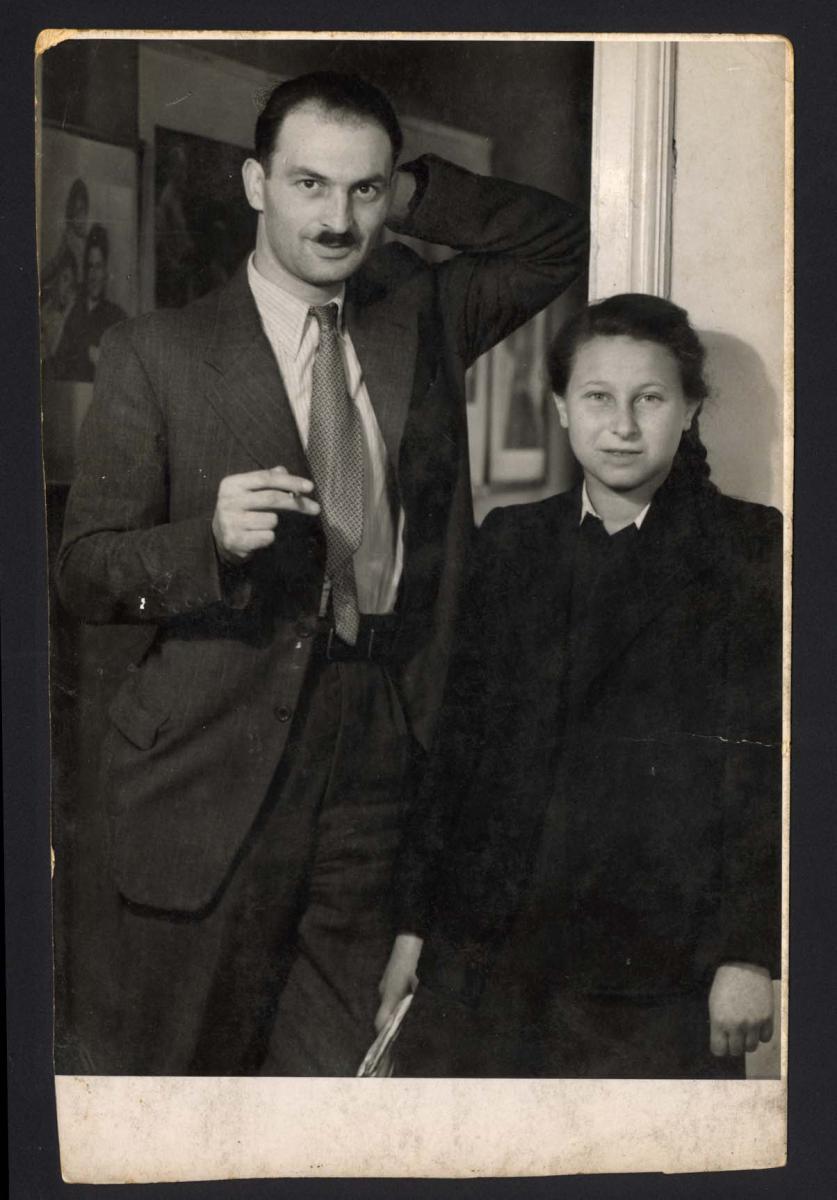

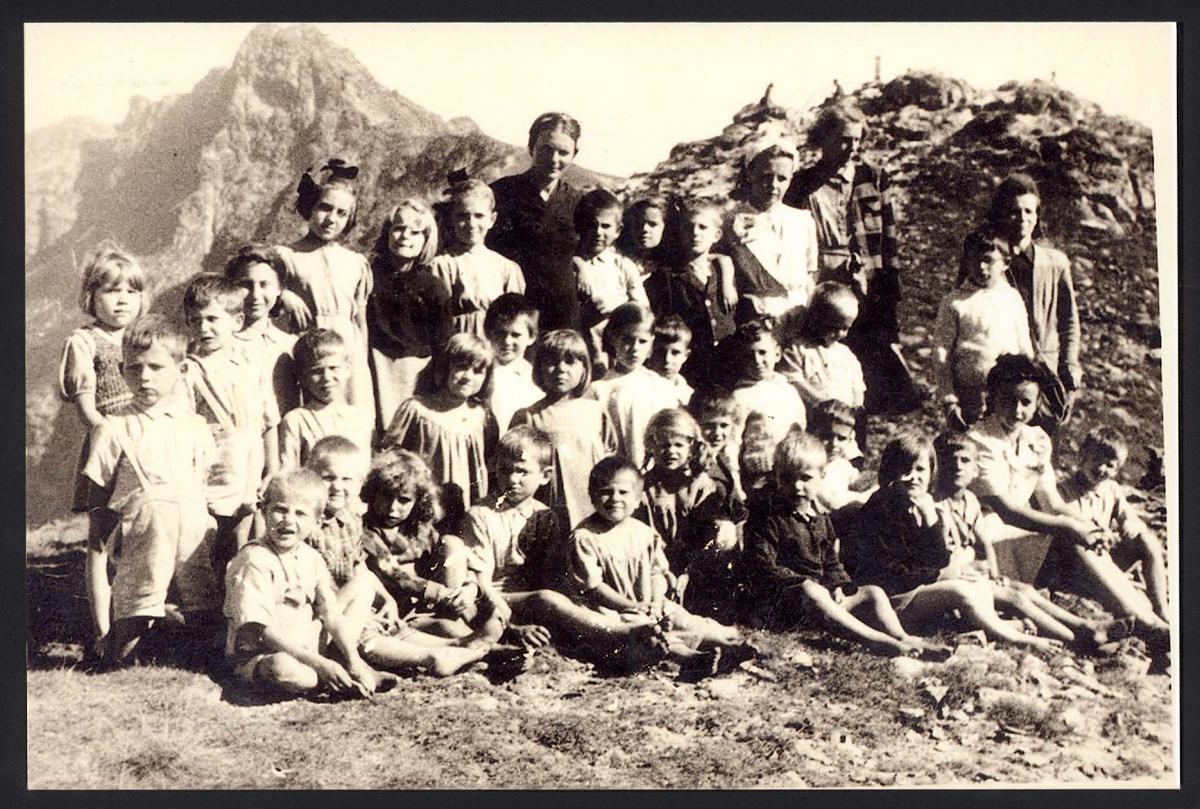

Private Collection of Janina Hescheles-Altman, Haifa Israel/Yad Vashem

Private Collection of Janina Hescheles-Altman, Haifa Israel/Yad Vashem

Private Collection of Janina Hescheles-Altman, Haifa Israel/Yad Vashem

Private Collection of Janina Hescheles-Altman, Haifa Israel/Yad Vashem

Private Collection of Janina Hescheles-Altman, Haifa Israel/Yad Vashem

