Weddings after Liberation

After the war, there were many young Holocaust survivors, most in their 20s and 30s, the sole survivors of large families. These young men and women sought to get married quickly and to start families, in order to alleviate their loneliness, establish a place of their own in the world after years of wandering, and to rebuild the chain of familial and Jewish continuity. Liberation was perceived as meaningless unless accompanied by a return to normal life, as far as was possible. The paradigm of this return to normality was the establishment of a new family. Thus, one of the first tasks that occupied many survivors after liberation was the quest for a spouse.

Some couples met in the DP camps. Some survivors preferred to marry people they had known before the war and with whom they shared common memories, or to marry relatives. The weddings were joyful, but overshadowed by sadness due to the absence of those who had been murdered, and the weight of the couple's Holocaust experiences. On some occasions, several couples got married at the same time.

The will to live transcended all else. In the initial years after liberation, many of the She'erit Hapleita (surviving remnant) got married. By the end of 1946, approximately 1,000 babies were born in the British Occupied Zone of Germany, 200 of them at Bergen-Belsen.

Noach and Kala Selzer

Kala Londner was born in Dombrowa, Poland. During the war, she was confined in the city's ghetto with her family, and from there, she was deported to the Grünberg labor camp, a subcamp of Gross-Rosen, where she worked in a textile factory. In late 1944, she was forced on a death march. On one of the stops along the way, she escaped to the fields with her friends, and thus survived the war.

Noach Selzer was born in Kowel, Ukraine. During the war he was an officer in the Red Army, where he served as a dentist. He attained the rank of Captain, and was decorated for his achievements. He moved to Poland in 1946, and reached a displaced persons camp in Austria.

Kala and Noach got to know each other at the Bindermichl refugee camp in Linz, as they made their way westward with the "Bricha" movement. Together they moved to the Ranshofen camp near Braunau, and worked at various UNRRA dental clinics in refugee camps in Austria, Noach as a dentist and Kala as his assistant.

Noach and Kala got married on 19 September 1946, three months after first meeting, at a modest ceremony attended by a few friends. Both their families had been murdered in the Holocaust. Kala's wedding dress was sewn from a piece of brown chiffon that she bought in Poland after liberation, and she used a white napkin as a veil. On the same occasion, their good friends Yitzhak Brill and Erszy (Elizabeth) Weill got married. Noach and Itzik made the wedding rings in a dental clinic laboratory, fashioning them from a five-ruble gold coin. After the wedding, Noach and Kala lived in an apartment with two other couples.

The Selzers immigrated to Israel in 1948 on the ship, "Galila". They lived in the Beit Lid Ma'abara (temporary camp for immigrants), and then moved to Jerusalem. They have three children.

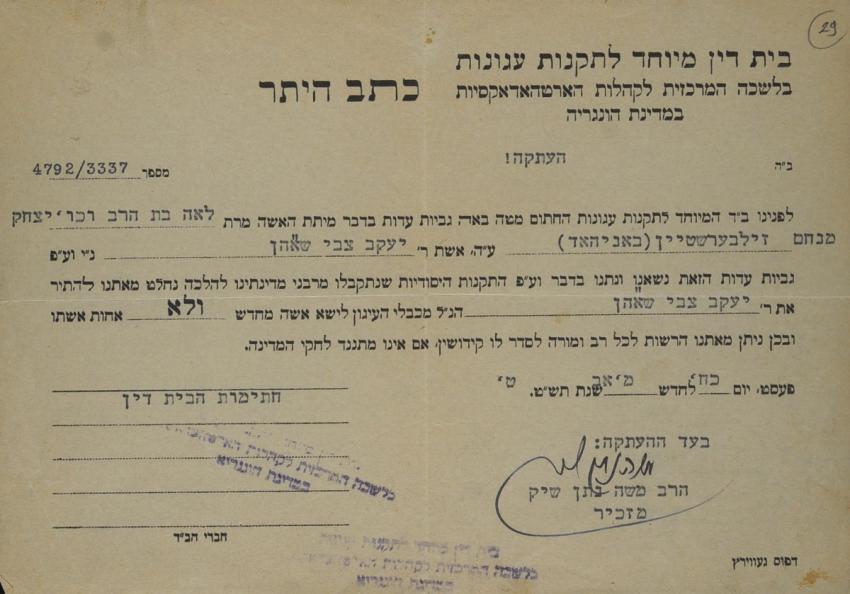

Agunot after the Holocaust

According to Halacha, Jewish law, a Jewish woman whose husband has vanished without a trace is considered a married woman, and until there is conclusive proof of her husband's demise, she cannot remarry. The official term for this legal status is Aguna (lit. chained). A man in the same situation is also forbidden from remarrying until the fate of his wife has been confirmed.

