Bratislava Before the Holocaust

Until the End of the First World War

The Beginnings of the Bratislava Community

The presence of Jews in Bratislava is first mentioned during in the 13th century, but it seems that a Jewish community in this location predates the documentary evidence. The Jews of Bratislava earned their living primarily from trade and financial dealings; some Jews were also artisans, and there is mention of Jews working as vine-growers and producing wine. In the 14th century the community numbered several hundred people. In 1360 the Jews of the city were expelled, and their property was stolen and destroyed. In 1368 several families were allowed to return and purchase spacious houses in the center of the city, in an area designated as the 'Jewish Square' (Judenhof). However, the authorities continued to persecute the Jews, imposing on them various taxes and other restrictions, including the 'Jewish Book', which regulated financial transactions between Jews and non-Jews. In 1399 the Jewish community obtained permission to build a synagogue, apparently in place of a former synagogue which had been destroyed when they were expelled. During the first half of the 15th century the Jews lived in a kind of ghetto on the 'Jewish Street' and were forced to wear special clothing known as 'Jewish clothing'. Yet despite the adverse circumstances, the community grew and even obtained permission to build a second synagogue.

In 1526 the Jews of Bratislava were again expelled from the city. The synagogue was destroyed and a monastery built in its place. Most of the Jewish expellees fled across the Danube to Austria, but a minority settled on the Schlossberg (literally: the Fortress Hill), at the foot of the fortress outside of the city. In 1572 Emperor Maximilian forbade Jews from living on the Schlossberg and most of them departed.

In 1599 the fortress on the Schlossberg was inherited by the Palffy family, and Jews were allowed to return to two quarters of the fortress area – Schlossberg and Zuckermandel. In 1670, when the Jews of Vienna were expelled, Jewish refugees found sanctuary in the Schlossberg quarter. In 1707 Count Palffy protected some 200 Jewish families, most of whom were refugees. Discriminated against by the local merchants, many Jews had to find sources of income beyond city and state boundaries. Taxes imposed on the local Jews brought the community to the brink of bankruptcy, and local merchants continued harassing the Jews.

At the end of the 18th century the restrictions on Jewish residency in Bratislava were gradually lifted. Hundreds of Jews took shelter behind its walls, and by the beginning of the 19th century there were more than 2,000 Jews living in the city. Centers for Jewish learning were established, attracting famous rabbis. Between 1806 and 1839 Rabbi Moses Sofer (Schreiber) - also known as the Chatam Sofer - was Bratislava’s chief rabbi. In the pogroms which took place in the shadows of the 1848-1849 revolution, the Jews of Bratislava were attacked and their property was looted and destroyed.

In 1864 an ornate synagogue with hundreds of seats was built on Zámocká Street. A group of liberal intellectuals founded a primary school in the spirit of the enlightenment and were met with opposition from the community’s rabbi, Rabbi Abraham Sofer, the son of the Chatam Sofer. Following the General Jewish Congress of Budapest (1868/1869), which was attended also by delegates of the Jewish community in Bratislava, a split developed within the Jewish community of Bratislava. Most of the Jews – between 900 and 1000 families – belonged to the Orthodox community, while some 60 families belonged to the Neolog community. Both communities existed side by side until the onset of the Holocaust. In 1897 Ahavat Zion was formed - the first Zionist group active in the city.

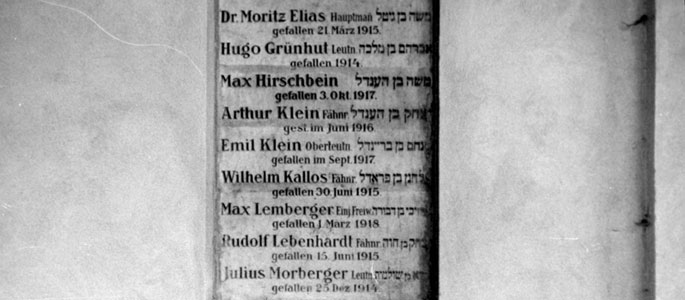

From the beginning of the 20th century the social and financial situation of the Jews of Bratislava began to improve. Many of them attended university and acquired training in the liberal professions, and some Jews attained leading positions in the civil administration. In the 1900 elections, 24 Jews were elected to the city council. Jews made their mark in the commercial life of the city and the greater metropolitan region. In 1910 there were 8,027 Jews living in the city. During the First World War hundreds of Jews from Bratislava were drafted into the Austro-Hungarian Army; some 50 of them fell in battle.

Government of the Federal Republic of Germany