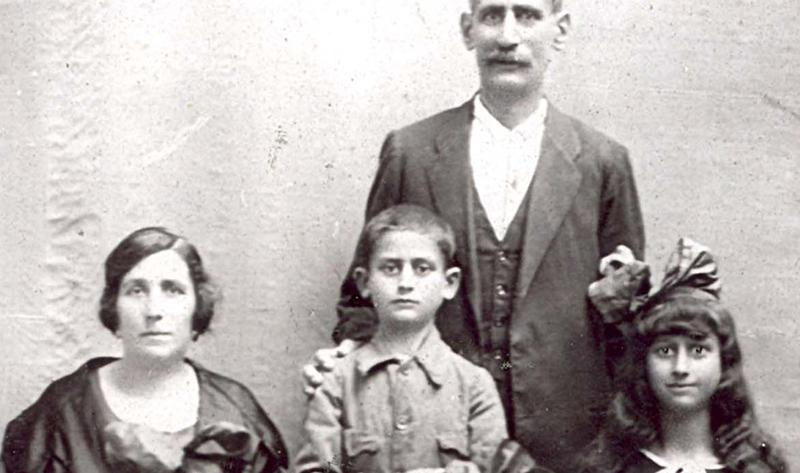

The Hasson Family from Rhodes

3 August 1944: The Last Deportation of Jews from Greece

On 3 August 1944, approximately 2,500 Jews were deported from Athens on cattle cars, most of them from the island of Rhodes. After thirteen tortuous days, the deportees reached Auschwitz-Birkenau. This transport was the last deportation of Greek Jews. Sylvia Hasson (later Berro) and her family were among the deportees.

