The Rescue of the Mir Yeshiva

Among the Jewish refugees that arrived in Vilna were some 2,400 yeshiva students and their teachers, including those of the Mir Yeshiva. Their destitute conditions placed a great burden on the aid organizations of Vilna, which turned to outside help, including the Joint, which had been collecting donations from American Jews since WWI and dividing it among needy Jewry. After they received information on the yeshiva refugees of the town, leaders of Orthodox Jewry in the US established a special organization to raise funds to save the rabbis and yeshiva students – "The Rescue Committee of the Organization of US Rabbis".

In the summer of 1940, the possibility of leaving Lithuania began to become more real: in Kovno, Jan Zwartendijk, issued entrance permits to Curaçao, an island in the Caribbean Sea under Dutch authority. The Japanese consul in Kovno, Sempo Sugihara, provided those refugees with permits legal passage via Japan. This route necessitated visas to pass through the USSR. However, before those who held visas could leave, Lithuania lost its independence and became a Soviet republic, and the authorities closed down the foreign missions working there.

A Jewish delegation headed by Zerach Warhaftig, head of the Israeli National Committee to Save Polish Jewry, turned to the Russians for permission to secure the exit of the Jewish refugees from Poland. In August 1940 he received a positive reply from Moscow. Until May 1941, the Soviets permitted the exit of Jewish refugees from Lithuania.

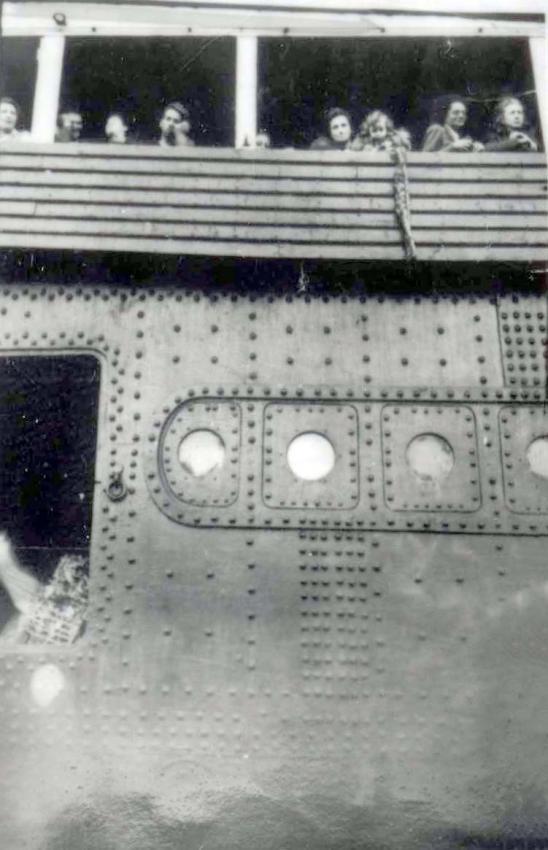

The refugees managed to leave Lithuania thanks to the response of the Japanese consul Sugihara, the Dutch consul, Zwartendijk, and the British consul Gant, who provided entry visas to Eretz Israel. Some 2,200 refugees – including students and rabbis of the Mir Yeshiva – arrived in or passed through Japan. The Mir Yeshiva was the only yeshiva that managed to leave Lithuania in its entirety. Hundreds of students from other yeshivas also traveled to Japan, despite the objection in principle to them leaving by the heads of their yeshivas.

After Vilna became part of independent Lithuania, the yeshiva stationed itself in Kédainai, and after Lithuania was annexed to the Soviet Union its members were ordered to leave Kédainai as it was now proclaimed a regional city. The yeshiva broke up into four groups that settled in Shat, Kroki, Krekenava and Ramygala. It operated in these new locations without official permission, but the authorities turned a blind eye, the Torah lessons continued almost as normal, and the yeshiva heads were able to ensure the subsistence of their students.

"Between the members of the Mir Yeshiva and other refugees that also received permission to leave Russia, we received permits not only for Curaçao but also for entry to the United States as well as emigration to Eretz Israel. Rabbi Finkel – the Rosh Yeshiva – and his family received permits to emigrate to Eretz Israel, and because of this they also were given exit permits from Russia".

