Liquidation of the Jewish Community in Monastir

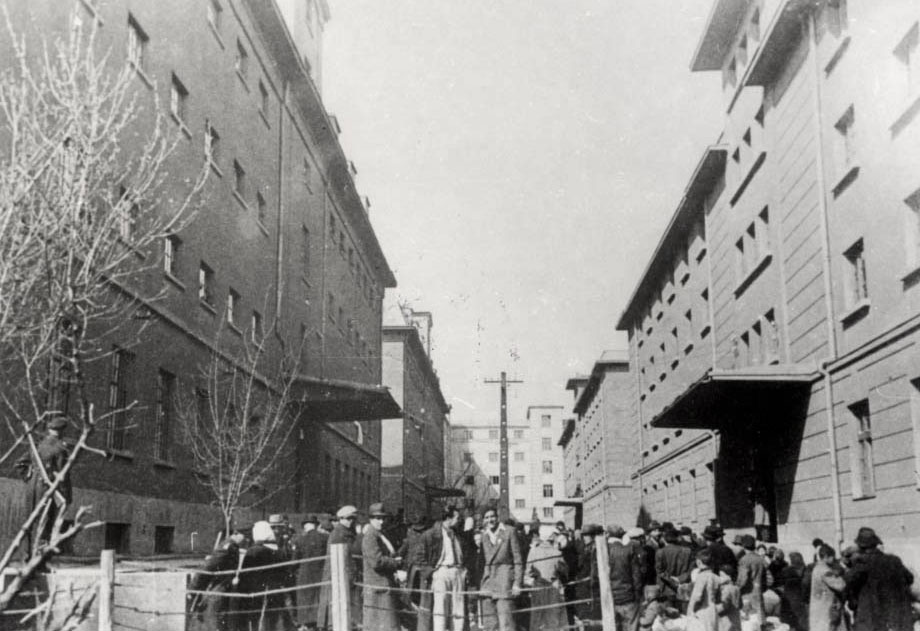

Jews on stools in the “Monopol” tobacco factory storerooms, Skopje, March 1943

Meticulous Planning

By the end of 1941, negotiations between Nazi-German representatives and the Bulgarian government had already begun on the deportation of Jews from the Bulgarian territories. For the next year, antisemitic propaganda, pamphlets and books were distributed throughout Bulgaria. In August 1942, the Commissariat for Jewish Affairs, that supervised all Jewish property and signage was established, and in September Jews were forced to wear the yellow badge. All the while, negotiations between the Bulgarians and the Germans regarding the fate of the Jewish population of Bulgaria were continuing, and in October 1942 discussions regarding their deportation were concluded. On 22 February 1943, Alexander Belev and Theodor Dannecker - Adolf Eichmann’s representative in Bulgaria – signed an agreement on the initial deportation of 20,000 Jews to “Eastern German Regions” (Poland). The agreement detailed the outbound stations, the number of people, the number of trains and the order in which they were to be loaded. At the first stage, the agreement related to 12,000 Jews from Thrace and Macedonia. This was the only agreement signed between Nazi Germany and another country concerning the deportation of its Jewish population.

After one week, on 2 March, the Bulgarian government approved the agreement. On the same day, the government also decided that the deportees would lose their Bulgarian citizenship (those Jews in the annexed Bulgarian territories were never citizens – this decision was regarding Bulgarian Jewry to be deported in the first stage); in addition, all property belonging to those deported out of Bulgaria, as well as that of the community, was confiscated.

Immediately following the signing of the agreement, preparations for the deportation began. Heading the operation throughout Macedonia was Zahari Velkov, with Kiril Stoimenov in charge of the region that included Monastir.

The Aktion

At dawn of 11 March 1943, Commissariat representatives, headed by Stoimenov, broke into Jewish homes and hauled out their inhabitants. Earlier on, at 2 am, hundreds of “trustworthy” people had gathered at police headquarters across Macedonia. Their job was to evacuate and deport the Jews. In addition, hundreds of wagons were assembled outside the police buildings, their drivers recruited to transport the luggage belonging to the deportees and the infirm.