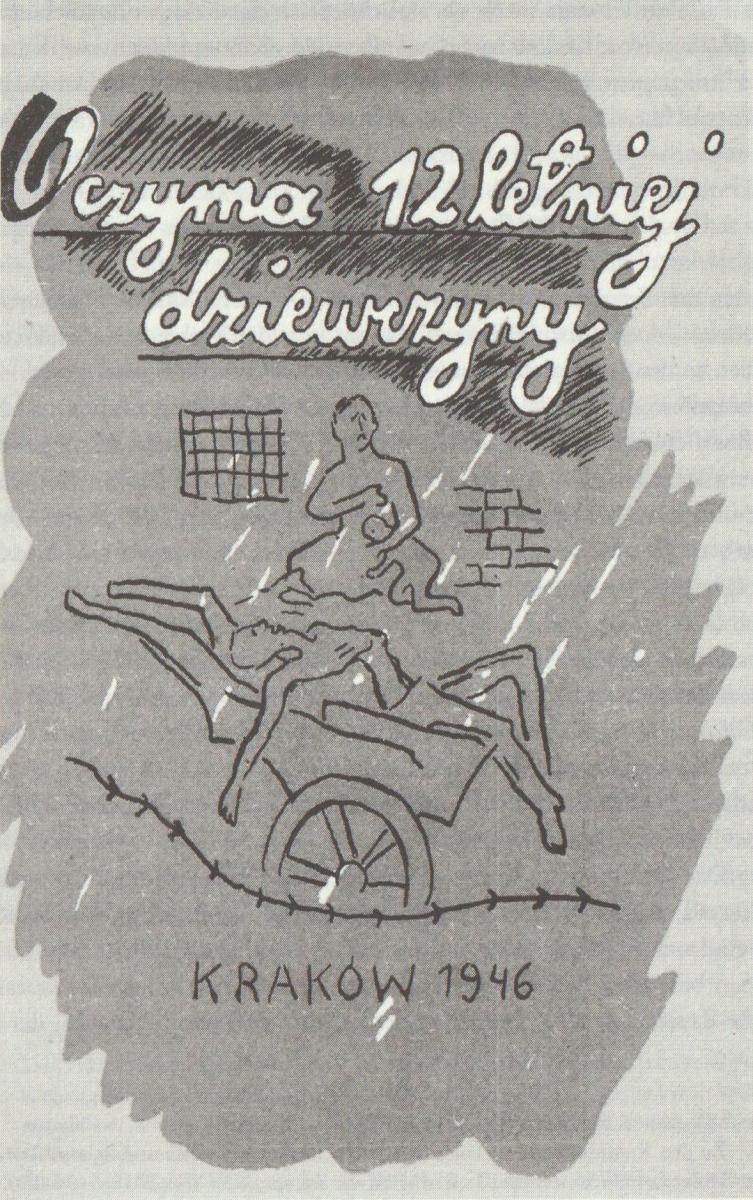

Yad Vashem

On Sunday, 24 July 2022, Holocaust survivor Dr. Janina Altman (née Hescheles) passed away. Janina's life story is displayed in Yad Vashem’s Holocaust History Museum in the chapter dealing with Żegota – the Council for Aid to Jews that was active in Nazi-occupied Poland. At the age of twelve, Janina wrote a diary while in hiding in Krakow.

