"We saw the same thing every day: dead bodies, killings and beatings."

Tema Weinstock

Introduction

On 20 January 1945, approximately 1000 female Jewish prisoners were evacuated from the Schlesiersee (today Sława) camp in Upper Silesia, western Poland, a region annexed to Germany. These women were forced on a death march in a southwesterly direction. On the way, the prisoners passed through other camps, and more women were added to the march.

On 5 May 1945, after covering a distance of over 800 km, the march ended in the town of Volary (German: Wallern) in Czechoslovakia, not far from the border with Germany and Austria.

106 days of rigorous marching through snow. 106 days of gnawing hunger and sickness, humiliation and murder.

Of the approximately 1,300 women who marched to Volary, some 350 survived.

The exhibition is based on the most updated research on the death marches, testimonies of survivors and US Army veterans, and documentation from the trial of death march commander Alois Dörr.

The Days Before the Death March

Forced Labor by Jewish Women in Schlesiersee: Digging Anti-Tank Trenches

In October 1944, approximately 1,000 female prisoners of Auschwitz-Birkenau - young women who had come mostly from Hungary and from the Lodz ghetto - were sent by train to Schlesiersee, a sub-camp of Gross-Rosen in Lower Silesia, western Poland, a region that had been annexed by Germany.

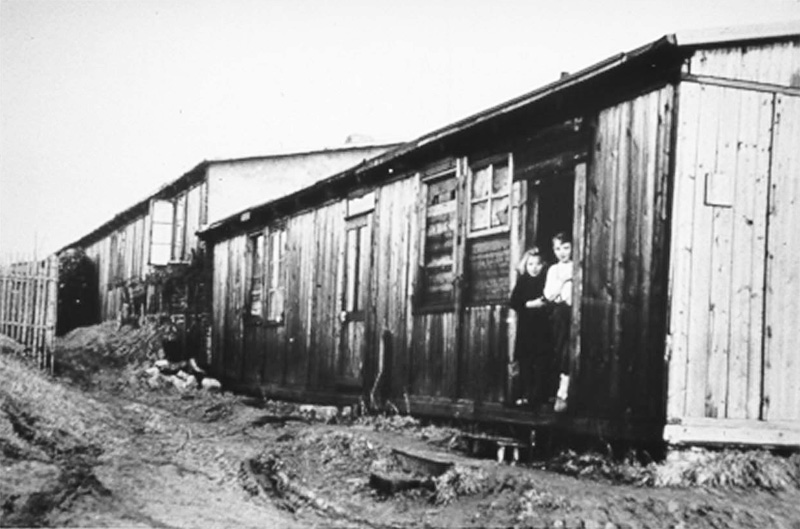

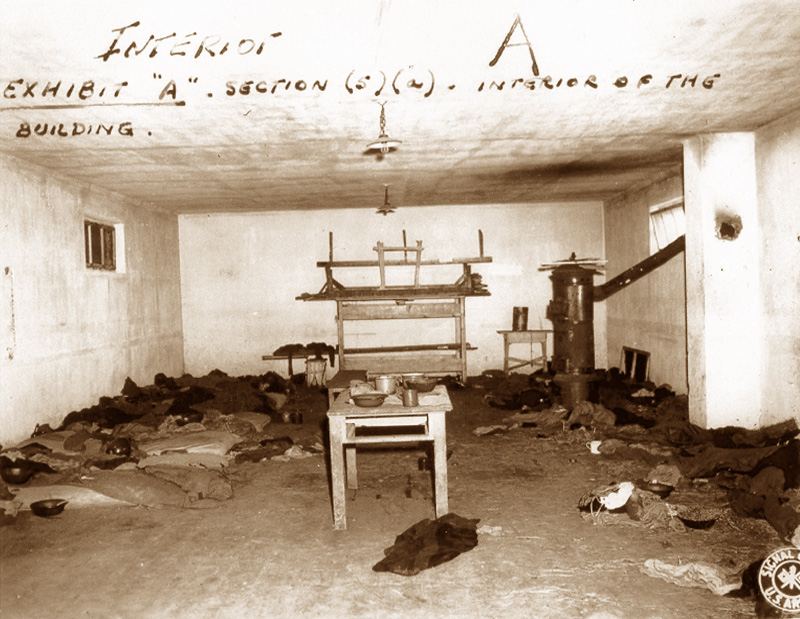

They were housed in two adjacent farms, where they lived in appallingly unsanitary conditions and slept on straw that had been strewn on the floor.

The commander of the camp was Karl Herman Jäschke of the German Security Police (Schutzpolizei), formerly a policeman in the Breslau prison.

Each day, the women marched about 3 km from the farms to the forced labor site, and back. They were forced to dig anti-tank trenches in the snow-covered earth, using only shovels and other manual work tools. It was bitterly cold, and they were clothed in thin garments and given very little food. Lice spread from one to the other, and many of the women fell ill. Dozens perished in the course of the three-month forced labor period. The dead were buried next to the fence surrounding their living quarters.