After World War II, many Holocaust survivors sought to rebuild their lives and raise families. A large number of them, who had married before the war or in the course of the war years, did not know what had become of their spouses. As such, the subject of Aginut (the situation of being "chained" in a marriage) was significant, even existential. Rabbis of the period supported the survivors, encouraged their desire to start families, and attempted to solve this complex, thorny problem. These rabbis searched for witnesses who would be able to testify as to the death of the spouse in question. In many places rabbinical courts were established, which sought information. They researched the methods of mass-murder implemented by the Germans, in order to establish the chances of surviving the various massacres. They heard survivor testimonies, so as to understand the fate of the missing spouse, and did their best to release the man or woman from their Aginut. They used creative halachic (pertaining to Jewish law) solutions and extenuating circumstances, and were prepared to accept less-than-solid evidence in order to enable these survivors to remarry. Initially, testimonies were gathered and signed by the witnesses, and later on the rabbis issued a marriage permit and signed it. The information gathered and the rabbinical rulings were documented in the community ledgers. These rabbinical courts were confronted with many obstacles, including the volume of cases and the absence of documentation and witnesses deriving from the totality of the destruction wreaked in the Holocaust.

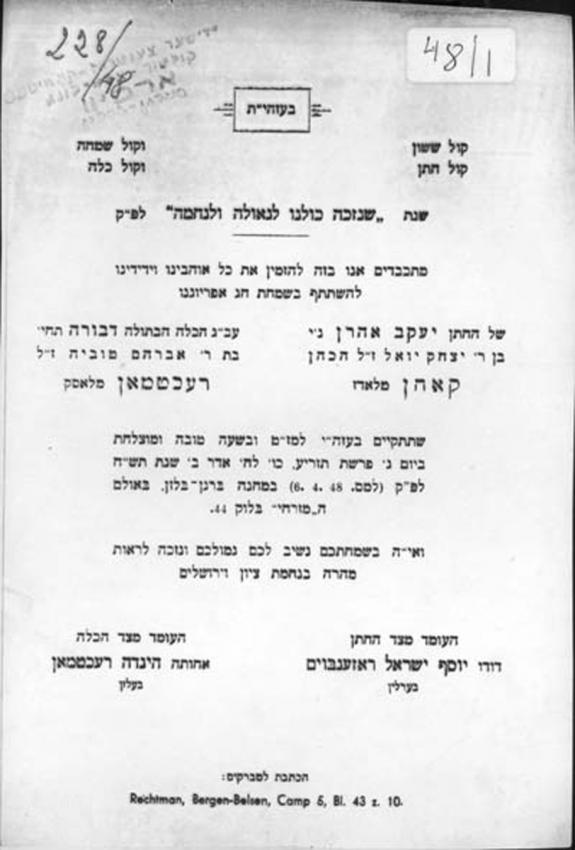

Weddings in the Absence of Family Members

While weddings after World War II were joyful occasions, celebrating the establishment of new Jewish homes and the renewal of family lineage after the devastation and loss suffered in the Holocaust, they were also overshadowed by the lack of participating family members.

The survivors' descriptions of their weddings, and the invitations themselves reveal the sad, painful aspects of postwar weddings. In the absence of a father or mother to invite the guests to their children's wedding the bride and groom often issued the invitations themselves, and sometimes they were issued by an uncle or cousin. Friends and relatives who survived tried to fill the place of the absent parents, and accompanied the bride and groom to the Chuppah (wedding canopy).

The ceremonies were emotional, and served as a moment to think about the family members who were no longer alive. Under the Chuppah, mention was made of the souls of the bride and groom's parents, and sometimes, the "El Maleh Rahamim" prayer was recited. The rabbi and wedding guests tried to alleviate the sadness and yearning by dancing, giving speeches, and providing the new couple with a special room and any other personal requirements.