Testimony of Rabbi Chaim Shmuelevitz and his wife Miriam, Yad Vashem Archives, 0.3/30304

Mir Yeshiva members Yaakov Ederman, Eliezer Portnoi and Moshe Zufnik took charge of the arrangements for the yeshiva to leave Lithuania, with the assistance of Zerach Warhaftig. Every person leaving had to present himself to the NKVD (the Soviet Secret Service) in Vilna or Kovno for a formal investigation before receiving his exit visa. Dozens were rejected and held back in Lithuania. It is unknown whether any survived.

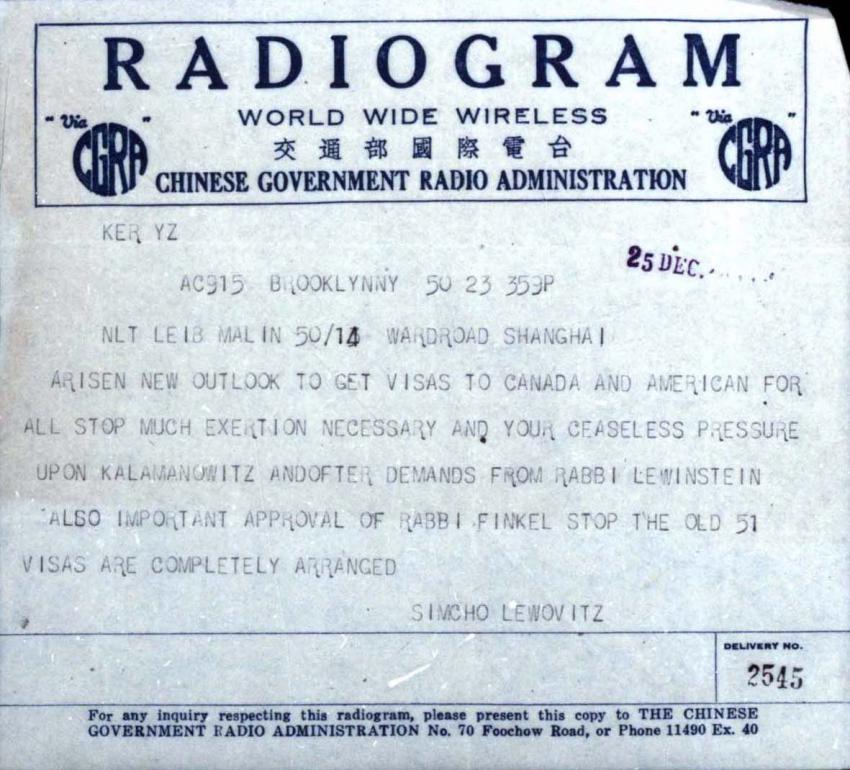

The rest of the yeshiva students and teachers left in groups of 50 for Japan. From January 1941, five or six groups of yeshiva students left from Vilna to Vladivostok, and from there to the Japanese port city of Kobe, where hundreds of refugees were gathered. Payment for the visa to the USSR, 180 dollars per person, was provided by the Joint. "The Curaçao travelers" were unable to continue, as it became clear that the visas they had received were not valid. Those with permits to the US continued their journey. While in Japan, Rabbi Chaim Shmuelevitz received a permit for him and his family to enter the US – but he waived it in order to stay with his students in Japan.

Even in its new Japanese exile, the yeshiva continued its studies. Assistance arrived from the Joint, the "Rescue Committee" in Switzerland and via Jewish institutions in Argentina. After some time, the Japanese moved the yeshiva and its members, together with other Jewish refugees, from Kobe to Shanghai, which was under their control.