It was bitterly cold in Schlesiersee, and since we were very poorly dressed some of us women took the one blanket they possessed and wore it out to work. A check was made three or four times of all the woman returning from work, and all those found wearing their blankets were given as punishment 25 whip strokes…The girls were whipped until they were bloody. Of the hundred girls I worked with, thirty received this punishment at one time. We used to be beaten also for having our clothes a little wet or dirty. It was practically impossible to avoid this since our work consisted of digging anti-tank ditches in the snow. Testimony of Zisla Heidt, given to a US intelligence officer on 16 May 1945 in Volary.

With the approach of the Red Army, the Germans evacuated the women from Schlesiersee. This evacuation turned into a death march.

The Sixth Day of the Death March, 40 km From the Start of the March

Thursday, 25 January 1945

Mass Murder in Alt-Hauland

The death march of the female prisoners of the Schlesiersee camp under the supervision of camp commander Jäschke, began on 20 January 1945. Jäschke was given orders to leave no one behind. The women were marched on foot for eight days, covering a distance of some 95 km in a northwesterly direction, until they reached the Grünberg camp. On leaving Schlesiersee, each woman was given one loaf of bread. They did not know if and when they would be receiving more food. Clad in thin garments and wearing unwieldy wooden clogs, they marched in the freezing cold. The weaker ones were pushed in wheelbarrows by their friends. The guards urged them on, so they wouldn't slow down. Anyone who couldn't keep up was shot. It is unclear how many women survived the journey and reached Grünberg. At least 150 were shot, or perished from hunger and exhaustion on the way.

On 25 January, after having marched more than 40 km, some 40 women, the weaker prisoners, were murdered in the vicinity of the village of Alt-Hauland, today Stary Jaromierz. Their bodies were later moved to a mass grave in the cemetery in nearby Kargowa.

A committee established to research crimes committed against the Polish people in Zielona Góra (formerly Grünberg) investigated the murder of the women in the forest, gathered testimony from the locals, and summarized as follows in their report of 1967:

The German guards put aside 38 exhausted women who could not continue marching, and from then on, they no longer received anything to eat. Afterwards, at around 15:00, they were loaded onto three wagons… and removed together with seven guards who accompanied the transport to the forest. On arrival in the forest, the guards ordered the wagon drivers… to halt. They then began to murder those defenseless women. They were murdered in cold blood, in the most inhumane manner possible.

One of the wagon-drivers said in his testimony:

The women… looked miserable and exhausted…the head of the village said that they were being taken to the hospital… When we reached the forest, they [the German guards] ordered us to stop, and started shooting the women. They pulled them by the hair and shot them… After the women were buried… those guards were drunk, and they continued to drink. They also offered me alcohol.

The Ninth Day of the Death March, 95 km From the Start of the March

Grünberg Camp

On 28 January 1945, the women from Schlesiersee arrived at Grünberg. Hanah Kotlicki (née Anny Keller), a prisoner in Grünberg, recalls their arrival:

Two days before we left Grünberg, a group of some 1,000 women arrived at our camp… most of them from Hungary and woman from Lodz… we didn't know that such things existed. Girls… without hair, wearing wooden shoes without socks, wrapped in rags. Each one with her grey blanket. They arrived after a grueling march. It was winter and they had been sleeping outdoors… the first thing they did when they arrived was to break into our cupboards and steal everything we had… they were very hungry. They hadn't eaten or drunk in a few days. We looked at them and we couldn't believe that human beings could look like that… little did we know that the same fate would befall us.

In February 1942, a forced labor camp for Jewish women was established in Grünberg, northwest of Breslau. The women were made to work in the local textile factory DWM (Deutche Wollwaren Manufaktur). Most of them were young – between the ages of 15 and 30, and had come to the camp from East Upper Silesia in Poland. They worked 12-14 hour shifts. On 1 July 1944, the camp went from being a forced labor camp established by Organization Schmelt (an economic network that managed a chain of sweatshops and camps exploiting the Jewish workforce in East Upper Silesia, Lower Silesia and the Sudetenland) to a sub-camp of Gross-Rosen, and the conditions deteriorated. At the end of November 1944, there were 971 female prisoners incarcerated in Grünberg.

One or two days after the women from Schlesiersee arrived, Grünberg was evacuated. The prisoners of Grünberg and Schlesiersee were divided into two groups.

The first group, numbering some 700 women, was marched in a northwesterly direction until Jüterbog, and was then loaded onto a train. In the course of a month, these women covered over 400 km. Many perished or were murdered along the way. The exact number of victims is unknown. The survivors of this march reached Bergen-Belsen.

The second group, some 1,100 women, was marched approximately 480 km in a southwesterly direction, and reached the Helmbrechts camp in Bavaria five weeks later.

-

Holocaust survivor Lilli Silbiger recalls the treatment of prisoners at the Grünberg camp

-

Holocaust survivor Gerda Klein talks about the work at the weaving machine in the Grünberg camp

-

Holocaust survivor Pauline Kleinberg recalls the humiliating selection at the Grünberg camp

-

Holocaust survivor Sara Lebron talks about friendship and mutual support at the Grünberg camp

The Tenth Day of the Death March, 120 km From the Start of the March

Monday, 29 January 1945

Day 10 of the March: the Start of the March to Helmbrechts – a Stop at the Christianstadt Camp

On 29 January 1945, the prisoners from Grünberg set out, some without shoes, their feet wrapped in rags. Their possessions consisted of a thin blanket, a tin bowl and a spoon. Each received a hunk of bread. The commander of the march was the same man who had brought the prisoners from Schlesiersee – Karl Herman Jäschke.

