Kurt Gerron - Successful Jewish Actor and Director in Germany between the World Wars

28 October 1944: Deportation of Jews from Terezin to Auschwitz

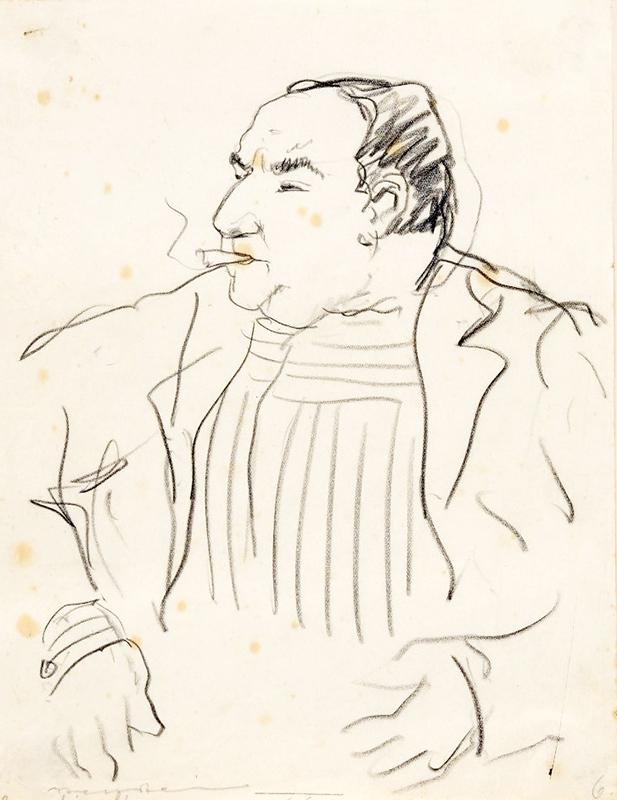

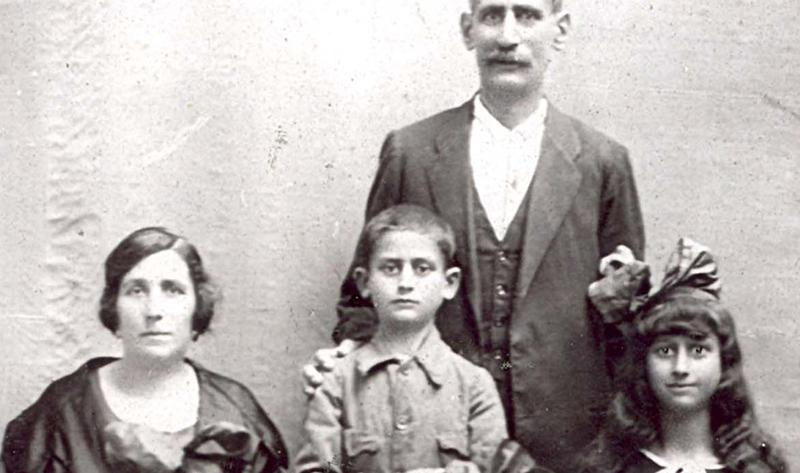

Born Kurt Gerson in 1897 in Berlin, Kurt Gerron was the only child of Max and Toni née Riese. His father managed a thriving clothing business, and his mother was a housewife who took care of her son's education. Gerron enlisted in the German Army in World War I, was badly injured twice, and was released from active service at the front. He started studying medicine, and after two years, re-enlisted as a doctor. After the war he completed his studies, but a year later, decided to devote himself to acting. His first performance was in the cast of the cabaret, "Kuka" in Berlin. In 1921, he joined the Wilden Buhne ("Wild Stage") cabaret troupe, the first of several cabaret troupes that he worked with, and in 1924 he married Olga-Olly née Meyer. Gerron performed in Max Reinhardt's theater in Berlin, at the same time starring in silent movies. He also successfully transitioned to talking films. In 1928, he appeared in the role of "Tiger" Brown at the premiere of the musical drama, "The Threepenny Opera" by Berthold Brecht and Kurt Weill in Berlin. The show was a huge success, and the song, "Mack the Knife", sung by Gerron, became a big hit. In 1930, Gerron appeared alongside Marlene Dietrich in the film, "Blue Angel" in the role of Kiepert the magician. By 1933, he had appeared in dozens of movies and directed many more, and was one of Germany's most successful artists.