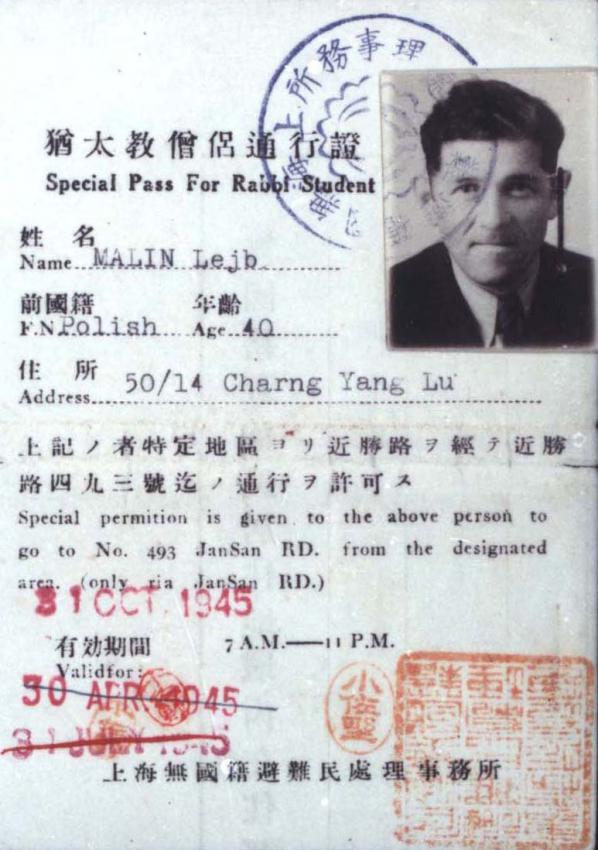

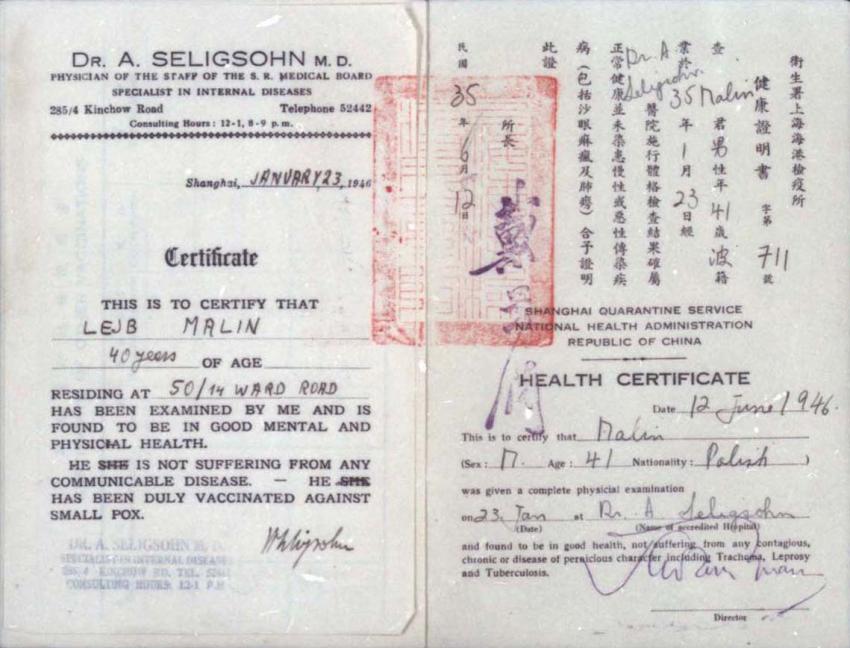

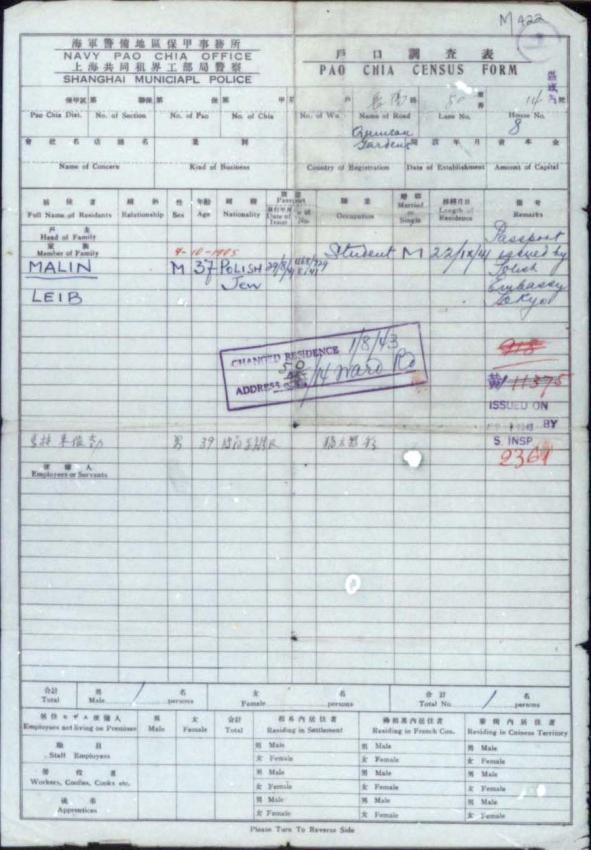

In 1943, all the Jewish refugees and foreign residents that had arrived in Shanghai after 1937, including members of the yeshiva, were forced into a ghetto. Ghetto residents received passports marked with a yellow line, but they were not ordered to wear any signs distinguishing them as Jews. Aside from the demarcation of their permitted living area, no other limitations were placed upon them, and they were allowed to travel outside of the ghetto to see to their needs.