The women who had come from Schlesiersee were in the worst shape. Staying at Grünberg for only a day or two, they had not yet recovered from their previous march. After some 6 km, one of the women, Amalia Klagsbald, collapsed. Her friends tried to help her, but one of the guards shot her in the head. Her body was left where it lay.

On 31 January they reached Christianstadt, a labor camp for women situated some 40 km southwest of Grünberg, with a munitions factory. At Christianstadt, a few dozen women escaped the ranks of the marchers. Some returned to Grünberg, while others were caught and returned to Christianstadt. In her testimony, Cila Federman (née Magrkevits) recalls:

We reached Christianstadt…all the streets there were full of people who had fled from the Russians. I started to walk with all the Germans… suddenly I met my friend Mania… she had also escaped… and Mania was with a girl from Leipzig who could speak German, Hanka (Anny Keller). Hanka said that we should say we are refugees who need a place to sleep for the night… we went into a house and they gave us a bed… We fell asleep… in the middle of the night, we heard knocking at the door… Police!…They took us to the police station, where there were already some sick girls whom they had put on a sled… we had to drag them a few kilometers until we reached the camp where the girls were… we got a terrible beating… the man who had brought us told the camp guard to watch over us until morning… he would hang us with his own two hands, he said… our friend Hanka spoke to the German and convinced her to let us out of the cellar where we had been locked up.

The Sixteenth Day of the Death March, 185 km From the Start of the March

Sunday, 4 February 1945

Day 16 of the March: Murder of Escapees near Weisswasser

On 2 February 1945, the march of the prisoners continued, following a stay of some two days in the Christianstadt camp. It would seem that some female prisoners from Christianstadt were added to the group of women that had arrived from Grünberg. They continued in a southwesterly direction. Some women who had come from Grünberg took advantage of the chaos that ensued when the camp was evacuated and escaped.

Every escape attempt foiled by the march escorts resulted in savage fatal beatings or in the shooting of the escapees. In the course of the journey from Christianstadt to Weisswasser, which they reached on around 7 February, there were several escape attempts. Some of the escapees were caught. Of those who were caught, several were beaten and shot; this was the first time that Grünberg prisoners witnessed a public execution, a sight which left an indelible scar.

Gerda Weissmann Klein, a survivor of the march, describes the will to escape in her memoir All But My Life:

We began toying with the idea of escape. Several girls had already slipped away under cover of darkness… "We must go," I wanted to whisper. Instead I heard my voice saying: "Maybe tonight."

"All assemble!" the voice of the SS rang out. For some moments we stood ready. Than we heard screams and frightened begging from the forest. Three SS men had rounded up fourteen girls in the forest. Now they lined them up in front of us. The commandant took out his pistol. The girls screamed. The commandant fired again and again and the girls fell, one on top of the other.

I closed my eyes and held Ilse's hand tightly. We marched on. At that moment I vowed that I would never try to escape, never take our lives into my hands, never step off the path that was leading us to death.

The 23rd Day of the Death March, 240 km From the Start of the March

Sunday, 11 February 1945

Day 23 of the March - Mass Murder in Bautzen

On around 10 February, about a week after the public execution of the escapees in Weisswasser, the women stopped for the night near Bautzen. In the morning, each woman received a loaf of bread. During the distribution, the guards discovered that some loaves were missing. No one confessed to the theft of the bread, and the missing loaves were not returned. In light of this, Jäschke, the march commander, decided to thin out the ranks. The prisoners were ordered to stand in line, and every tenth prisoner was taken to the forest and shot. Between fifty and sixty women were shot that day. Another 8 or so other women were also taken to the forest and ordered to bury the dead.

Halina Kleiner was amongst those chosen to bury the murdered women. This job earned each of the women a loaf of bread:

We ate that bread…it was "blood bread", but we ate it… There were no feelings, no emotions apart from the terrible hunger.

On 13-15 February, the prisoners reached Dresden, which was being bombed by the Allies. The massive bombardments looked like an enormous bonfire to the women, as if the whole world was going up in flames. Mary Robinson-Reichmann recalls in her testimony that some of the prisoners were forced by the guards to spend an entire night on one of the bridges, in the hope that the bridge would be targeted and that they would die. The bridge was not hit, and they survived. Over the next two weeks, the women continued to march.

On 1 March 1945, the women reached the camp of Oelsnitz. They stayed there for a day, and were divided into 2 groups. 179 prisoners who had been defined as "unfit to walk" were sent by Jäschke on farmers' wagons to the Zwodau camp. The rest of the women carried on marching.