Janina was born on 2 January 1931 in Lvov, Poland (now Ukraine), the only child of Emilia and Henryk Hescheles. Henryk was the chief editor of the Jewish newspaper Chevila (Moment) and Emilia was a Hebrew teacher and nurse. Janina wrote in her diary about the invasion of Lvov by the Germans in the summer of 1941:

“My father kissed me and said: ‘Janio, you are already ten years old and you need to be independent. Do not rely on acquaintances. Always be brave.’ He hugged me and turned to separate from me. I began to understand what was going on, and my mouth began to quiver. I was ready to burst into tears, but my father told me: ‘If you truly love me, walk with courage and never cry; crying is humiliation in times of calamity as well as in times of happiness. Go home now, and leave me here.’ I kissed my father for the last time and left… this is how we separated forever.”

In a three-day pogrom at that time, some 4,000 Jews were murdered by the Ukrainians, including Henryk Hescheles.

Janina and her mother were imprisoned in the Lvov ghetto, where many of their relatives were murdered. On the eve of the ghetto’s liquidation, Janina was separated from her mother. Emilia was deported to the Janowska concentration camp. Janina managed to escape from the ghetto and made her way to Janowska, where she discovered that Emilia had committed suicide together with the rest of the medical team. Janina was now alone.

In Janowska, Janina wrote many poems, which she recited to the prisoners in her barracks. Among other works, she wrote the poem “Belzec”:

“What a horrible sight

A train car full of people

In the corner a number of bodies

Everyone standing naked

Their moans deafening the whirring of the wheels

Only the one condemned to death understands

What the wheels says about him:

To Belzec! To Belzec! To Belzec!

To Death! To Death! To Death!

If you want to live…

Jump! Run! Run!

But be careful

Because a guard is also waiting for you.”

Janina’s poems drew the attention in particular of another camp prisoner, the Jewish author Michal Borwicz, who became her friend. When Borwicz later escaped the camp with the help of Żegota, he demanded the escape of another group of prisoners, including Janina Hescheles. The group escaped with the assistance of Żegota’s courier, Ziuta Rysinska.

In October 1943, Janina was transferred into the care of Miriam (Marianska) Hochberg, a Jew working for Żegota in Krakow. Marianska arranged her hiding place, and three weeks later brought her a grey notebook and told her to write. Marianska later wrote about this in her book Witnesses: Life in Occupied Krakow.

“We began vigorously searching for a hiding place for the young Janka Hescheles, who had escaped from Janowska. I contacted Wanda Janowska [later recognized as Righteous Among the Nations] about this and she decided without hesitation to take this young protégée into her apartment. Here in her first shelter, Janka began writing her diary…. But Janka did not find peace in Wanda’s home for long. One day, Wanda was warned that a Jew who had Wanda’s address listed on her documents had been discovered, and it was expected that Wanda’s home would be searched at any moment. We had to immediately remove the false identity papers from the workshop and Janka Hescheles from the apartment.”

Janina lived in several other hiding places until the fall of 1944, when Hochberg met Jadwiga Strzałecka, who had run an orphanage in Warsaw and, after the Polish Uprising, had moved with the children to Poronin, next to Zakopane. Hochberg wrote about the meeting between them in her memoir:

“Ten out of the forty children in her institution were Jewish. When I told her about Janka, she immediately said: ‘Please bring her to us, I am sure she will feel comfortable amongst our children.’ Her proposal was a blessing from Heaven, and Janka was given the opportunity to be freed from her nightmare for the last months of the war.”

Janina Hescheles’s diary was first published in Polish in 1946 by the Jewish Historical Commission in Krakow and was edited by Michal Borwicz. The three grey notebooks in which Janina wrote in large, round, childish script were housed in Borwicz's personal archive, until he transferred them to the Ghetto Fighters' House Museum. Since then, the diary has been published in many languages. In 2016 it was finally released in Hebrew, translated by Janina herself, and in 2020 it was published in English as My Lvov: Holocaust Memoir of a Twelve-Year-Old Girl.

In 1950, Janina immigrated to Israel, and in 1953 she was accepted to study Chemistry at the Technion in Haifa. A decade later, she completed her doctorate in that field. She worked in research at the Technion, at the Weizmann Institute for Science, at the University of Dusseldorf, and in Munich, Germany. She married a physicist, Prof. Kalman Altman z”l, and they had two sons, Tzvika and Eitan. Among her many writings, she published a book about the White Rose underground movement: students and intellectuals in Germany who were active before and after Hitler came to power. May her memory be for a blessing.