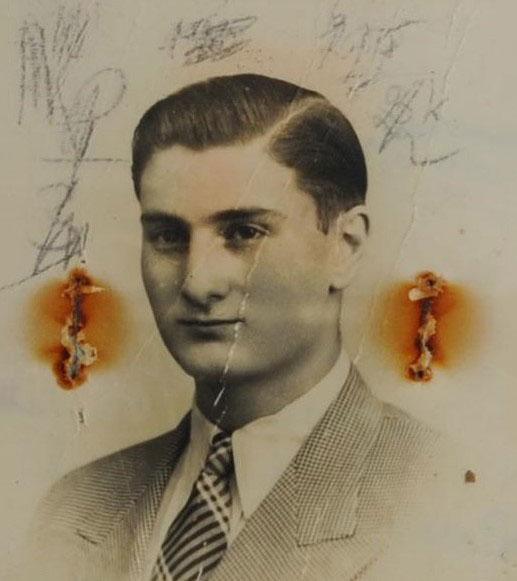

David Stoliar was born in October 1922 in Kishinev, Romania, to Yaakov and Bella née Leichiman. His parents divorced when David was ten, and he moved to France with his mother. In 1937, he returned to Romania and lived with his father in Bucharest. After graduating from high school, he studied for a year at the polytechnic in Bucharest, after which he was expelled on account of being Jewish. In the summer of 1941, David and some other Jewish young men were recruited for forced labor on the outskirts of Bucharest. He slept at home, but had to report for work every day. After several months, his father succeeded in getting him released from forced labor in return for payment, and to buy him a ticket on the Struma, which was bound for Eretz Israel (Mandatory Palestine). Recalling the preparations for travel, David relates:

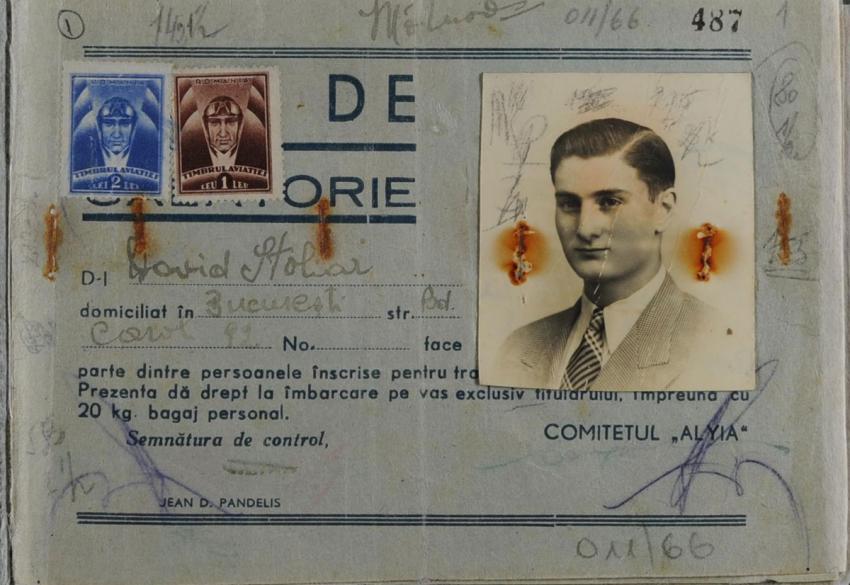

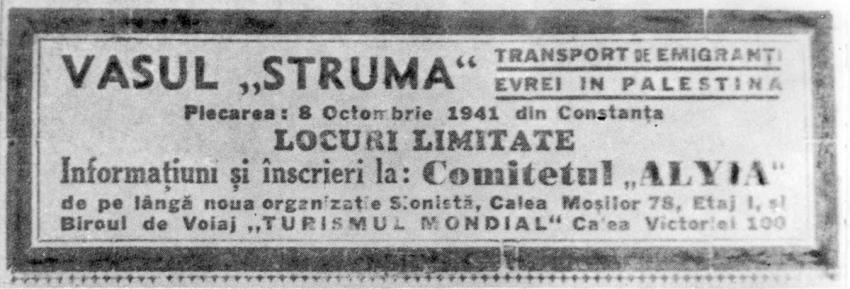

The Immigration Committee in Bucharest started registration for the journey at the price of 30,000 lei per ticket, and the price rose as demand increased…. People hastily sold all their belongings and waited with their 20 kg of luggage… They promised potential passengers immigration permits to Eretz Israel… In September [1941] the price was already 204,000 lei for an adult…. The price included a guarantee to deliver passengers to the shores of Eretz Israel, and to organize sufficient food and reasonable sleeping conditions. They were even told that the ship was equipped with a modern diesel engine… In actual fact, the Struma was an engine-less barge, and the engine installed had belonged to a ship that sank and had been lying underwater for four years, its exploded carburetor welded together….

On the day David left Bucharest, Yaakov Stoliar took his son to visit Rabbi Zvi Gutman. Rabbi Gutman had been saved twice from the pogroms in Bucharest in January 1941, and the city's Jews used to approach him for a blessing. "Rabbi Gutman cried," relates David, "He blessed me to the effect that I would reach Eretz Israel safely. I was very moved by this encounter. When I left the provisional synagogue that the Rabbi had established, I didn't say a word to my father, but we both felt that we had fulfilled a sacred duty to God… Something within me changed. Courage filled me, and my belief that I would indeed reach Eretz Israel strengthened." The Ma'apilim (illegal immigrants) made their way from Bucharest to Constanța port by train. Their identity papers and belongings were meticulously checked before they could go on board. David recalls:

Sometimes, the inspector would wickedly take something out of the backpack and turn to his friend, asking, 'Perhaps you have some newspaper to wrap up these shoes? I just got them as a present.' People didn't protest, and let themselves be humiliated… It wasn't important. At that moment, they were leaving the firetrap of Satan, whose reach had spread over all of Europe… They boarded the trains… The cries of those parting from them – Write as soon as you arrive! Take care that you don't catch cold on the ship! Be well! – were swallowed up in the rattling of the wheels. Almost 800 people were leaving the land of their birth, their homes, their childhood and adolescent dreams, to escape the chilling threat of death.

The passengers underwent further inspections at Constanța. The security police checked their names in the joint passport, and they had to hand in their Romanian documents. "Only one man, whose name had been removed by mistake from the list was turned away," relates David, "In vain he cried and begged them to let him travel, but the border personnel didn't give in – he received his life back as a gift!" The passengers' luggage was examined again by the tax officers, who confiscated many items, and by clerks from the Romanian National Bank, who appropriated money and jewelry. The passengers were undressed, and painstakingly examined. There was a ban on taking precious metals out of Romania, and they were only allowed to take their wedding rings with them. The amount of money permitted to take out of the country was also confiscated.