The 46th Day of the Death March, 570 km From the Start of the March

The Helmbrechts Camp: Five Weeks in "Hell"

On 6 March 1945, 621 prisoners reached the Helmbrechts camp. Jäschke and his men left them to the mercies of the commander of Helmbrechts, SS Unterscharführer Alois Dörr and his staff. On arrival their clothes were taken away for fumigation, for fear of the spread of disease. They were forced to stand naked for hours, until their damp clothes were returned to them.

Helmbrechts was a concentration camp for women in Bavaria, some 16 km southwest of the city of Hof. The camp was established in the summer of 1944, and comprised some 600 non-Jewish forced laborers, mostly Slavs (from Poland, Russia and the Baltic states), some French women and 25 German women. They worked in the munitions factory in the town of Helmbrechts.

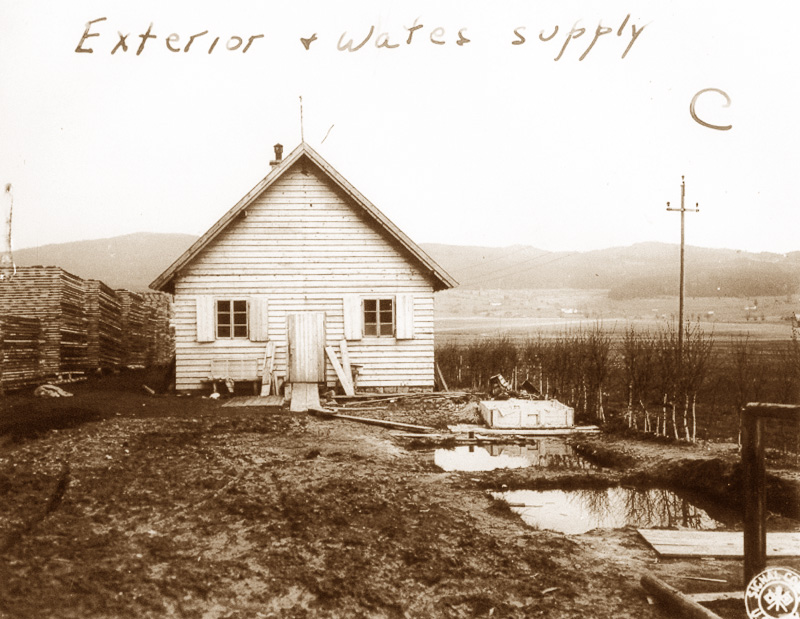

Their stay in the camp is described by the survivors as hell on earth – the hardest part of the death march. They were housed in two new huts, with neither heating or even minimal sanitation. One hut was designated for the sick, and a few dozen women were housed there on wooden bunks. In the second hut, a thin layer of straw covered the cold floor. At night, the hut doors were bolted, and the prisoners were not allowed out. The hut had two buckets for waste, which were woefully inadequate for the hundreds of prisoners, many of whom had dysentery. In the morning, they were whipped because the hut was dirty.

The prisoners received no medical treatment in Helmbrechts, and their food rations were especially meager, since they were not working.

One of the punishments meted out to the prisoners at Helmbrechts was to stand for hours under the hut roof while water dripped slowly on their heads. Frania Reifer (Frances Henenberg), a young Jewish woman from Wadowice, Poland, was punished in this manner for owning "smuggled" photographs of her murdered family. She was forced to stand barefoot for an entire day in freezing temperatures.

44 Jewish prisoners perished in Helmbrechts. These women were later buried in a mass grave in the Jewish cemetery in the nearby city of Hof.

As the western front approached, the camp was evacuated. On the afternoon of 13 April, 577 Jewish prisoners and some 590 non-Jewish prisoners including the 25 German women, left Helmbrechts together. Before they set out, Dörr ordered the distribution of spare clothing left in the camp amongst only the non-Jewish prisoners. The prisoners were escorted by the camp staff, consisting of 25 women and 22 men, including the camp commander, Dörr, who was in charge of the march.

The women marched in a southeasterly direction. 60 sick Jewish prisoners were taken in trucks to Schwarzenbach an der Saale. Many of the others became very weak, and had to be supported by their fellow marchers.

-

Holocaust survivor Eva Abrams talks about living in the sick women's block at the Helmbrechts camp

-

Holocaust survivor Frances Henenberg recalls the brutal punishments meted out to the prisoners in the Helmbrechts camp

-

Holocaust survivor Rivka Degani recalls the arrival at the Helmbrechts concentration camp

The 84th Day of the Death March, 587 km From the Start of the March

Friday, 13 April 1945

Day 84 of the Death March: 17 km, 16 Murders

Each day there were those who didn't wake up. There were the dead. At the beginning, the Germans killed many. Afterwards, we already got used to it. We saw the same thing every day. Dead bodies, killings and beatings.Tema Weinstock (née Pinczewska)

On 13 April, the women marched 17 km from Helmbrechts to Schwarzenbach. After some 5 km, one of the guards shot a prisoner who couldn't march any further, and left her body where it lay. On 16 April, a farmer found her body, her face mutilated by the bullet. She was buried in the cemetery in Ahornberg, a village occupied by the Americans a day earlier. When the march passed through Ahornberg, the starving prisoners begged for food and water, but most of the guards prevented the locals from helping them.