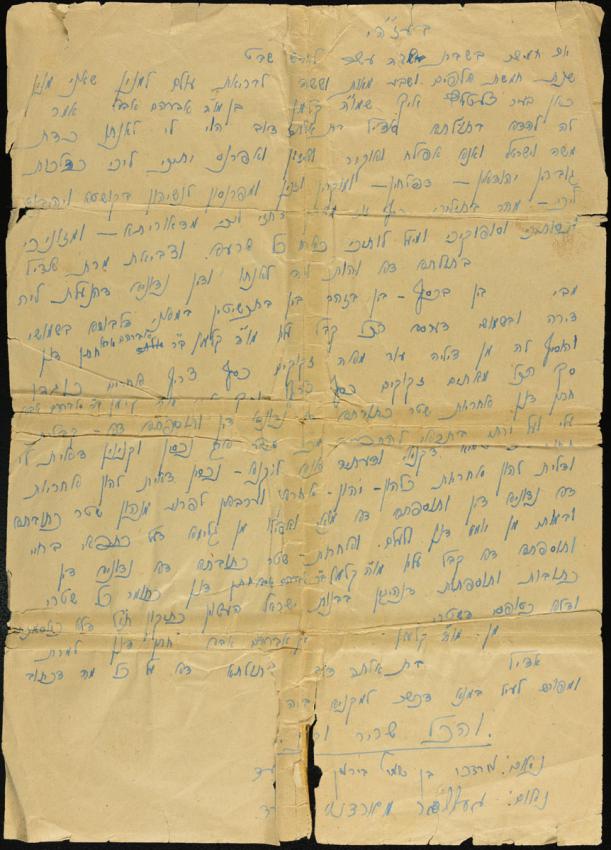

Holocaust survivor Esther Eisen, who got married after the war, describes her wedding that was tinged with the sadness of absent relatives:

"As I stood there, I could visualize my mother and father participating in the wedding, and very close to them stood my brother, who was never afraid of saying what he thought…. I had something to say to him, also to Father and especially to Mother, to make them happy: "Look, with this ring I am marrying the most wonderful boy… And as you can see, I love him very much."

Lilly and Ludwig Friedman

Lilly Lax was born in 1924 in Czechoslovakia. In the course of the war, she was deported to Auschwitz and transferred from there to other camps. She was liberated at Bergen-Belsen in April 1945 with two of her sisters. They were sent to a hospital in the nearby city of Celle to recuperate, and planned to remain there until immigrating to the US. In June 1945, while waiting with her sisters for food rations in the DP camp next to Bergen-Belsen, Lilly met Ludwig (Aharon) Friedman.

Born in Czechoslovakia, Ludwig was also deported to Auschwitz and liberated at Bergen-Belsen. After the war, he lived in the adjacent DP camp. During his time there, he would go to neighboring farms and milk the cows, in order to distribute milk to the Holocaust survivors at the camp. Arrested by the British for stealing milk, he was put to work in the DP camp kitchen. Ludwig and Lilly got engaged in the fall of 1945, and they got married on 27 January 1946.

In order that Lilly could be married in the white dress of her dreams, Ludwig acquired a parachute from a German former pilot, who bartered his old piece of white cloth for a kilogram of coffee and some packets of cigarettes. Lilly hired the services of a seamstress, who sewed a bridal gown from the parachute. The wedding took place in the Celle synagogue, and as a wedding gift, Lilly sewed Ludwig a purple velvet Tallit (prayer shawl) bag. Later on, Lilly's sister Feige, her cousin Rosie and other Holocaust survivors wore Lilly's bridal gown at their weddings.

In 1948, Lilly, Ludwig and their 10-month-old daughter immigrated to the US, where they joined Lilly's sisters.

Ada and Kalman Blacharz

Ada and Kalman Blacharz from Bedzin were close friends who were both active in the Gordonia Zionist youth movement. Bedzin was occupied by Nazi Germany in September 1939. When the ghetto was established in April 1943, Ada and Kalman were incarcerated there with their families, and worked together at "Farma", an agricultural collective set up between Bedzin and the Sosnowiec ghetto.

The couple's first wedding was held in May 1943 in the Bedzin municipality. They arrived there accompanied by a Jewish policeman, and were married in a civil ceremony. Kalman had Paraguayan citizenship that he had obtained with Nathan Schwalb's help, and the couple hoped that their married status would enable Ada to obtain the same citizenship and that they could emigrate from Poland. This hope turned out to be illusory.

In August 1943, Ada and Kalman were deported to Auschwitz together with their fellow Gordonia members. On the journey to the camp, Kalman wanted to jump from the window of the cattle-car, but Ada refused, fearing that they would be shot by the Germans. Not wishing to part from her, Kalman remained together with Ada in the cattle-car. On their arrival at Auschwitz, men and women were separated. Kalman managed to shout to Ada in Polish: "We will overcome this period and we will be reunited at home after the war."

Ada recalled that Kalman's parting words helped her to hold on during the hard times. Six months later, Ada and Kalman met at the camp. From that time on, Kalman would send Ada food parcels with the help of a fellow prisoner, until he was transferred to another camp.

After liberation, Ada and Kalman searched for each other. They were reunited six months later and got married again in Zettlitz, Germany. A US Army Chaplain officiated at the wedding, writing the Ketubah (marriage contract) from memory. The rabbi gave Ada and Kalman a handkerchief as a wedding present. The couple immigrated to Israel, and had two daughters.

Kalman died in the course of his military service in the Six Day War.