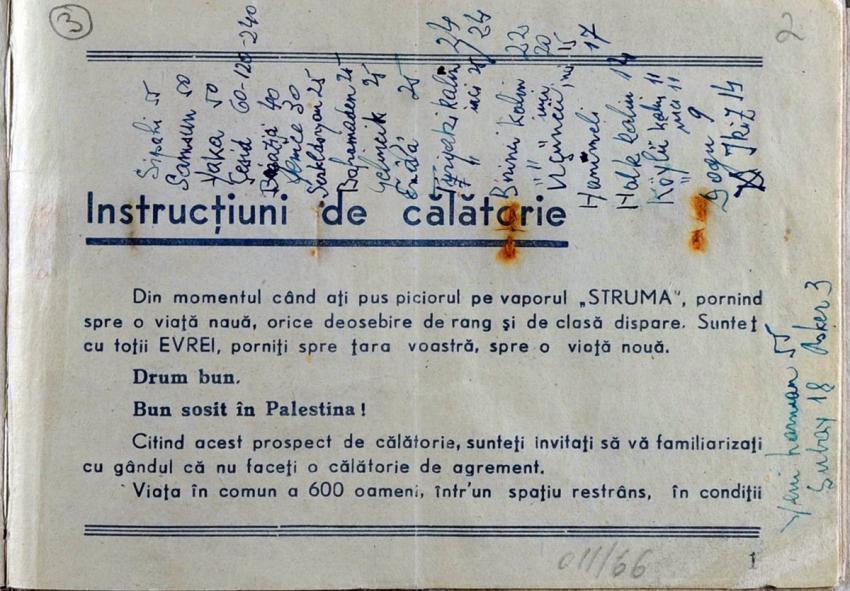

On the night of 12 December 1941, the Struma pulled out of port. Some time later the engine died, the ship became silent, and was left at the mercy of the waves. Attempts to repair the motor were unsuccessful, and after many hours, a mechanic was brought from Constanța, when distress signals were received from the crew. "After a superficial examination of the engine, the mechanic declared that he was prepared to fix it for 3 million lei", recalls David. "It was an enormous sum, and the ship's passengers didn't have any money… He only agreed to accept 250 gold wedding rings in lieu of cash after an hour of haggling." Some three hours later, the ship made its way towards Istanbul. The Turkish authorities didn't let the passengers disembark, and they were left on board in dire conditions for ten weeks. David relates:

People began to get used to the misery, dirt, overcrowding, lack of food and the cold. Bugs were removed from our shirts with a knife or razor because we no longer had any clothes to change into, nor water and soap to wash with. Baths and showers were not an option… Thanks to Dr. Löbel, a group of 30 doctors and nurses was organized that provided all the sick passengers' needs, as far as was possible in light of the lack of basic medical materials. The diabetics' plight was worse, since the Turkish authorities categorically forbade anyone to bring us insulin.