Some 2 km east of Ahornberg, a little before the village of Modlitz, one of the guards led two exhausted women into the forest and shot them in the head. The Americans who entered Modlitz on 15 April found their bodies and buried them where they had been found.

After leaving Modlitz, one of the guards shot two more women who could not go on. One of them did not die immediately. Locals heard her cries and groans, but no one dared approach her, and she perished during the night. On 14 April, residents of Modlitz buried her where she was found.

On the way from Modlitz to Wölbersbach, one of the guards shot a 20-year-old prisoner in the head because in her weakened state she had fallen behind the marchers. On 14 April, residents of Wölbersbach found her body and buried her there. After the march had passed through Seulbitz and reached a narrow gully, guards shot four women in the head who were too weak to go on. Their bodies were found the next day by residents of Seulbitz and buried there.

In the evening, the women reached Schwarzenbach an der Saale. The prisoners who had arrived on foot spent the night outdoors, in a fenced yard on the outskirts of the town. They were not given food or a hot drink, either in the evening or the morning. The sick prisoners who had arrived by truck were led to a building thanks to the intervention of the Deputy Mayor of Schwarzenbach. One of the female guards from the truck pushed and dragged them, and some crawled, overcome with weakness and exhaustion. The sick women did not receive food either.

During the night, five of the sick women in the building perished. Another dying prisoner was taken to the cemetery in Schwarzenbach together with the 5 dead women, and perished on the way. The six women were buried there.

The 85th Day of the Death March, 604 km From the Start of the March

Saturday, 14 April 1945

Day 85 of the Death March: US Forces Draw Near

On the morning of 14 April, the sick women were made to climb up onto a wagon that was attached to a tractor. Their condition had deteriorated drastically and one of the female guards beat them with a truncheon for not alighting fast enough. Some crawled on all fours. Once on the wagon, the tractor drove via the yard where the marchers had slept and picked up another 15 women who could go no further. They were taken to Rehau and left there.

That same day, the remaining women marched 17 km from Schwarzenbach an der Saale, through Quellenreuth and Rehau, to Neuhausen. After some 4 km, one of the prisoners fell behind and Kowaliv, a guard, shot her near Quellenreuth. Her body was found later and buried where it was discovered. The day's second victim was a prisoner who was taken into the forest left of the road between Rehau and Asch, some 5 km after the march had passed through Rehau. She was shot there, and close by, on the right, another prisoner was shot. Further along the route, two more prisoners from Hungary – 29-year-old Aranka Brody and 17-year-old Elsa Habermann – were shot 40-50 meters apart. The bodies of all four women were found by the Americans, who reached the area on 9 May. They were buried in a mass grave in Rehau.

The same day or the following day, 24-year-old Basha Wechsler of Dąbrowa Górnica, Poland, was shot. Basha was being supported by her friend Anny Keller (Hanah Kotlicki). Inge Schimming, a female guard, pulled Basha away from her friend and dragged her into the forest. Schimming returned alone.

The marchers reached Neuhausen, situated on the mountainous border between Germany and Czechoslovakia (the Sudetenland). The prisoners didn't receive any food that day, and they slept outdoors.

A messenger from the SS arrived in Neuhausen and informed Alois Dörr, commander of the march, that he was under orders to stop shooting prisoners and to release them as the Americans were approaching. The guards were also ordered to stop shooting and harming the prisoners. Dörr ignored the order.

That evening, Dörr was notified that the Americans were 15 km away from Neuhausen. He was told that negotiations with the Allies were taking place, and was ordered to destroy all documentation. He gave the order to burn documentation, and decided to continue the march immediately. In the ensuing chaos caused by the nocturnal departure, some 50 prisoners from the group of non-Jewish women that had left Helmbrechts, escaped. In addition, some of the female guards seized the opportunity to escape under cover of darkness.

Days 86-95 of the Death March, 730 km From the Start of the March

Between Zwodau and Wilkenau: Strafing of the Women in the Wagons

On 17 April, the marchers reached the Zwodau camp, where they met the sick prisoners whom had been sent there from Ölsniz by Karl Herman Jäschke, commander of the first section of the march. Of the 160 sick women who had arrived at Zwodau, 37 perished by the time the camp was evacuated. The marchers also met the sick women who had been sent on the truck from Schwarzenbach to Rehau, and from there to Zwodau. Some 150 Jewish female prisoners who had been transferred there from other camps even before the group from Helmbrechts had arrived, were also incarcerated in the camp. At Zwodau, Dörr was given orders to leave all the non-Jewish prisoners he had brought from Helmbrechts and to take with him only the German women and the Jewish prisoners, some 800 in number. The Jewish women were sick, emaciated and extremely weak. After a day's rest in Zwodau, the women left the camp.

After a week, during which time they marched more than 70 km, they reached Neustadt in the pouring rain on the afternoon of 23 April.

