed Territories, (Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 2004), part 1, 346 (Hebrew). Most of the subsequent references to Arad’s book are to the Hebrew edition, unless indicated otherwise.

- The passages are cited from the war diary, see "An ort und Stelle Erschossen", Der Spiegel, p. 44 (1986). Cited here from Yitzhak Arad, The Holocaust in the Soviet Union, (University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and Yad vashem, Jerusalem, 2009), 188.

- See The Untold Stories: The Murder Sites of the Jews in the Occupied Territories of the Former USSR, "Mogilev," Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 2010.

- See The Untold Stories: The Murder Sites of the Jews in the Occupied Territories of the Former USSR, "Mogilev," Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 2010.

- Browning, Christopher, The Origins of the Final Solution, (Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 2004), 298-9.

- The English translation is cited from: The Untold Stories: The Murder Sites of the Jews in the Occupied Territories of the Former USSR, "Mogilev," Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 2010. The testimony is translated from: Alexander Litin and Ida Shenderovich, eds. History of Mogilev Jewry, book 2, 159-160.

- Christian Gerlach, "Failure of Plans for an SS Extermination Camp in Mogilev, Belorussia", Holocaust and Genocide Studies, VI1 Nl, Spring 1997, pp. 60-78.

- Yitzhak Arad, The Einsatzgruppen reports: Selections from the Dispatches of the Nazi Death Squads' Campaign Against the Jews July 1941-January 1943, Holocaust Library, 1989, doc. 133, pp. 234-235. Cited here from Yitzhak Arad, The Holocaust in the Soviet Union, (University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and Yad vashem, Jerusalem, 2009), 188.

- Alexander Litin and Ida Shenderovich, eds., History of Mogilev Jewry, book 2, 163-164. Cited here in English from: The Untold Stories: The Murder Sites of the Jews in the Occupied Territories of the Former USSR, Mogilev, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 2010 “Mogilev”, Odot Hashoah.

- USHMMA, Fond RG, Opis 53006, Delo M, Reel 5, Mogilev Regional Archive (Mogilevski Oblastnyi Arkhiv), Fond 418, Opis 1, Delo 1 . Based on the Hebrew translation in Yitzhak Arad, The History of the Holocaust, (Yad Vashem, Jerusalem 2004), part 2, 738 (Hebrew).

- Yitzhak Arad, The History of the Holocaust, part 2, 747.

- Mixed marriages were a widespread phenomenon in the Soviet Union. On February 1st, 1942, the Mogilev authorities published a definition according to which a Jew is someone who has at least three Jewish grandparents or who holds the Jewish faith. See Alexander Litin and Ida Shenderovich, eds., History of Mogilev Jewry, book 2, 151.

- Gerlach, "Failure of Plans", 60-78.

- Ibid, 69.

- Ibid.

- Arad, The Einsatzgruppen reports, 133, p. 232, cited in Arad, The History of the Holocaust, part 2, 884.

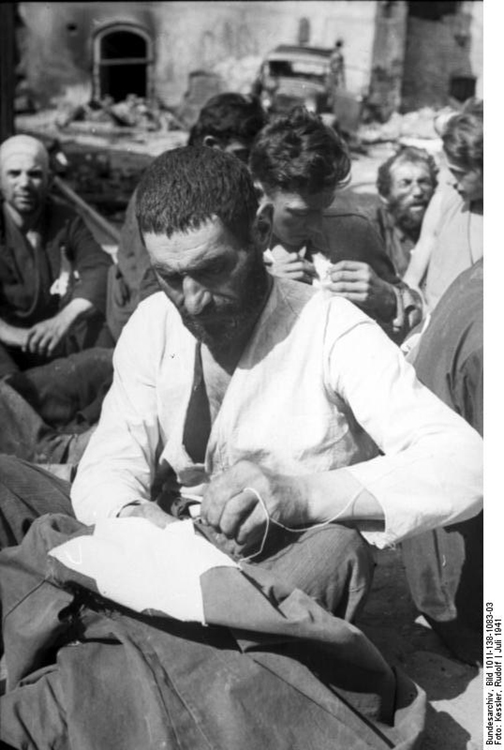

Many of Mogilev’s Jews left the city with the start of Operation Barbarossa on June 22nd, 1941. The city was occupied by the Germans on July 26th after about two weeks of the Red Army and civic militia resistance. It was gradually surrounded and bombarded to ruins. According to the ChGK report, (the Soviet Extraordinary Commission), some 10,000 residents were killed defending the city among whom were an estimated 2000 Jews.1

After the appointment of a Jewish council (similar to a Judenrat) in August 1941, the Germans conducted a census which showed a significant decrease in the number of Jews in the city. The census registered 6,437 Jews, among whom were 2,090 children under 15. We can assume that the actual number of Jews in the city was higher and that some either avoided registration or registered under an assumed identity. At the same time the Jews were required to wear a yellow badge of shame.