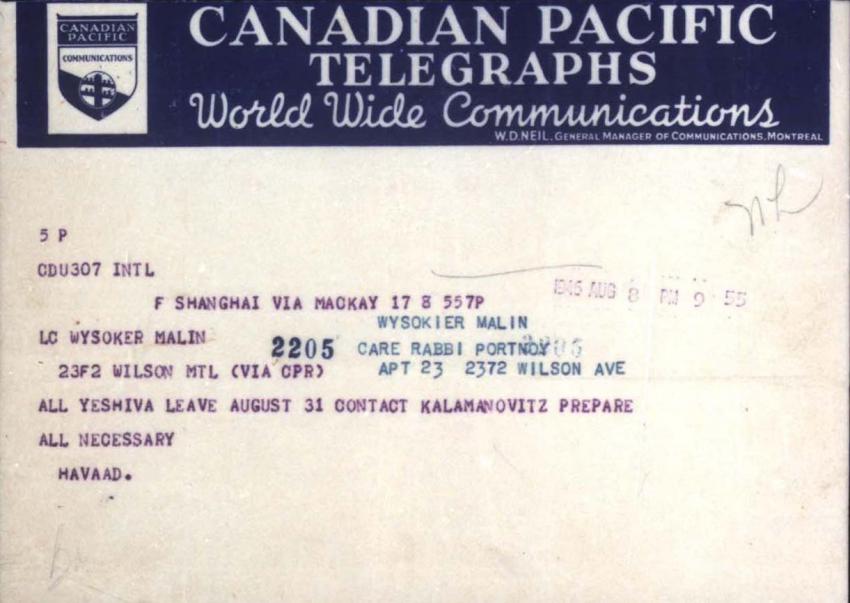

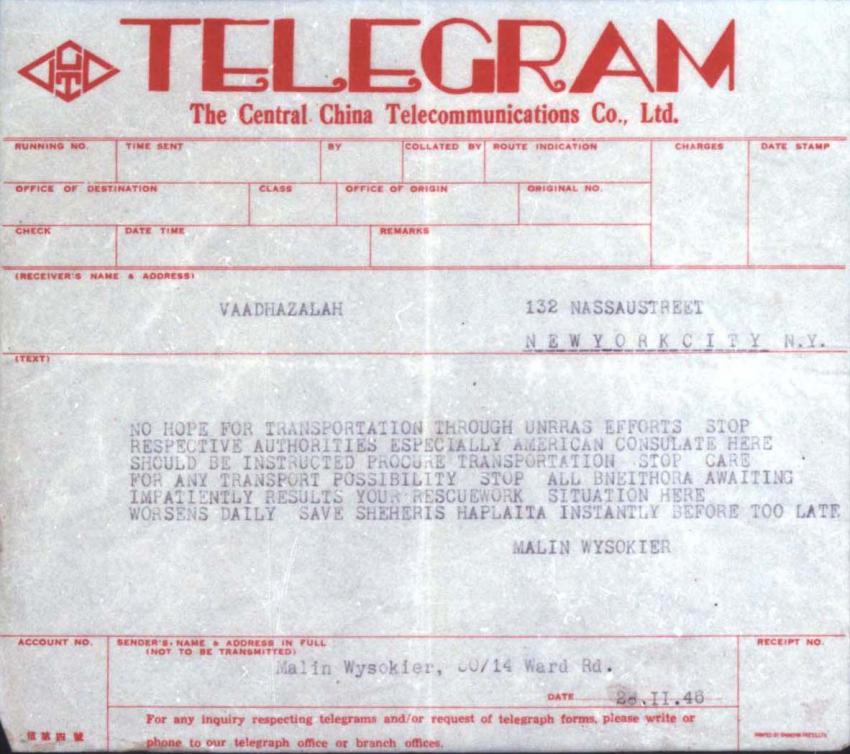

Following the surrender of Japan in August 1945, leaving Shanghai became impossible because of transportation problems. Small groups of people managed to leave, but most of the yeshiva members were forced to stay until the end of 1946. The majority of them then left for the US, where the yeshiva split. Some of the students remained in the US and established their yeshiva in Brooklyn, known as Mirer Yeshiva, while others left for Eretz Israel with Rabbi Shmuelowicz, where they established the Mir Yeshiva in the Beit Yisrael neighborhood in Jerusalem, known as Yeshivas Mir Yerushalayim.