The next day, on the morning of 24 April, the women left Neustadt, and after 22 km, the marchers reached the village of Wilkenau in the afternoon. Those who were too weak and sick to walk were carried on horse-drawn wagons, escorted by guards and retreating German soldiers. Near Ronsperg, the column was strafed by low-flying US aircraft. Several prisoners were wounded and killed. Some soldiers took the wounded Netka Demska to the local military hospital and later, one of the guards brought her back to the march. Netka survived. Another young woman, Sonya Federman, was also wounded in the bombardment. One of the guards wouldn't allow her to be treated for her wounds, saying: "There are no hospitals for Jews. Jews don't deserve to be helped."

Several horses were also killed in the bombardment. The ravenous prisoners swooped down on the dead horses, tearing the raw meat and fat with their bare hands and devouring it. During the strafing, Mary Reichmann (Robinson), who was in a very weakened state, fell from the wagon she was traveling on. Her friend Lola Lehrer brought her some horse liver to eat, and Mary is convinced that this saved her life.

Some of the prisoners took advantage of the chaos engendered by the strafing to escape. In Wilkenau, the marchers were put up in farmers' granaries. In one of the farm courtyards, prisoners found a heap of rotting fodder unfit for animal consumption. Some of the starving women ran to the fodder and began to eat. One of the guards shot a prisoner and wounded her in the leg. He then drew closer and shot her in the head.

That day, the prisoners received a portion of soup, prepared for them by the residents of Wilkenau on the orders of the guards.

The same night, at least 9 women perished. They were buried together with the prisoner who had been shot.

The 96th Day of the Death March, 750 km From the Start of the March

Wednesday, 25 April 1945

Day 96 of the March: Assistance Attempt by Residents of Taus (Domažlice)

For many days, the marchers were not given food or drink. On "good" days, they slept in granaries along the way, but on many nights, they slept on the snow in the open field where they stopped for the night. Each day, their numbers diminished. Every morning, the women found the bodies of those who had perished in the night, finally defeated by exhaustion, starvation and cold.

On 25 April, the prisoners left Wilkenau. After they had marched some 1.5 km, a guard shot one of them in the chest near Neugramatin, and left her where she lay.

That day, the women crossed the border between the Sudetenland and the Protectorate of Bohemia-Moravia (today part of the Czech Republic), and reached the city of Taus (today the Czech city of Domažlice). The locals tried to give the prisoners food and drink, and were openly hostile towards the German guards, who tried to disperse them by shooting into the air. Some of the women took advantage of the situation and escaped. Further along the way, the Czech residents of the village of Mraken tried to feed the marching prisoners. Dörr became careful to avoid the main roads and to veer the march towards Sudeten settlements that had been evacuated of their Czech inhabitants, leaving only Germans.

At the end of the day, after marching some 20 km, they reached Maxberg. Dörr demanded that the Mayor find lodging for all the prisoners. The Mayor explained that there was no granary large enough to contain them all, and suggested housing them in several different locations. Dörr decided that the women would spend the night outdoors. The locals prepared soup for them. During the distribution of the soup, the ravenous women pushed and shoved, resulting in the halt of the distribution. That night and the next morning, the prisoners didn't receive anything to eat. At least 3 women perished during the night.

The 104th Day of the Death March, 875 km From the Start of the March

Six Days Before the War's End

The Last Days of the Death March; Arrival in Volary

On 3 May 1945, 325 Jewish prisoners and 25 German prisoners reached Volary. The group that had marched on foot arrived in the evening, and the sick women brought on wagons arrived later that night. The residents of Volary tried to give the women food, but the guards prevented them from doing so. One of the female guards beat the prisoners who stretched out their hands for food.

Dörr had decided to let the remaining prisoners go. He planned to take them to the neighboring city of Prachatice, on the border between the Protectorate (Czechoslovakia) and Germany, and to release them there. On the afternoon of 4 May, the Jewish women underwent a selection at the hands of Dörr. 150 Jewish women and the 25 Germans continued the march on foot. The remaining 175 were categorized as unfit to walk. 35 of them were hauled up onto vehicles driven by Dörr and some of the guards, the intention being to rustle up more vehicles to bring the rest of the women to Prachatice.

5-6 km northeast of Volary, the vehicles were strafed by a low-flying American aircraft, but the prisoners were not wounded. One of the guards, Ruth Schultz, who was pregnant, was killed on the spot, and two more were injured. Some of the prisoners took advantage of the situation to escape, but most of the women in the vehicles were too weak, and the guards locked them up in a granary in the town of Bierbruck.

Not far from the granary, 3 guards caught 12 women from the group who were walking, stood them against a wall and shot them. Their bodies were left where they lay. The guards were eager to avenge the death of Ruth Schultz and the injuries of the other guards, and were angry that the Jewish women had not been hurt. It would seem that one of the guards was Schultz's boyfriend, and the father of her unborn child.

The group of marchers continued via Pfefferschlag towards Prachatice. Close to Prachatice, a guard shot one of the women in the head. Her body was found after the Americans arrived, and she was buried in the cemetery in Prachatice.

The marching women reached Prachatice at night, and charge of them was transferred to the local home guard, the Heimwehr. The 25 German prisoners were released.

In the shack of a furniture factory in Volary, 140 women lay dying. The two guards that had been left in charge of them waited in vain for the vehicles to return from Prachatice and to collect them together with the prisoners. That night, the two guards left.