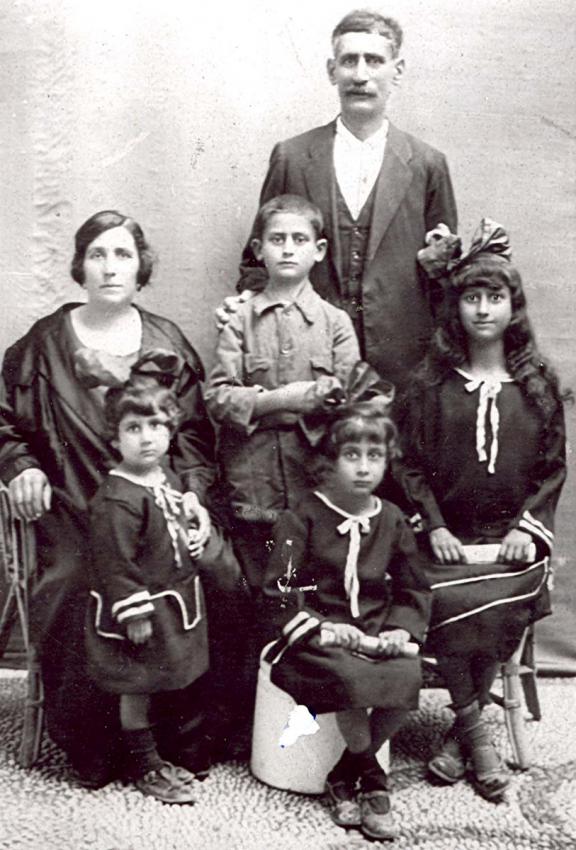

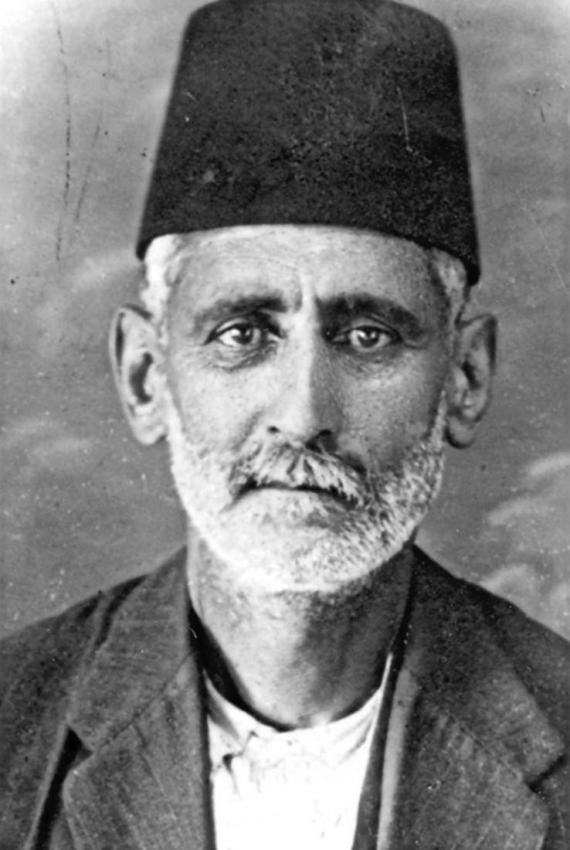

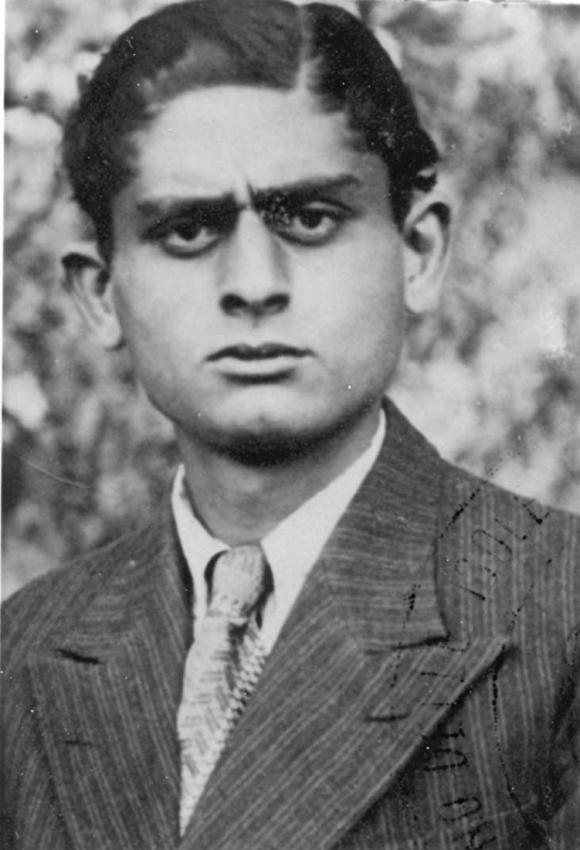

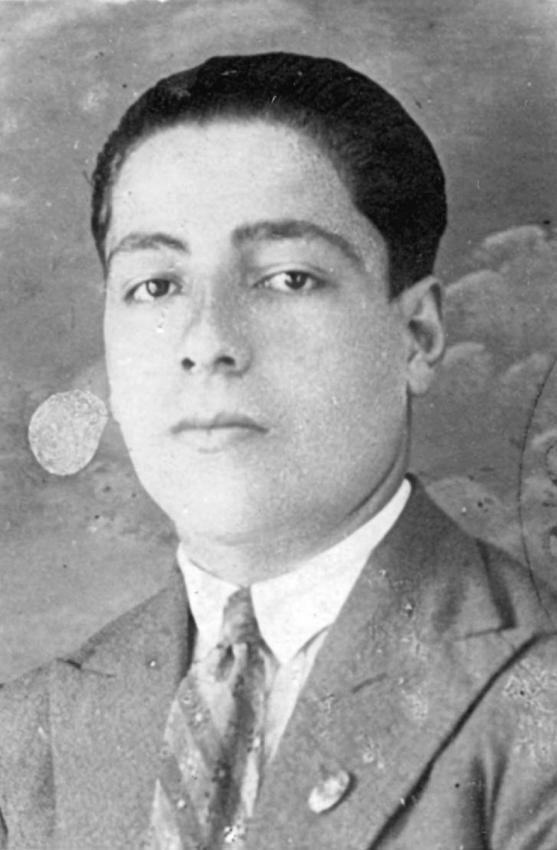

Sylvia was born in 1920 in Rhodes, Italy (today Greece), the youngest daughter of Ruben-Reuven and Mazaltov Hasson. She had six brothers and sisters: Albert, Caden, Signorou, Vida, Victor-Vittorio and Bellina-Boulie. Two more of Ruben and Mazaltov's children died in infancy. The family led a traditional Jewish lifestyle, and were comfortably off. Ruben Hasson had a grocery store, and Mazaltov was a housewife. They were first cousins. The Hasson family had lived in Rhodes for generations, and Sylvia and her siblings grew up surrounded by dozens of relatives. In 1920, Albert and his maternal uncle, Nissim Hasson, immigrated to the US. Nissim later returned to Rhodes, while Albert settled in Seattle. In 1928, Caden fell ill, and died five days later. "From that day on," relates Sylvia, "I didn't see Mother smile. Although there were still four of us girls, the pain overwhelmed her." Signorou married Salomon Hasson. In 1938, their daughter Regina was born, followed by their son Giacobbe-Jaco in 1943. That same year, Mazaltov passed away at home in Rhodes.

On 15 September 1943, the Germans conquered the Italian island of Rhodes, and on 3 October, they took the adjacent island of Kos from the British. Until July 1944, no steps were taken against the Jews of Rhodes and Kos. On 20 July 1944, the Germans ordered the Jewish men of Rhodes from ages 18 and up to report to the headquarters of the Italian Air Force officers, which then served as Gestapo headquarters. They were told to bring their ID cards and work permits, as they would be recruited for the German war effort. Everyone who followed the order to report, did not return home. The next day, the Germans ordered the women and children to join the men, and to bring ID cards, food supplies for ten days, and their valuables. By 21 July, all the Jews had been arrested and their property confiscated, except for those with Turkish citizenship. The Turkish Consul General in Rhodes, Selahattin Ülkümen, later recognized as Righteous Among the Nations, saved dozens of Jews with Turkish citizenship from Rhodes and Kos. Sylvia relates:

They rounded us up… first of all my father and brother, and the next day, also my sisters and I… Included among the detainees were my married sister Signorou, her husband Salomon and their two children, a five-year-old girl and a one-year-old boy, my uncles, aunts and cousins, too many to cite their names… We had nowhere to hide. They concentrated us all in the Aeronautica building… Someone made a speech in Spanish and said: "Anyone who has jewelry has to hand it over," and we had to hand it all over that day. I don't know how many sacks of jewelry and rings were taken that day.

The Jews of Rhodes were detained in appalling conditions. On the afternoon of Sunday, 23 July, the deportation of the Jews began. Approximately 1,700 men, women and children were led out of the Aeronautica building to the island's port via the city center, which was empty on account of the curfew that had been imposed on the residents. Upon arrival at the port, they were loaded onto three old open boats. On the way, the boats stopped at Leros port, where they picked up the only Jew living on the island, Daniel Rahamim. The same day, the Gestapo rounded up the Jews of Kos within three hours, some 100 people, and housed them in two rooms inside the governor's palace. Their property and warehouses were appropriated. The next day, they boarded a small ship, which stopped by the island of Kalimnos in order to pick up the one Jew who lived there. The ship from Kos also reached Leros, at which point the passengers were loaded onto the boats that had arrived from Rhodes. They stayed there for about four days. The boats were in Samos for a further day, and on 31 July, they reached the port of Piraeus in Athens.

The journey from Rhodes to Piraeus lasted around ten days in horrific conditions. The heat was unbearable, no food or water was distributed, and the boats were so full that the detainees could not make the slightest move. Seven people died during the voyage and their bodies were thrown into the sea.

From Piraeus they were immediately transported by truck to the Haidari concentration camp adjacent to Athens, where they suffered all manner of humiliation and hardship. The men, women and children were separated. Any valuables still in their possession were confiscated. They only received a little food from the Red Cross after 36 hours.