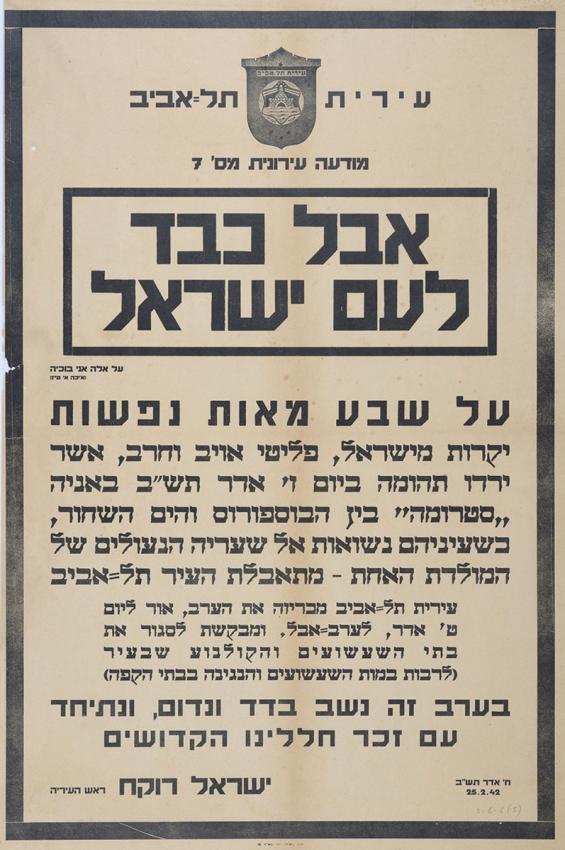

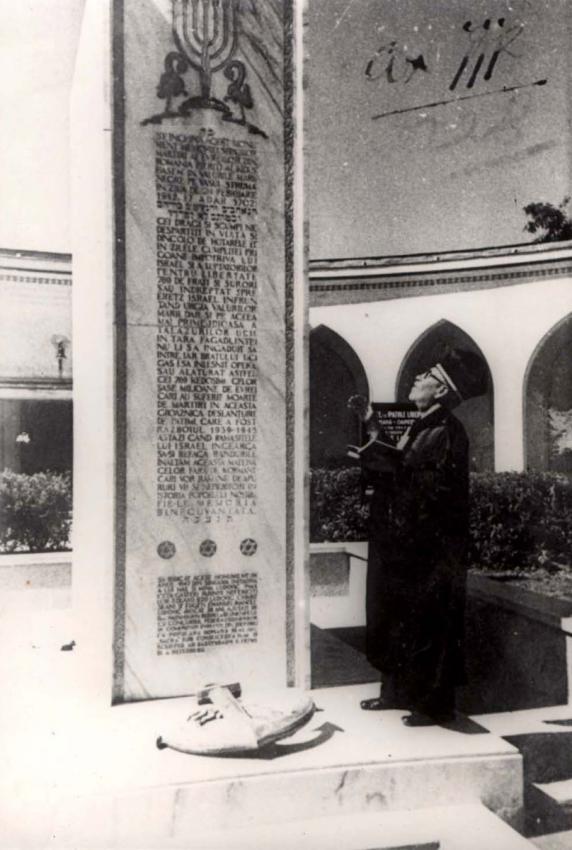

The Turks permitted nine passengers to disembark. Eight of them had entry permits to Eretz Israel, and one female passenger who started hemorrhaging severely was taken off the ship after much pleading, and brought to hospital. "It would be superfluous to describe the way people inundated them with messages and requests to pass on letters and notes written on pieces of paper to designated addresses," relates David. "They promised that they would try to approach Jewish and English organizations with descriptions of the terrible conditions on board the Struma." All pleas to let at least the children and the elderly disembark fell on deaf ears, and apart from those nine passengers, no one got off the ship. On 23 February 1942, the Struma was towed out to the open seas by the Turkish authorities. The next day, the ship was hit by a Soviet submarine and sank. David relates:

We were 8 km from the Turkish coast… Shortly before 9:00 AM we heard the thunder of bombardment and saw flames coming from the Turkish coast, and a second later, everyone on deck saw a torpedo speeding towards us. A deafening explosion ripped through the ship… I only remember that a superhuman force lifted me into the air; after a few moments I fell back down and landed in the water. From the moment of impact, no more than a minute passed before the vessel disappeared without a trace. It was literally swallowed up by the waves in the blink of an eye… Just a few planks of wood floating on the surface remained of the Struma… There were a few dozen people in the water, men and women who tried to save themselves, but the screams and cries for help dissipated and vanished amidst the vast expanse of the sea… The waves were cold as ice, and my limbs lost all feeling... I managed to lay my hands on a large piece of driftwood and to climb up onto it… Not even four hours had passed before I comprehended that I was the only one who remained.

David spied one of the Struma's floats some 40m away from him, and used the last vestiges of his strength to reach it. Night fell, and David found the ship's second officer, Lazar, near him in the water, and lifted him up onto the float. During the night, Lazar froze to death and sank into the depths. David was left alone, desperate, and tried to take his own life. After some 24 hours in the freezing water, David was spotted by a Turkish boat and taken to a small fishing village, where he was wrapped in blankets. Following two days in which he teetered between life and death, David was interrogated by Turkish policemen. He fainted in the course of the interrogation, and was taken to hospital by ambulance. He relates:

I was in hospital for 14 days. On the first day, I was visited by Mr. Simon Brod, President of the Istanbul Jewish community, who had received special permission to come and see me. He visited me every day, sometimes twice a day… Two days later he came with a Jewish doctor, who immediately gave the order to bandage my fingers and toes with camphor dressings and to change them several times a day. Thanks to the prompt and dedicated treatment I received, my fingers and toes were spared gangrene and amputation.

Once he was back on his feet, David was taken to the Turkish security police. He was incarcerated in a small cell, where he was held as a political prisoner for 48 days and interrogated daily. He was released on 23 April 1942. He relates:

That day, Mr. Brod informed me that all my papers were ready, including the British permit. In other words, of 770 permits that would have had to be issued were it not for the disaster, one permit was issued. After Mr. Brod ensured that I had everything I needed, I departed the next day under Turkish guard, for the Syrian border. I left Turkey, and set out for Eretz Israel.

On 14 September 1942, David's mother Bella Leichiman was deported from France to Auschwitz, where she was murdered. In 1978, Bella's brother, Binyamin Leichiman, submitted a Page of Testimony to Yad Vashem in her memory.

Approximately one year after he reached Eretz Israel, David enlisted in the British Army.

David Stoliar's full-length testimony is preserved in the Yad Vashem Archives.