In January 1933, the Nazis rose to power in Germany. Shortly afterwards, thousands of Jews were ousted from the movie, entertainment, theater and music businesses, among them Kurt Gerron. At the time, Gerron was in the middle of directing the film, "Kind Ich Freu Mich Auf Dein Kommen" at UFA Studios in Berlin, and was also one of the scriptwriters. On 1 April 1933, the day of the national boycott on German Jewry, Gerron and his Jewish colleagues were thrown out of the studio. Actress Magda Schneider, present at the time, later recalled: "Every time Gerron's name is mentioned, I remember this scene… We were about to start filming when the production manager said that he wanted to say a few words about the boycott, and then he said: "All Jews, leave the studio." I only saw Gerron's shaking back as he left. He was crying." (Felsmann und Prümm, Kurt Gerron - Gefeiert und Gejagt, p. 63). The same month, Gerron left Germany and moved to Paris with his wife and parents, and some two years later, he moved to Vienna. In September 1935, he moved again, to the Netherlands, because of the rising antisemitism in Austria. He settled in Amsterdam, and continued to direct movies. In 1937, approximately four years after Gerron had left Germany, Gestapo headquarters in Lüneburg issued an order forbidding truck drivers from displaying pictures on their vehicles of Ernest Röhm and Jewish actors Kurt Gerron and Fritz Greenbaum, who were presumably still popular with the public.

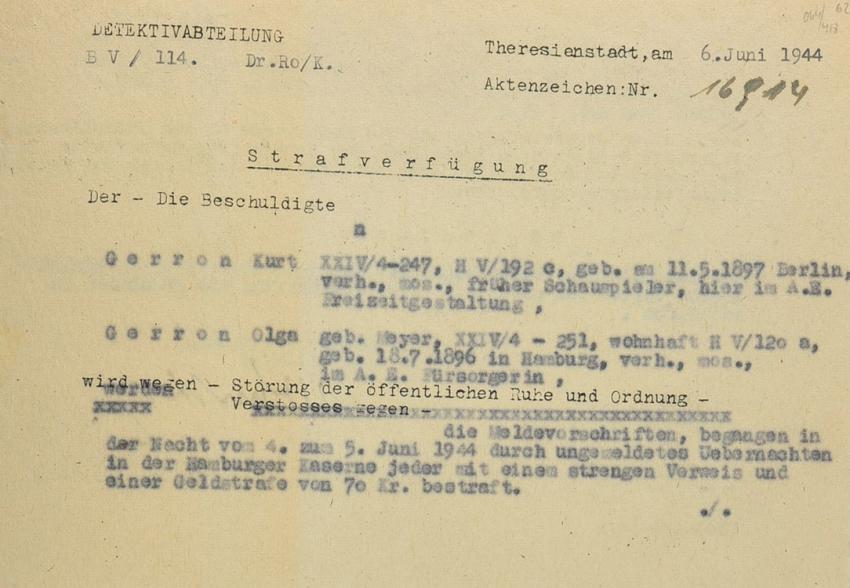

In May 1940, the Germans occupied the Netherlands. Gerron continued to work in his field under the Nazi regime in the Netherlands. In September 1943, he was arrested, and sent with his wife Olga to the concentration and transit camp, Westerbork in the northeastern part of the Netherlands, where he continued his cabaret activities. His parents were arrested even earlier, and on 4 May 1943, they were deported from Westerbork to their deaths in Sobibor. There were no survivors from that transport. On 25 February 1944, a deportation train left Westerbork for the Terezin ghetto. Kurt and Olga were among the deportees. In Terezin, Gerron established a cabaret troupe in German, and produced the review, "Karussell", with the participation of the "Ghetto Swingers".

The Red Cross Delegation's Visit to Terezin

In June 1944, a delegation of the International Red Cross visited the Terezin ghetto. A short time before the scheduled visit, thousands of Jews were deported to Auschwitz in order to alleviate the overcrowding in the ghetto. In advance of the visit, the pavements of the delegation's route were scrubbed, and a children's kindergarten was created, just for one day. Many of the prisoners who had been crammed into overcrowded rooms on the ground floors of houses along the scheduled route, were evicted, and in their stead, three delegates, two of them representatives of the Danish Red Cross, visited the "family rooms". They were only permitted to speak to well-connected prisoners – Danish Jews and representatives of the Jewish leadership, and only in the presence of the SS. The Red Cross delegates watched a football match and a children's opera, and listened to Verdi's Requiem, which director Rafael Schächter had decided to perform long before he knew about the plan to "beautify" the city. The deception succeeded beyond anyone's expectations. In the report written that evening by Dr. Moritz Resel, a representative of the Red Cross in Geneva, he described Terezin as "a city like any other", whose inhabitants received food rations even larger than those of the general population, and lacked nothing except for alcohol and cigarettes. The delegation saw Terezin as a final destination, and did not investigate the fate of the thousands of Jews who passed through Terezin on their way to the East.

