Bratislava During the Holocaust

Under Slovakian Rule

Every day the authorities pass new laws aimed at limiting the freedom of Jews and isolating them from the non-Jewish environment, which is now called “Aryan”… Yet inwardly life is as spiritually vital and full as in the past. Crowds still gather in the synagogues and the study halls in the Jewish quarter, although this activity is now fraught with danger. Oskar (Yirmiyahu) Neumann

In March 1938, following the annexation of Austria into the German Reich, hundreds of Jewish refugees arrived in Bratislava, most of them from Germany and Austria. The Jews of the city took them into their care, while the refugees were awaiting their emigration to Eretz Israel. Later on, Jewish refugees from Czech territories also found refuge in the city.

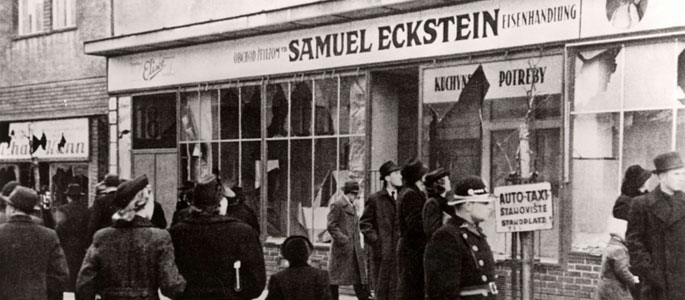

In October 1938, after Slovakia had been granted autonomy, Slovak nationalists and pro-Nazi German youth began reprisals against the Jews of Bratislava. They broke into the synagogue and other public institutions, smashing windows, destroying property and attacking Jewish passersby, many of whom required subsequent medical treatment. In November 1938 dozens of Jewish families without Slovakian citizenship were deported across the border into the no-man’s-land between Slovakia and Hungary. The civil authorities confiscated their property and handed their apartments over to the non-Jewish residents of the city. The Jewish community in Bratislava assisted the deportees by providing them with food and warm clothes. After some time, following pressure from the community and international organizations, some of the deportees were allowed to return; the rest were transferred to Hungary. At this time the Jewish members of the city council were dismissed, and the Jewish-National Party was outlawed.

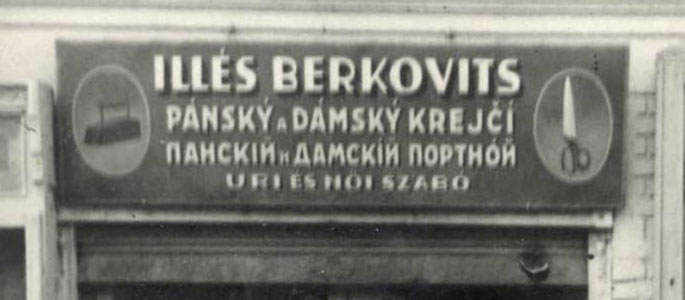

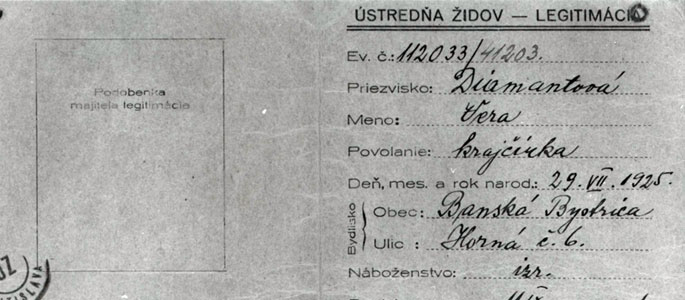

In March 1939 the independent state of Slovakia was created, a puppet state of Nazi Germany, headed by President Jozef Tiso and Prime Minster Vojtech Tuka. The situation of the Jews worsened. Bratislava became the capital of Slovakia, and the seat of the governmental and public institutions. The Jews of Bratislava were the first of the Slovakian Jews to endure humiliations, persecutions and financial restrictions. At the end of 1939 the licenses of most of the Jewish doctors and lawyers were revoked and many Jewish public officials were fired. Jewish organizations and associations were banned, with the exception of the Jewish communities and their institutions. Many Jews were evicted from their apartments in central areas in the city, and the confiscated property was handed over to state and party supporters. Hundreds of families were forced to hurriedly abandon their apartments – they had to crowd together in the Jewish quarter, penniless and in bad conditions. The authorities in Bratislava ordained the creation of the Jewish Center (Ústredna Židov or ÚŽ). Jewish students were expelled from public schools, and forced to study in exclusively Jewish schools, a situation which continued until the beginning of the deportations to the extermination camps in Poland, in the spring of 1942.

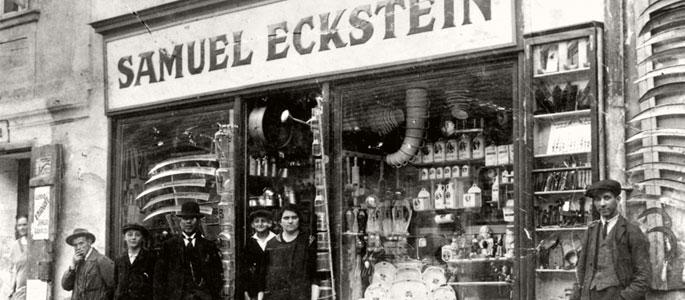

In the beginning of 1941 the authorities increased their effort to divest Jews of their property. Hundreds of Jewish stores and businesses were closed and handed over to Slovakian or German owners. Most of the city’s Jews remained unemployed. Some of them were recruited for forced labor, and hundreds of families found themselves in need of assistance from the community’s institutions.

Both Jewish communities in the city – the Orthodox community and the Neolog community – continued to operate as they had before. At the end of 1939 Rabbi Akiva Sofer retired from the office of chief rabbi, after 33 years, and together with a group of his students immigrated to Eretz Israel. His son, Rabbi Samuel Benjamin Sofer, was elected to lead the Orthodox community in his place; he also became the head of the Pressburg Yeshiva, which continued to operate despite a decline in its number of students. The yeshiva was finally closed in the summer of 1943.

In 1942, during the paving of a new road, a tunnel was dug under the old Jewish cemetery which subsequently collapsed and was desecrated. The human remains were reburied in a mass grave in the second Jewish cemetery, together with the broken tombstone shards. Only a small section of the old cemetery remained intact, containing the tomb of the Chatam Sofer, several rabbis and public figures of the community.

Government of the Federal Republic of Germany