The Jewish quarter of Monastir was divided into ten parts, with each assigned a unit of policemen and soldiers. A curfew was imposed on the city, and all movement forbidden. Between 5 and 6 am, the Jews were told that they had one hour to be ready with their luggage to travel to the center of the country. At 7 am, they were taken out of their apartments and assembled. After the apartments were evacuated, a policeman checked them to ensure that all the family members had left. The Jews were marched from the assembly points and frisked – all valuables were confiscated. 793 Jewish families, 3,351 people, were deported from Monastir on the cold and snowy morning of 11 March 1943.

“They loaded us and our luggage onto wagons, 60 people in each, many of them standing. There was no water. The children were crying…a woman crouched down to give birth… at midnight we arrived at Skopje. The wagons were opened and we were pushed into two large buildings… inside the Bulgarian soldiers beat us relentlessly. We were pressed into the building. With daylight, we realized we were in Skopje, in the government tobacco company building, and that all the Jews of Macedonia had been concentrated there that day.”

Albert Sarfati, survivor from Monastir

At the “Monopol” Camp

Zachary Velkov, who headed the operation to gather and deport the Jews of Macedonia, had searched for a suitable place to use as a detention camp before their deportation. At first, two camps were pinpointed, one in Monastir and the other in Skopje, but due to German pressure on the Bulgarians to bring forward the deportation of the Jews of Bitola, the two-camp plan was cancelled; one camp would now have to suffice. The warehouses of the “Monopol” government tobacco company in Skopje were chosen as the most suitable venue, and the buildings were duly prepared.

According to camp rules, the detainees were forbidden to speak with or meet anyone outside the camp. Doctors from outside were forbidden to enter. The sick were aided by Jewish doctors, who were also being detained at “Monopol.” During their temporary stay at the camp, many prohibitions were announced, including smoking, playing games, reading newspapers, drinking alcohol, receiving food from outside the camp – even looking through the windows, writing to one another and moving from room to room. The prisoners were allowed to use the bathrooms only in groups and under guard. Just 15 bathrooms were provided for the 7,300 prisoners. Disease was widespread, and not one day passed without somebody dying.

“The stench quickly became unbearable… when people peeked out of the windows the policeman shot them… hunger was rampant. Only on the fifth day was a cook appointed, but there were not enough pots… food was distributed once a day… one of the police officers hit us more than his colleagues… a sadist like no other. Throughout the day he would walk about with an enormous whip and beat people at random… a general directive was given to provide milk for the babies, but the policemen and agents drank it…”

Helena Leon Ishach, a doctor from Monastir

On 11 March, eleven leaders of the Jewish community of Monastir (among them Leon Kamhi) that had been deported to the Bulgarian countryside in December 1942 were brought by train from Sofia to Skopje. On arrival, the policemen beat them and brought them to the local prison. The following day they were brought by guards armed with bayonets to the “Monopol” factory warehouses where, as stated, all the Jews of Macedonia had been assembled.

The Deportation to Treblinka

All the Jews imprisoned at “Monopol” were deported to the Treblinka death camp, where they were murdered. They were brought in three transports, although the original plan was for five.

On 21 March, elite Bulgarian and German officers arrived in Skopje, among them the German Ambassador in Sofia, Adolf Heinz Beckerle, as well as Alexander Belev and Theodor Dannecker. It was the eve of the first transport of the Jews of Macedonia, and they seemingly wished personally to supervise the operation they had organized. They passed through the rooms looking at the prisoners, who were standing silent and afraid. 7,144 Jews were sent from “Monopol” to Treblinka; 12 died along the way.

The first transport, on 22 March 1943 – some ten days after they had been brought to “Monopol” – took 2,388 Jews to Treblinka. Just the day before, the number had been fixed at 1,600. These captives were given some food, but just before they left, a surprise announcement was made that a further 800 people would be joining them. As the train was about to leave, the extra people were pushed into the wagons without managing to take their rations. The train had 40 wagons, each with a small pitcher of water and some buckets for toilet purposes. The number of people in each wagon reached 80. One captain and 120 soldiers – all Bulgarian – appointed by the Bulgarian Interior Ministry, supervised the first transport. They accompanied the train until Lapovo, where they were met by German policemen. German security police head Rot took charge of accompanying the transport to Treblinka. Six days later, in the morning hours of 28 March, the transport arrived. Four people had died during the journey.