After 2-3 days they were ordered into trucks and transferred to the Athens Rouf railway station. There, under threat of arms, the women were separated from the men and ordered to board cattle cars. During the interminable journey to Poland, which lasted some 13 days, the deportees endured starvation and intense humiliation in rail cars that carried at least 65 persons. Each wagon had only one small window covered with a grid and two buckets inside; one contained water and the other served as a toilet. There was no place to sit, and the wagons were so full that there was not even enough space to lie down. Most people travelled bent on their knees for days without knowing where they were headed. Deprived of food and water, around 100 persons died en route and were thrown into the fields along the railway line. The train stopped several times. Sylvia relates:

Our only food ration consisted of two lemons, a crust of bread and a mouthful of water during all this time… For the full ten-day journey, I had to sit on a little barrel in the windowless cattle wagon, with my knees doubled up under my chin… My family members were all in other cattle wagons. However, at one point the train stopped during the journey and my married sister, Signorou, got off the train and managed to see me to ask me a favor. I still remember hearing her last pitiful words to me, 'Have you got a lemon for me to make lemonade to give to the children?' Regina was five years old, and Jaco turned one on the train journey." (Hasson-Berro Sylvia, The Story of a Survivor, 2000, p. 53)

The deportees arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau on August 16. According to historian Danuta Czech, there were approximately 2,500 Jews on this transport (Czech, Auschwitz Chronicle 1939-1945, 1990, p. 688). Upon arrival, the men and women were separated, and underwent a selection. Some 1,900 people were sent straight to the gas chambers, while the remaining deportees became camp inmates and had prisoner numbers tattooed on their arms. 346 men were tattooed with numbers B7159-B7504 and 254 women were tattooed with numbers A24215-A24468. A day before the train arrived in Auschwitz, on 15 August, Sylvia "celebrated" her 24th birthday. She relates:

Upon arrival at Auschwitz, the German guards took away our small cases filled to overflowing with our personal belongings, including gold coins which had been sewn into the lining of our bed linen. We had even brought pots and pans with us, as we had no idea where we were being taken." (Hasson-Berro, p. 48)

On the second day after we arrived, the number A24369 was tattooed on my arm. From then on, that is how we were addressed. I was "dreihundertneunundsechzig vierundzwanzig" – no longer a name, just a number. They distributed clothes such that a tall woman received a small dress and vice versa. You could also get a pair of shoes that were mismatched in size.

Sylvia was transferred together with other women to "Karantina", the quarantine block where prisoners who had just arrived at Birkenau were taken. Sylvia's father Ruben, her sister Signorou and her children were murdered on arrival. Her brother Vittorio, her sisters Vida and Bellina and her brother-in-law Salomon, Signorou's husband, passed the selection. "On Yom Kippur, my brother-in-law told me that my brother had died a few days before Rosh Hashanah [18 September 1944]," relates Sylvia. "'Don't worry, my child,' he said, 'The war will be over soon.'"

"The Polish winter," recalled Sylvia, "Was unbearable for us. On one occasion, I exchanged a few portions of food for a coat." (Hasson-Berro, p. 55). Sylvia was assigned to forced labor carrying bricks.

In late October 1944, Sylvia and another approximately 100 female Jewish prisoners were transferred from Auschwitz to forced labor in the Wilischthal camp, a subcamp of the Flossenbürg concentration camp. Sylvia and her friends worked there manufacturing weapons parts. On 13 April 1945, with the approach of the Allied armies, Sylvia and her fellow prisoners were evacuated to the Terezin ghetto. On 8 May 1945, the Terezin ghetto was liberated by the Red Army.

"I stayed alive," says Sylvia, "Because I am a very optimistic person. When I was in the camps, I never said, 'I'm going to die here.' I ate everything they gave me in order to stay alive. I never said it was good or bad. That's also part of my character. I have the will to survive." After liberation, Sylvia discovered to her devastation that she was the sole survivor of her family. Survivors from Rhodes told her that her sister Bellina was last seen around 15 January 1945 in the Ravensbrück concentration camp, after which she vanished without a trace. Her brother-in-law Salomon was also murdered. Sylvia returned to Italy, and then travelled to the US, to her brother Albert. From there, she immigrated to South Africa. In 1949, she married Asael Berro, whose family she knew from Rhodes, and they had two daughters.

In 1991, Sylvia Hasson-Berro submitted Pages of Testimony to Yad Vashem in memory of her father Ruben, her brother Victor, her sisters Bellina-Boulie, Vida and Signorou, her niece Regina and her nephew Jaco, and dozens more relatives, all of whom were deported from Rhodes and murdered. Her memoir, "The Story of a Survivor: The Memoirs of Sylvia Hasson-Berro" was published in 2000.