On August 13th, the Jews were ordered to move to the ghetto which was set up next to the Jewish cemetery at the order of the German military command signed by the Belarusian mayor. The ghetto area was too small to accommodate the Mogilev Jews, let alone the Jews from the adjacent towns and villages who were also evicted from their homes and placed in the Mogilev ghetto. On September 25th, the city mayor ordered the Jews to move to a new ghetto on the other side of the Dubrovenka river. The Jews were to relocate within five days under the oversight of the Jewish council and a separating fence was to be set up by the Jews themselves.

The relocation of the Jews to the ghetto was witnessed by Mogilev residents. Valentina Belkovskaya, who was born in Mogilev in 1928 and lived in the city during World War II, later testified:

One day, early in the morning (at dawn) we were awakened by loud cries, screaming, the crying of children, and the barking of dogs. We were far from Dubrovenka [the area where the ghetto was located], but the noises were so loud that we could hear them well. It was so terrible that it is impossible to describe it. It was said that all the Jews were driven out of their houses and loaded into covered trucks. They were forbidden to take their belongings. Those unable to walk were shot in their houses, in their beds [...]. Afterwards the [local] policemen searched the houses, collecting the abandoned goods, which were then sold in special shops. People said that the rings, earrings, and other jewelry were taken by Germans. We, the children, went the next day toward evening to see what was left there. It was a horrible sight: there were empty, abandoned houses and hungry dogs. In one of the houses we saw the dead body of an old man in his bed and we ran out with cries of terror.2

The Germans murdered 113 Jews during the transfer to the ghetto on the charge of refusal to relocate. The ghetto was encircled with barbed wire by the middle of October 1941. Inside it was overcrowded and the Jews were starving due to the absence of food supply. The Jewish council recruited 15 policemen to the Jewish police force at the order of the Germans. They were equipped with clubs and charged to maintain order in the ghetto. The Jews were routinely accused of spreading rumours, of disobeying the orders of the Germans, of not wearing the yellow badge and of refusal to relocate to the ghetto. The consequences were dire – 632 Jews were murdered because of these accusations, half of them being women.3

In September 1941 the command of Einsatzkommando 8 of Einsatzgruppe B moved to Mogilev and its soldiers took part in two major anti-Jewish actions. The first of the two actions was carried out on 2-3rd of October 1941 by the police battalion 322 of the Ordnungspolizei (ORPO) under the command of Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski. The action was recorded in the war diary:

On October 2nd […] at 15:30, the 9th companion … together with HQ staff of the Higher SS and Police Leader “Center” and the Ukrainian auxiliary police, carried out an action in the ghetto in Mogilev […] 65 were shot trying to escape [ …] October 3 [...] Companies 7 and 9 [...] executed 2,208 male and female Jews in a forest outside of Mogilev.4

In the course of the action the Jews were transported to the Jewish cemetery 12 km away from Mogilev and executed.5

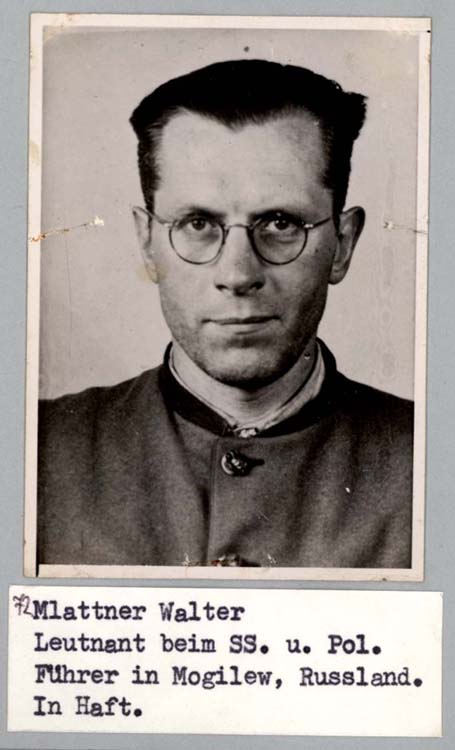

Walter Mattner, a policeman who took part in the murder of the Jews during this first action, described the shooting and how he felt about it in a letter to his wife:

[When we shot the Jews brought by] the first truck my hand trembled somewhat during the shooting, but one gets used to it. By the tenth truck I was already aiming steadily and shooting accurately at the many women, children, and babies. I thought about the two infants that I have at home, to whom this gang would do exactly the same, if not ten times worse. The death we were according them was a short and beautiful one compared to the hellish sufferings of the many thousands in the torture chambers of the [Soviet] GPU. […] Let's get rid of this brood [of Jews], who pushed all of Europe into war and is now agitating America also until it too is dragged into the war. […] I’m already looking forward to it, and many here are saying that when we return home, then it’s the turn of our local Jews.6

As historian Christopher Browning points out, Mattner desired to justify the murder of children and babies. These innocent victims couldn’t be accused of resistance to the regime or of collaboration with the Bolsheviks and they certainly didn’t die a “short and beautiful death.”7 He rationalizes the murder of Jewish children by the “need” to protect his own children.