Three days after the first transport departed, on 25 March, the second transport left carrying 2,402 people. A German police unit headed by Sgt. Buchner had come to Skopje some two days earlier to organize and accompany the transport. One of the wagons had no windows at all. When the Germans were approached to exchange the wagon for another, the coarse response was that there was no time to find another wagon; the transport had to leave immediately. It arrived at the Malkinia train station on the afternoon of 31 March. Within one hour, 20 wagons had been brought to Treblinka. The rest of the wagons remained at Malkinia until the morning of 1 April, when they were taken to the camp. Three people had died on the way to the death camp.

The third transport, with the final 2,404 Jews detained at “Monopol,” left in the afternoon of 29 March, on a similar route to the ones preceding it. The journey ended on 5 April at 7 am. Between 9 and 11 am, the passengers were taken off the wagons at Treblinka. This transport was also organized and accompanied by groups of German policemen. Five people died along the way.

Eight Survivors

The “Monopol” concentration camp ceased operating on 29 March 1943, the day the last transport of Jews from Macedonia left for Treblinka. It had been used for 18 days, during which time 165 Jews had been released in line with orders from the Bulgarian authorities: 32 doctors and their families, 35 pharmacists and their families, 74 Spanish citizens and first-degree relatives, 19 Albanian citizens and first-degree relatives, and 5 Italian citizens and first-degree relatives. Among those released were just three members of the Monastir community: the doctor Helena Leon Ishach, her husband and her mother. In addition, five members of the Monastir community managed to escape from the camp: Niko Pardo, Allegra Aroesti-Pardo, Albert Moshon, Albert Sarfati and Joseph Kamhi.

Over ten days, Niko Pardo tried to escape three times: the first from the train bringing the Jews of Monastir to Skopje; the second in an ambulance leaving the “Monopol” camp – but he was caught, beaten and returned to the camp; and the third time two days before the final transport, when he managed to steal away with the group of Jews taken for forced labor. This time he found himself outside of “Monopol.” Following Niko was Allegra, the wife of his brother Aharon, who had emigrated to Eretz Israel in 1941. Allegra escaped through a hole in the wooden fence surrounding the camp. Niko and Allegra stayed with relatives in Skopje with Spanish passports – those Jews that had been released from the camp. The next day they left on a tortuous journey that took them to the Albanian border, where they were imprisoned by the Albanians for three months, and then released. They stayed there until the end of the war.

Albert Moshon Aroesti, 36 years old, left on the night of 24/25 March, hid for 24 hours with the Apostole Shumanov in Skopje, and then moved to Uroshevats in the Italian-occupied region, where he stayed until the end of the war.

Albert Sarfati escaped from the camp on 26 March and survived.

Joseph Kamhi, one of the 11 leaders of the Monastir Jewish community that had been exiled to Sofia and then taken to “Monopol,” found shelter for a night with the Italian Consul Larosa in Skopje. The Consul suggested that Kamhi dress up as an Italian soldier and flee the city. But Kamhi managed to reach the Albanian border on his own devices, and he survived.

* * *

An edict from the Council of Bulgarian Ministers ordered the liquidation of the property left behind by the Jews. Cash and valuables were given to the Bulgarian national bank, and moveable assets were gathered in special warehouses. The Jewish property was sold for pennies, and the money collected was handed over to the Commissariat for Jewish Affairs. The liquidation of Jewish property in Monastir began on 24 March 1943, just two days after the first transport left Monopol for Treblinka.

The fate of Bulgarian Jewry was better. Their intended deportation was avoided due to the involvement of certain circles in the Bulgarian establishment, including clergy, politicians and members of the Bulgarian royal family.