The 106th Day of the Death March, 890 km From the Start of the March

The Last Day of the Death March

On the morning of 5 May, 3 guards evicted all but one of the women from the granary in Bierbruck where they had been locked up. The remaining prisoner, Lola Lehrer, had managed to hide, and was later found by the farm owner, who took care of her.

For about half an hour, the guards forced them to run up the mountain and into the adjacent forest. 19 of the 22 women were shot, and their bodies were left in the forest. Eventually, the guards released the last three women who were still alive. All three – Anny Fogel, Luba Federman (Dzilovski) and Jadzia Goldblum - survived.

Some of the women who had carried on marching to Prachatice managed to escape. The remainder was handed over by Alois Dörr to the local home guard, the Heimwehr, that brought them to a hill in a forest. The women feared that they were about to be executed, but their guards, who were mostly older men, ordered them to sit in an open field, and that night they abandoned them. Only the next morning, Sunday, 6 May 1945, did the women realize that they were unguarded. They descended the mountain in an easterly direction, towards the rising sun – the direction of the Russians. Most of them reached Husinec, a Czech village in the territory of the Protectorate. They arrived when the villagers were in church. A local pharmacist, Vaclaw Plachta, saw one of the women and alerted the church-goers. They brought them to the local tavern. The village's only doctor, Dr. František Krejsa, took care of them. On his instruction, the villagers brought soft food from their homes. The doctor telephoned the mayor of the neighboring city of Vodňany, and requested his assistance. The women were housed in the local school in Vodňany, which became an improvised hospital. 12 women suffering from typhus were transferred to the hospital in nearby Volyně, where two of them – Masha Heide and Liwia Zaks – died.

Meanwhile, the residents of Volary, headed by Oskar Knöbl, started to administer treatment to the sick women who had been left in the shack.

"From my knowledge of world history, never has the world witnessed such mass bestially and brutality as was evidenced in the treatment of these women."

Major Henry N. Hooper, Volary, 8 May 1945

Liberation

On 6 May 1945, the US Army's 2nd Regiment of the 5th Infantry Division, entered Volary. After the residents reported that there was a group of young, sick Jewish women in the shack of the furniture factory, they sent some men to the shack. 20 women perished before the Americans arrived, and two more on the day that they came. There were 118 surviving women in the shack, most of them in dire condition. Gerda Weissmann Klein describes the day that the Americans entered Volary in her memoir "All But My Life":

Liesel was lying on the littered floor. She knew we were free but did not seem elated. "Where is Suse?" I asked her... "She went out to get water and hasn't returned. She has been gone a long time"… I went out to look for Suse. She was not at the pump. I found her off a way lying in the mud. Her eyes were glassy, unseeing, but for a moment I did not realized she was dead… "Suse, we are free!" I called to her. "We are free, the war is over!'… When I touched her, I knew the truth… I did not tell Liesel. It was too sad for liberation day.

Four days later, on 10 May, Liesel Stepper also perished in the hospital in Volary.

On 8 May 1945, two days after they had arrived at the shack in Volary, the Americans opened a comprehensive investigation in order to establish what these women had endured, and how they had come to be in the deplorable state in which they were found. During the investigation, testimonies were gathered from some of the survivors of the march, and from some of the SS women who had accompanied the march, and who were later caught. The investigation was headed by Lieutenant-Colonel Robert F. Bates, of the 5th Infantry Division. As well as the testimonies, the resulting report contains shocking photographs of the survivors after their arrival in Volary, and details of their medical conditions.

-

US Army veteran Harry Mogan recalls about his first encounter with Nazi atrocities

-

US Army veteran Kurt Klein talks about a US Army officer's first encounter with Nazi atrocities

-

US Army veteran David Olds talks about his first encounter with Nazi atrocities, and with the German residents of Volary

"...when I entered the room I thought that we had a group of old men lying… at that time judged their ages ranged between fifty and sixty years. I was surprised and shocked when I asked one of these girls how old she was and she said seventeen, when to me she appeared to be no less than fifty...

Major Aaron S. Cahan, (US medical officer), Volary, May 7th 1945

The Hospital in Volary

The German military hospital in Volary was situated in a 4-storey school building. On 7 May 1945, the 118 women were transferred from the shack of the furniture factory in Volary to the first two floors of the hospital, after the wounded German soldiers there were evicted.

They were in dire condition. Most of them weighed between 30-40 kg. 111 of them were suffering from malnutrition and severe vitamin deficiency. Many had dysentery. Almost all were riddled with lice. The soles of their feet were swollen, scarred and ulcerated. Some 20 of them had frostbite.

Major Aaron S. Cahan, a US medical officer, was appointed to check on the women, to supervise their transfer to the hospital, and to oversee their care. He arrived at the shack of the furniture factory in Volary on the afternoon of 7 May. In the testimony he gave two days later he relates:

My first glance at these individuals was one of extreme shock not ever believing that a human being can be degraded, can be starved, can be so skinny and even live under such circumstances... like mice on top of one another too weak to as much as raise an arm… when I entered the room I thought that we had a group of old men lying… at that time judged their ages ranged between fifty and sixty years. I was surprised and shocked when I asked one of these girls how old she was and she said seventeen, when to me she appeared to be no less than fifty… about seventy-five percent had to be carried in by litters. The other twenty-five percent were able with the help of others to drag their weary bodies from the shack to the ambulance… As a medical officer of the United States it is my opinion that at least fifty percent of these 118 women would have died within twenty-four hours were they not located and given the best of care.