Before their execution the Jews were first concentrated at the Dimitrov factory which was turned into a labor camp. A small number of Jews survived. Lyubov Naymark, one of the survivors, testifies:

In the autumn of 1941, when it was already very cold outside, Germans came into the ghetto in several trucks covered by tarpaulins. They started to drive the Jews out of their houses and to load them onto the trucks. The sounds of screams and weeping were heard in the ghetto. Those unable to walk were shot on the spot. I saw this with my own eyes. The Germans took away all the Jews; at the time I did not know where. Only later did I understand that it was to kill us. The group I was in, however, was taken to the camp located on the territory of the Dimitrov factory, where the "Strommashina" plant is today. At the camp I approached a German and told him that I was Russian [although she was, in fact, Jewish] but my husband was a Jew. He let me go, together with my daughter. That was about the next morning. In the camp my daughter saw some men, including my husband, sitting in a room, where Germans were beating them on the head with sticks.8

A second action took place two weeks later on October 19th9 as described in the report of the Einsatzgruppen written on the day following the murder:

On October 19, 1941, a large-scale operation against the Jews was carried out in Mogilev with the aid of the Police Regiment “Center.” 3,726 Jews of both sexes and all ages were liquidated by this action [...] On October 23, 1941, to prevent further acts of sabotage and to combat the partisans, a further number of Jews from Mogilev and surrounding area, 239 of both sexes, were liquidated.10

The Jews were routinely accused by the Germans of partisan activity and of resistance to the German regime, as will be discussed in the next section. By doing so the Germans legitimized the initial murder of Jewish males immediately upon their invasion of the Soviet Union. It quickly became a common excuse to legitimize the murder of Jews of all sexes and ages.

The attempts to conceal the mass executions in the forests or fenced off areas were sloppy and the civil population soon became aware of what was happening and rumors began circulating. We can learn about what happened during the second action and about the events surrounding it from Ida Fishman (maiden name Arman 1927-2007)’s testimony who was 14 years old when the ghetto was liquidated:

They put all of us into an empty room of a factory (now the "Strommashina" plant). We spent a day or two there. It was so crowded that there was no place to lie down. There were thousands of people there. My brother continually asked for a drink. In the morning of October 22, 1941, at about 11, some covered trucks arrived. It was raining and the rain was mixed with snow. They forced the people, mainly the women, to undress. The Gestapo men hit the naked women on their backsides with whips and laughed. They looked for valuables hidden in our clothes. They pulled a gold ring off my mother's finger. At the beginning I asked Mother "Where are they taking us?" Then I started to cry: "Mother, they will shoot us! Mother, I don't want to die!". When they took us to the pits, it was crystal clear where they had taken us and why. Mother whispered in my ear: "Tell them you are not Jewish, that your are Russian, and got into this truck by accident. Tell them your name is Nina. Tell them you are Belarusian and were living in our apartment." She approached the SS-men and started to explain: "This girl got into the truck by accident. She was living in our apartment and ended up in the ghetto by accident. She is not my daughter." The translator said [to me]: "Say the word "kukuruza." I said it. No one in our family spoke with a guttural pronunciation [speaking that way was considered to be a typically Jewish trait], everybody spoke clearly. They put me aside. Mother tried to also save my little brother. My sister looked Jewish but my brother didn't. Mother said [that] no one knew whose son he was. The translator said to him: "Drop your pants." They pulled down his pants and started to laugh loudly. Like all Jewish males, my little brother was circumcised [...]. As for me, they... threw me into a truck, took me back to Mogilev, and threw me out there.11

Following the mass murders that occurred during the two actions, the ghetto was liquidated and the area was restored to the city’s jurisdiction.12 The houses of the Jews were expropriated by the German government and sold to the local residents. Some 300 apartments were sold from the end of 1941 till the spring of 1942 . The theft and robbery of the Jewish property were legitimized by a committee under the auspices of the Mogilev mayor:

“November 20-21, 1941. A committee composed of the city engineer […], director of the housing department […], and representative of the financial department […], assessed upon the mayor’s instruction […] the value of the houses that had formerly belonged to the Jews and following the order of Feldkommandantura were offered for sale to the Russian residents of Mogilev.”13

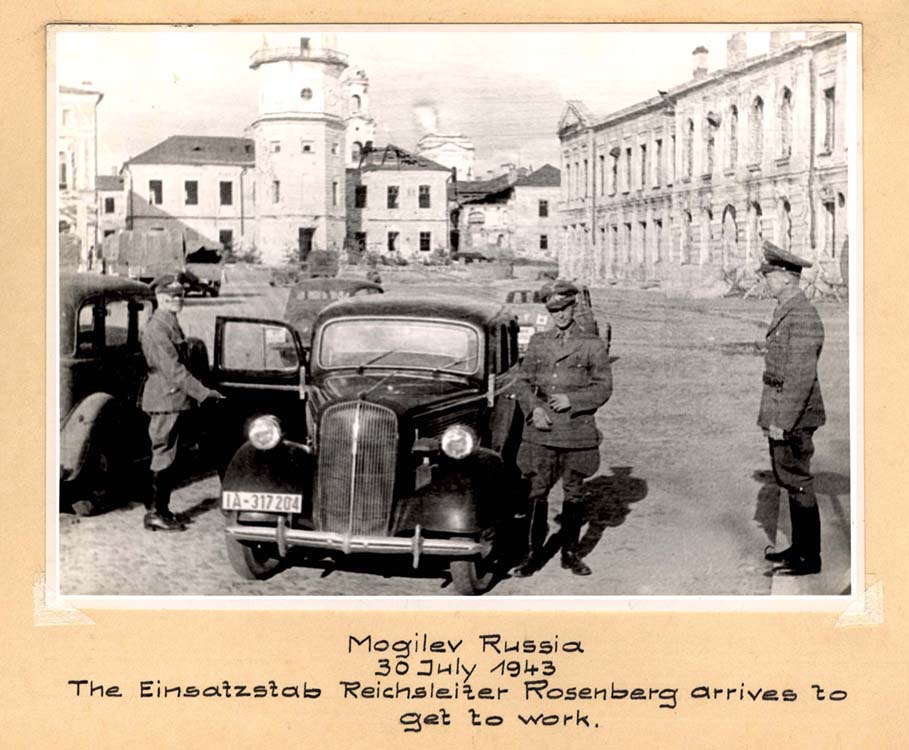

Germany was not content with robbing the immovable property of the Jews. Representatives of the Operational Staff Rosenberg also arrived in the city to confiscate Jewish cultural property.14

After the liquidation of the ghetto there still remained mixed families in which a Jewish spouse was married to a non-Jewish one. These families were arrested by the local police along with their children. We read in some testimonies that the Jewish spouses were executed along with their children while their non-Jewish spouses remained alive. Some testified about the fate of their families at trials conducted after the war.15

There also remained about 1,000 Jews still alive and imprisoned at the Dimitrov labor camp.16 The camp was set up on September 29th under the command of Bach-Zelewski and Jewish prisoners constituted a substantial share of the total number of forced labor there. Already in the beginning of October the Jews were banned from any employment in Mogilev except for the forced labor at the Dimitrov camp. At any given time of its existence, there were some 1,000-4,000 forced workers kept at the camp in deplorable conditions. Due to high mortality and ongoing executions, more forced workers were arriving – many of them Jews from nearby Slonim, Gomel, Briansk, Orel and other places.

A truck full of prisoners would leave the camp on Thursdays and the prisoners would be executed in the vicinity of nearby villages. In addition to the shootings that became routine at Dimitrov, the prisoners were being gassed on a large-scale. “The total number of civilians murdered there has been estimated at 25-30,000 by a German policeman and by Soviet local authorities, but this figure might be too high. It is certain that about 7,500 victims were Jews and 1,200 mentally ill people from the city of Mogilev.”17 As will be elaborated in the next section, Dimitrov camp was intended to be an extermination camp but the plan was eventually discarded. The camp was dismantled in September 1943 prior to the withdrawal of the Germans and the corpses of the prisoners were burned to destroy evidence. Some 500 survivors were transported to Minsk and Lublin, over half of them being Jewish.18

In the context of the brutal mass murders perpetrated in Mogilev, we should mention the Mogilev underground that consisted of 55 members including 22 Jews. All of its members were executed as well. The Jews are said to have “acted with fervent zeal to strengthen the organization.”19 Lastly, some 1,500-1,650 Jewish partisans were active in the Mogilev forests and hundreds of Jews in the Mogilev region were able to survive in the forests.The city was liberated by the Red Army on June 28th 1944.