Israel and Ida Rubin from Jaworzno and Four of their Six Children were Murdered in Auschwitz

Israel and Ida Rubin from Jaworzno and Four of their Six Children were Murdered in Auschwitz

In the course of an Aktion perpetrated in Jaworzno, Poland, in 1942, Israel and Ida Rubin and their son Tulek were deported to their deaths at Auschwitz. One year later, in the summer of 1943, Israel and Ida's daughters – Mila, Bronia, Rutka and Macia – were deported from the Sosnowiec ghetto to Auschwitz. Rutka and Macia were murdered in the gas chambers on arrival. Mila and Bronia passed the selection and were imprisoned in the camp. Mila was murdered several months later; Bronia survived Auschwitz and other camps. Her brother Mendek also survived.

The names Israel, Ida, Mila, Tulek, Rutka and Macia Rubin are documented in the Book of Names, six of the 4,800,000 names of Holocaust victims that have been collected by Yad Vashem and are commemorated in this monumental installation. This is their story.

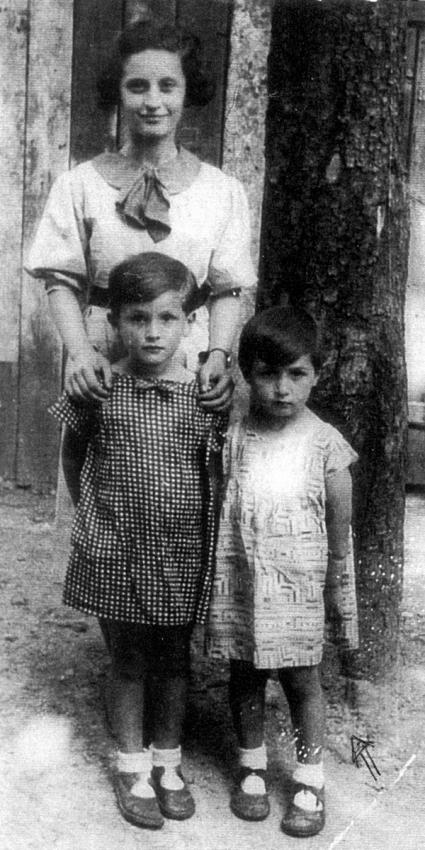

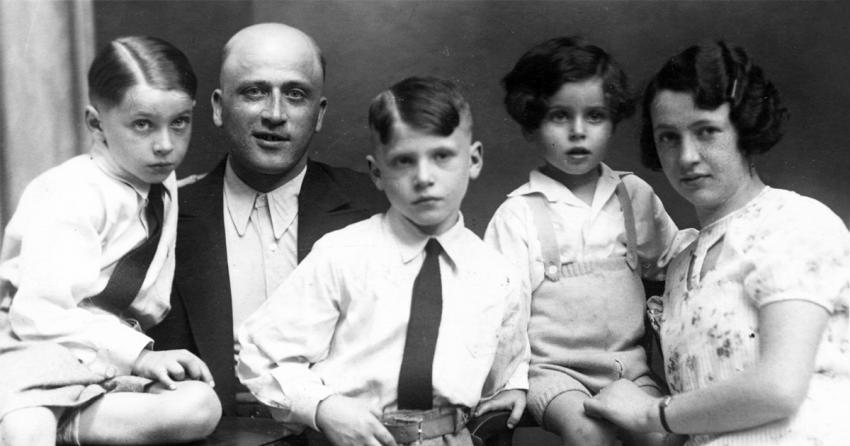

Bronia Rubin was born in 1931 in Jaworzno, the fourth child of Israel and Ida (née Mandelbaum). She had five siblings: Mila (b. 1923), Mendek (b. 1924), Naftali-Tulek (b. 1929), Rutka (b. 1933) and Macia (b. 1938).

Bronia was eight years old when World War II broke out. In an attempt to protect the family from the German onslaught, Israel sent Ida and five of the children to Mielec, to stay with family members. Israel remained in Jaworzno with his eldest son, Mendek, to mind the family store. "On the very first night, when the Germans marched into Mielec, we heard their booming, threatening voices – just to hear those voices made your blood curdle. We knew that life would never be the same," Bronia recalls.

Bronia remembers the utter hatred and antisemitism they experienced, the slurs and insults the invading army used when referring to the Jews of Mielec, and how they were so brutally treated: "When the Germans marched into Mielec, they burst into the homes of the Jews and made us go out in our nightgowns. That night, many of the men were marched to the synagogue and burned alive." After a while, her mother and siblings returned home to Jaworzno. At that point, Bronia remarks, "even though I was still only a child, I had to grow up very quickly."

At first, Bronia and her family were able to stay in their home, but their store was confiscated along with all of their money. Bronia was forced to smuggle goods her father could sell on the black market in order to buy some basic provisions:

I would cover up my "Jewish" armband with a big shawl and go on my mission. Every time I went out, I was almost certain I wouldn't return home. I could have been shot, but not before I would have been tortured to reveal the names of my network contacts.

At the beginning of the war, daily life was difficult, because one never knew what was going to happen. Often you had to make split-second decisions, and you didn't always make the right choice. We could never have prepared for the challenges that would come.

In 1942, there was an Aktion in the town, and Bronia, her brother Tulek, and her parents were taken to the synagogue to be deported. Her other siblings reached their hiding places in time. In a moment of desperation, Bronia's mother told her to run. "If I had been caught running away I would have been shot right in front of her, but that was the risk she took." Instead of running, Bronia decided to inch her way slowly out of the synagogue, and escaped to a dairy farm, where she begged to be hidden until nightfall.