Despite the care they were given, 19 more women perished in the hospital, among them 25-year-old Fela Szeps of Dąbrowa Górnicza, Poland. Fela weighed 29 kg at her death. According to her medical records, she looked like a 75-year-old woman. Fela perished in the hospital in Volary on 9 May. The photograph of her dying on the wooden plank bed was distributed amongst the 2nd Regiment of the 5th Infantry Division.

A few days later, on 13 May, 17-year-old Nadja Rypsztajn of Lodz, Poland also perished. Nadja and her three sisters, Fela Eisen, Guccia and Mina had all marched together from Schlesiersee. Guccia and Fela were murdered along the way. Only Mina (Heller) survived.

In November 1945, 17-year-old Dora Ebbe of Wiesbaden, Germany, perished. She was the youngest of four sisters who started out on the march together from Grünberg. Her sisters, Hanni, Nellie and Leah, buried her in the cemetery in Volary and left only after the shiva (seven days of mourning).

Most of the survivors that recuperated left Volary in July 1945, and made their way to the DP camps.

The Americans established a cemetery for victims of the march in Volary. Accompanied by some of the survivors, they retraced the steps of the women, as far as was possible within the time constraints, and buried the women who had perished along the way.

There are 95 graves in the cemetery in Volary.

The residents of Volary have tended the graves from the end of the war to this day.

The Perpetrators

Alois Dörr, commander of the Death March from Helmbrechts to Volary, was put on trial in 1969 in the court of Hof, Germany. For his crimes, and the crimes of those under his command, he was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. After 10 years in prison, he was released on grounds of poor health. Dörr died in 1991.

Karl Herman Jäschke, commander of the Death March from Schlesiersee to Helmbrechts, was incarcerated in a Polish prison in 1947 for war crimes. He was released three years later, and died in 1970.

In 1995, the legal authorities in Hof, Germany commenced the preparation of an indictment against Inge Schimming (Asmus), one of the SS women who escorted the march. Asmus died in Berlin before she was brought to trial.

-

Holocaust survivor Gerda Klein recalls the first time she met US Army officer Kurt Klein, later to become her husband, in the shack in Volary

-

Holocaust survivor Suzy Raful recalls meeting American soldier Robert-Bob Raful, later to become her husband, in Volary

-

US Army veteran Kurt Klein recalls the first time he met survivor Gerda Weismann, later to become his wife, in the shack in Volary

They took everything from us, and nothing can heal the wound... we're scarred for life...

Hanah Kotlicki

Coping with Loss and Return to Life

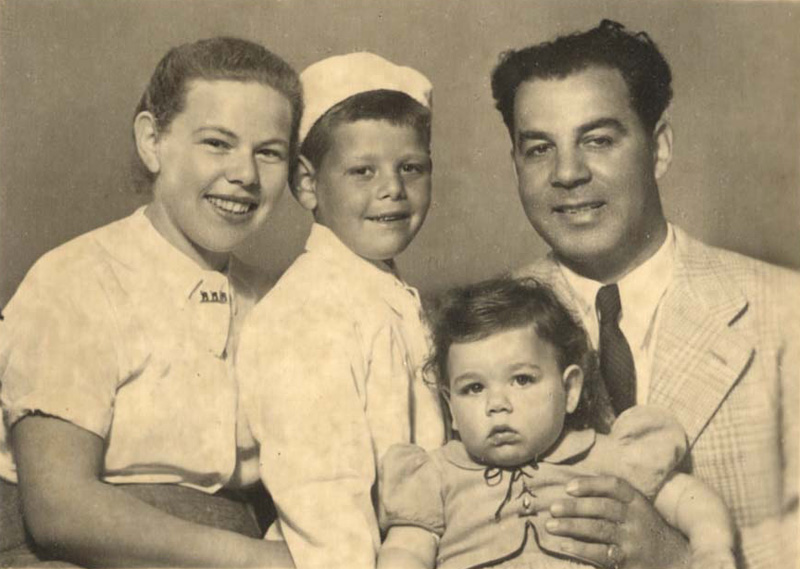

After a period of recuperation, most of the death march survivors left Volary in July 1945.

Some returned home in the hope of locating surviving family members, but only very few found anyone. Most of the women reached the Displaced Persons camps situated in Austria, Germany and Italy. There, they began the slow and painful process of rebuilding their lives, while coping with their grief, the trauma of the war years, and the loss of their loved ones.

After a time, most of the women left Europe and immigrated to other countries, principally Eretz Israel and the US. Once there, the search for work and the inevitable language barriers brought new challenges. They got married, started families and became involved in community life. Family was their highest priority, and they found joy and fulfillment in being able to give their annihilated families new life.

USA, 1955