In December 1943, the Germans decided to produce a propaganda film in Terezin, and gave a Jewish inmate by the name of Jindřich Weil the task of writing the script. On 20 January 1944, the arrival of a transport of Danish Jews and the welcome speech given by Paul Epstein, head of the Council of Elders in Terezin, were filmed, so that they could be incorporated in the film. The Germans restarted work on the film after the visit of the Red Cross delegation in June 1944. The news company "Aktualita" from Prague was tasked with production and filming, and this time, Kurt Gerron was ordered to write the script and head the Jewish production team. Gerron based his script on drafts written earlier by Weil. The filming started on 16 August 1944, and continued until 11 September 1944. During the filming, Karel Pečenẏ from "Aktualita" took over the production, and demoted Gerron to the role of assistant manager. Ghetto inmates were forced to participate in the film. Hundreds were ordered to play extras, while others were given specific roles. The filming was carried out under strict SS supervision. On 28 September 1944, before the movie was completed, the deportation of some 18,500 Jews from Terezin to Auschwitz began. The last transport from Terezin to Auschwitz departed on 28 October. Among the Jews on the last transport were Kurt Gerron and his wife, Olga. Most of the actors, extras and workers on the film were deported to Auschwitz in the course of the month of October. On 26 October, the deportees received an order to report the same evening to the Hamburg barracks, in preparation for deportation. They were allowed to bring a small amount of luggage.

Aliza Ehrmann (later Scheck) documented the events in Terezin from October 1944 until liberation in May 1945, in her diary:

28 October 1944

Boarding the cars. Orders. The last of the leaders are leaving, whole departments have been left completely empty. Where there were 100 before, now there are three people. All the kitchens are closed, except for two… Every visit to headquarters carries the risk of death, inhuman responsibility for the lives and deaths of thousands. 2,038 people, 50 or more in cattle cars. Günther [SS Officer Hans Günther] orders the last tiny windows to be sealed with tin, so that they should be transported without a drop of air or light for 24 hours, with one bucket for fifty people, and everything is too awful. I am utterly destroyed.

29 October 1944

The ghetto has been reorganized. The transports have stopped, for now.

Ada and Dr. Willy Levy were also deported from Terezin to Auschwitz. In her testimony, given in 1946, Ada relates:

On 28 October 1944, my husband and I were thrown into a cattle car that was too narrow to hold its passengers, and was immediately sealed… The appalling conditions on this transport, which lasted several days, led us to utter desperation and close to death. It seemed to us to be the ultimate form of suffering. Could anything be worse than this?... After this death journey into the total unknown, with no air, no water, no light, standing crammed together, sometimes among corpses, they took us off [the car] in the middle of the night. We didn't know where we were. SS men with whips received us… The women were immediately separated from the men, and though I hoped to still see my husband the next day, I tried to sneak one more look at my Willy in this terrifying atmosphere. I didn't understand that this would be the last time [that I would see him].

The deportees reached Auschwitz on 30 October. "We marched forward, the women, in pairs, and stood under a spotlight – right, left. I was directed to the left. We had to march at night on a dirt path. Trucks with our friends rolled past us," relates Ada. "We could hardly stand on our feet for pain and exhaustion. We didn't know that those standing on the trucks were being led to their deaths. No one saw or heard from them again."

The film "Theresienstadt – a Documentary Film of the Jewish Settlement " was completed in March 1945. The SS sent a team to the ghetto to tape excerpts and integrate them in the sound track, but the film was never screened for the general public. The lists that Gerron wrote and edited during the filming survived. The film itself vanished at the end of the war, and fragments came to light from time to time, but a complete copy does not exist. According to Terezin inmates, the film was ironically entitled, "The Führer Gives the Jews a City". Excerpts of the film are displayed in this exhibition.

In 1995, Gerald Ehrlich, Kurt and Olga Gerron's nephew, submitted Pages of Testimony to Yad Vashem in their memory.