Realizing that her parents and brother were not likely to return, like all the other Jews who were taken, Bronia and her sisters decided to flee to Sosnowiec, a town nearby where they heard there were still Jews. "None of us mourned that our parents were certainly going to be murdered. I think that that was the moment when something inside of us died. We couldn't grieve because we ourselves were dealing with the unknown." In Sosnowiec, they were sent to live in the ghetto. There, Bronia continued to smuggle food for her siblings, now orphans. In the summer of 1943, the Nazis began to liquidate the Sosnowiec ghetto. The residents were rounded up and sent away, never to be heard of again.

Despite their efforts to hide, Bronia and her eldest sister Mila, whom she worshiped, were discovered during one of the Aktionen and deported to Auschwitz. "We knew we were being taken to our deaths and no one said a word," Bronia recalls of the harrowing train ride to the extermination camp. "Schnell, schnell, schnell! This is how we were greeted upon our arrival at Auschwitz. We were told to leave all our belongings behind. We were terrified and powerless." At the selection, Mila was directed to the right while Bronia and her sisters were told to go to the left. "In another split-second decision I decided to run to the line where Mila stood. I was also jeopardizing Mila's life, having a young twelve-year-old girl next to her, but it was too late."

Bronia and Mila were taken to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where they were stripped naked, their hair shaven and arms tattooed with their prisoner numbers. Bronia was given a prisoner dress, a pair of wooden clogs and an equally valuable possession, a tin bowl attached to a rope. The sisters were assigned together to one of the barracks. Bronia recalls:

There was no typical day in Auschwitz, but it always began by being woken up very early in the morning... so I can't tell you exactly what time. Once up, we were made to stand for roll call sometimes for hours on end, in the cold and the heat, until everyone was accounted for. After roll call, the prisoners were marched to forced labor. Work was not meant to be productive in Auschwitz. Work was designed to kill.

How can I describe being hungry for two years? What we got could not be considered food or eating. What we consumed was meant to keep us barely alive another day. In addition to the constant hunger and fear of death, we had to deal with plagues of lice. Our bodies were one big scab from scratching all the time. As a result of these subhuman living conditions, disease ran rampant throughout the camp.

Mila came down with typhus and was sent to the infirmary. "This presented me with a huge dilemma. Everyone in the camp knew that going to those barracks was a one-way ticket to the gas chambers. On the one hand, I knew I shouldn't go with Mila, but on the other, I didn't know how I could part from her, either." Despite the risk, Bronia chose to go with her sister to the infirmary.

"One day, the head nurse, a woman named Bozenka, told me that the next day all of the infirm were going to be taken to the gas chambers," Bronia recalls. "That nurse risked her life in order to save mine. I just upped and left my sister, never even saying goodbye. I didn't know how to face her. Afterwards, I felt so guilty not going with Mila that I believed I didn’t deserve to live." The next day, Mila was murdered. Her loss nearly broke Bronia. Bronia soon came down with typhus, too, and Bozenka cared for her even when the young girl was in a coma for nearly a month.

Bronia remained at Auschwitz until January 1945, when she was forced on a death march. Still weak from typhus, Bronia was supported by Bozenka on the march to the Ravensbrück concentration camp. A few days later, Bozenka and Bronia were forced onward to the Neustadt-Glewe camp. There, they were liberated by the Red Army at the beginning of May 1945. Sadly, Bronia recalls liberation as the worst time of her life. "For the first time in five years, I had the 'luxury' to think and feel, and as far as I knew, I was alone in the world."

Bronia discovered that her brother, Mendek, survived against all the odds.

Mendek and Bronia immigrated to the United States in 1950. Bronia married Ephraim Brandman, with whom she had two daughters and built a family life in the Borough Park neighborhood of Brooklyn, NY.

For fifty years, Bronia Rubin-Brandman didn't talk about her wartime nightmare, refusing to tell her family what she had endured during the Holocaust. All that would change in the 1990s, when she began volunteering at the New York Museum of Jewish Heritage and one of the visitors noticed the tattoo on her arm. Finally, after fifty years of lonely heartache, the silence ended. Bronia begin to tell the harrowing story of how she and her older brother, Mendek, were the only members of her immediate family to survive. Thirty years later, at the age of 92, she still tells her story, working tirelessly to ensure that people all over the world know of the unprecedented atrocities of the Shoah.

In 2005 and 2011 Bronia submitted 34 Pages of Testimony to Yad Vashem bearing the names of her beloved family members who were murdered during the Holocaust; names that are commemorated in Yad Vashem's Book of Names.

The Holocaust touches me in a very deep way, because I lived it. For fifty years, I didn't speak about my experiences, and for 25 years, I could not laugh. The Nazis left me without any tears; the enormity of the devastation, of the deliberate and planned murder of six million innocent people, among them 1.5 million children, was too much to bear. The fact that there is a Book of Names of so many of these victims ensures that when the last Holocaust survivor dies, our story will remain for humanity to know and remember. The Book will continue to be a testimony to our lives as survivors, as well as to the victims – who lived and breathed like my parents, siblings, aunts, uncles and cousins did. Each of them had their own unique identity, talents, challenges and dreams. Each one is an entire world, forever lost.

(Bronia Rubin-Brandman)