Expanding on last week’s entry regarding the day-long symposium on May 6, 2013, which discussed performing arts in Holland during the Holocaust and was sponsored by the International Institute for Holocaust Research at Yad Vashem along with the International Institute for Jewish and Israeli Culture, the following post will shed additional insight concerning the continual use of theater in an increasingly terrible period following the deportation of Dutch Jewry and their internment in camps. Beginning in the summer of 1942, the Jewish Theater was dissolved as a cultural forum and began to be used by the Nazis as an assembly point to begin the mass deportations of Dutch Jewry, taking them by train to the concentration and transit camps: Westerbork and Vught.

Part 1: https://www.yadvashem.org/blog/theater-in-holland-a-cultural-refuge-during-the-holocaust-part-1

Located in the northeastern part of the Netherlands, Westerbork, the larger of the two camps, was initially established before the Nazi occupation by the Dutch government in 1939 to detain German Jews who fled the Nazi regime and entered the country illegally. Following the occupation of the Netherlands by Nazi Germany, Westerbork became a concentration and transit camp used to gather and deport Jews to other Nazi extermination and concentration camps such as Auschwitz, Sobibor, Theresienstadt, and Bergen-Belsen. Among those concentrated in Westerbork were many of the talented Jewish performing artists living in Holland at the time who were taken to the camp temporarily before eventually being sent to one of the various Nazi camps in Europe mentioned above.

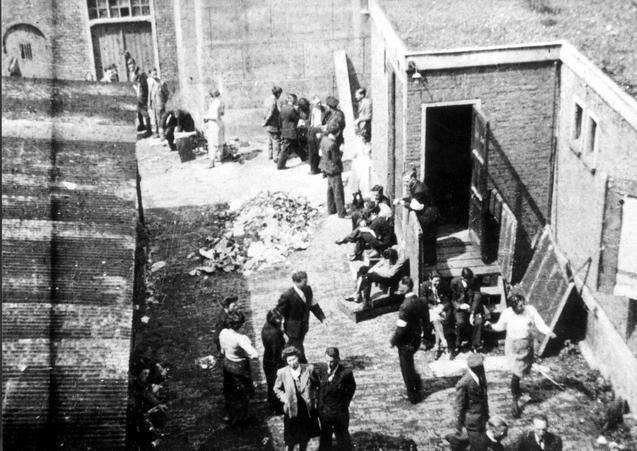

On October 12, 1942 SS-Obersturmfuehrer Albert Konrad Gemmeker was put in charge of the camp, overseeing and carrying out the orders from the office of Adolf Eichmann concerning the timing, extent and destination of the mass deportations. The way in which the Nazis administered Westerbork was unusual in that it tried to give the Jews deported there a false sense of normality and a feeling that through obedience they would be decently treated. This was done for a number of reasons including providing a cover that would aid the level of ease, compliance and control in deporting the inmates to their deaths in extermination camps in the East as well as assist Nazi propaganda purposes in portraying the conditions within the camps as “humane”. However, perhaps one of the strangest and most distinctive occurrences at Westerbork, which characterized the German deception regarding the camp’s ultimate purpose, was Gemmeker’s decision to allow many of the renowned Jewish performing artists imprisoned in the camp to put on elaborate theatrical productions. Such extensive encouragement by the Nazi camp commander in allowing Jewish prisoners to partake in cultural activities such as theater made Westerbork stand out as a rare outlet for the performing arts during the Holocaust.

The “Camp Westerbork Theater Group” was established under the direction of Max Erlich, a famous German-Jewish actor, writer and director imprisoned at the camp, who led the company in putting on a number of original full-scale theatrical and cabaret productions in addition to a weekly performance. At its height the theater group had over 50 performers including well-known Jewish German and Dutch artists such as Willy Rosen, Erich Ziegler, Franz Engel, Kurt Geron, Esther Philipse, Jetty Cantor, Camila Spira and Johnny & Jones. For many camp inmates, the Westerbork theater was a temporary distraction and cultural refuge from the devastating reality that, at any time, one could be deported East to a far worse fate. Since there was no telling how long one would be kept at Westerbork before being put on a list for deportation (ranging from a week to over a year), to a large extent the theater was permitted as it provided an element of control over the camp’s population. By having a performance the evening before a forced deportation to an extermination camp, the Nazis used the medium of art that is theater to maintain a sense of calm among the camp’s Jewish prisoners during a period of great turmoil and tension. Nevertheless, for many at Westerbork the theater provided an artistic escape from the daily forced labor and the grim realization that one could be sent on a train to a more terrible place. While the theater did prolong the time at Westerbork for its many famous and talented performers, it only delayed those Jewish artists, such as Erlich, Rosen, Engel, Geron, Philipse and Johnny & Jones, from the same horrible fate suffered by the almost 100,000 Jews detained in the camp who were sent to their untimely deaths at the hands of the Nazis and their collaborators. For most of those detained at the camp who would ultimately fall victim to Nazi cruelty, a performance at Westerbork would be their last.